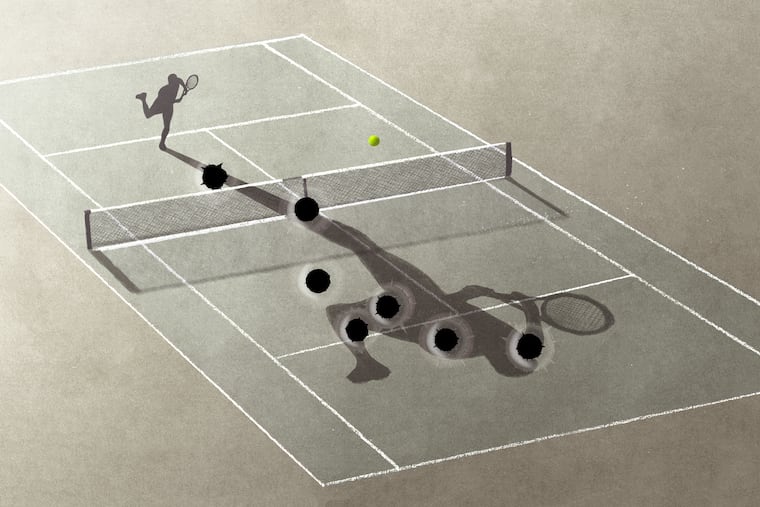

Gun violence lessons from my tennis instructor: The perfect shot is the one we don’t see

I find myself thinking about Ernest more in medical school than in the 11 years that have elapsed since his death.

When I was 12 years old, a message left on the answering machine of our landline informed me that Ernest Atiso, my tennis instructor, had been shot and killed from inside his car, his life exchanged for some money and a cell phone.

Ernest was the first instructor who saw something in me — or, better yet, taught me to see something in myself. With his gold-toothed smile and thick Ghanaian accent, he’d send me off to complete another set of laps around the tennis complex in the blazing heat of a New York summer, convinced of a fledgling strength in my scrawny prepubescent body with which I had not yet been acquainted. Any winner that I hit was met with a celebratory tap, tap, tap of his racquet against the ball basket, his dreadlocks dancing as he proclaimed me the queen of the court.

“When you’re convinced you’ve had enough, give more,” he’d say in earnest. And so, we tennis students would hurl our bodies down to the ground and then heave them back up to the sky, burpee after burpee, stretching the boundary on what we had to give.

For Ernest’s memorial service, several of his students were invited to play tennis in his honor, his casket lain across the court in place of the net. Thereafter the nets were raised, his body was sent to Ghana for burial, and my life wore on — high school, college, and now medical school at the University of Pennsylvania.

I find myself thinking about Ernest more in medical school than in the 11 years that have elapsed since his death.

I think of him when I saunter over to the Penn tennis courts to take a break from studying with my new classmates, when I hit a sweeping clean shot, when I feel strong in my body and its abilities, when my friends clap their hands against their racquets to signal applause.

I think of him when my friends and I, eating frozen yogurt in our neighborhood square in Graduate Hospital, are too frequently startled by a loud noise, our eyes betraying the question: “Gunshots or fireworks?”

» READ MORE: ER doc: America is bleeding out, and Philly is ground zero

I think of Ernest the most when I watch a man my age wheeled into the trauma bay at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, his body speckled with gunshots. I think of him when I stand on a step stool in the operating room and peer over the many surgeons’ hands that adeptly sew a patchwork quilt out of the man’s insides; when I watch his brain herniate into a tiny puddle by my shoe; when his life slips through his steadily slackening grip, his radial pulse whimpering for just a moment longer; when his body is convinced that it has had enough, and the room woefully accepts that there was truly nothing left to give.

I wonder, too, if Ernest had been rushed to a hospital, how many bags of blood were hung, when he was pronounced, if he knew he was dying. I wonder who stood in his OR and thought of someone they knew whose final moments may have followed a similar course.

In almost every level of biology class, starting with the introduction to the cell cycle in fifth grade all the way through to advanced electives in medical school, at some point the teacher asks students to raise their hands if they know of someone lost to cancer. And every time, many hands go up. For many of us, cancer is our driving force, one of the many reasons we went into medicine.

But there has been a revolution in cancer treatment, as more screening and emerging treatments have helped people live longer than ever before. While the fight against cancer continues, firearm violence has also stealthily assumed a growing, insidious centrality.

In coming years, a new question will be asked of American students seated in their biology classes: How many of you have lost someone to gun violence?

I recall how once, upon nailing a baseline forehand crosscourt winner when I was 16, I looked to my coach excitedly, expecting validation.

He shook his head in dissatisfaction. I slapped my arms down by my sides.

“But that was a perfect shot,” I whined, my growing fatigue accelerated by his disapproval.

“The perfect shot is the one you never needed to hit,” he started, “because you should have already won the point long before needing it. The point should have ended five shots ago. You should have put the ball away sooner.”

The perfect shot is the one we don’t see. It’s the ball that doesn’t need to be hit, the bullet that never exits its chamber, the gun that is put away and never used.

Ella Eisinger is a second-year medical student at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.