The quiet terror in American classrooms

In the months since the Trump administration lifted the so-called sensitive locations policy, the spaces where children learn and grow have lost their sense of safety.

There’s a certain hush that falls over a Philadelphia classroom when fear walks in — not loudly, but silently, like a shadow stretching across the floor. It’s the quiet dread of a child wondering, Will my mother, my brother, my father still be here when I get home?

That is not the kind of question a child should carry into school. And yet, in neighborhoods like Kensington and South Philadelphia, it is increasingly the question that defines an entire generation.

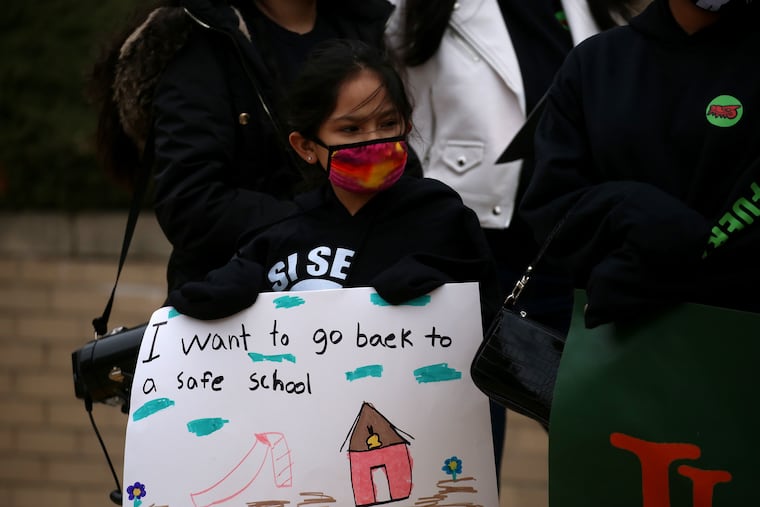

In the months since the Trump administration lifted the so-called sensitive locations policy — which once barred immigration enforcement from entering schools, churches, and hospitals — the spaces where children learn and grow have lost their sense of safety. The country’s great moral institutions — our classrooms, our sanctuaries, our hospitals — no longer feel like sanctuaries at all.

The Philadelphia School District has tried to respond. Since 2021, it has declared itself a “welcoming sanctuary district.” Staff are told not to share student information with federal agents, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is barred from entering without a warrant. The district even offers brief trainings and tool kits for teachers. Yet, the protection can feel thin. Some sessions, advocates say, last less than half an hour. Teachers are left with little practical guidance for the moment that truly matters — the knock on the door, the rumor in the hallway, the unmarked van outside.

Meanwhile, children live in a constant state of vigilance. They are learning to read and count and multiply in an atmosphere of uncertainty. They are learning not just how to speak up in class, but when it might be safer to stay silent.

There are more than 18 million children in immigrant families in this country, according to the Urban Institute — nearly one in four of all American children — and a large share of them live with this ever-present anxiety.

We like to imagine childhood as a time of curiosity and expansion, of trust in the world’s benevolence. But in too many corners of America, we’ve built a different reality — one defined by suspicion and fear. Immigration enforcement has become an unseen force shaping young lives, even for U.S. citizens whose parents are undocumented.

Under the first Trump administration, immigration policy shifted from an imperfect but humane management system to a tool of deterrence. More than 400 executive actions were taken to tighten, restrict, and punish. Deportation raids intensified in cities and suburbs alike. Families were separated. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was threatened.

As Jamie Longazel writes in the 2016 book, Undocumented Fears: Immigration and the Politics of Divide and Conquer in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, fear itself had become a policy. Although Hazleton has since become a town with a significant population of Trump-supporting Latinos, Longzel wrote about “the weaponization of anxiety,” a strategy designed not only to control immigrant populations, but to divide working-class Americans — immigrant and native-born alike — against each other. Longazel observed how fear narratives spread like wildfire, “turning neighbors into threats and compassion into weakness.” What began as a small-town battle over belonging became a national template for governance through division.

The emotional residue of those political choices lingers. In study after study, researchers have found that children in immigrant families who live under the threat of deportation exhibit higher levels of depression, chronic stress, and academic disengagement. A 2024 cohort study of Latinx youth, published by the American Medical Association, found that the fear of enforcement correlated strongly with anxiety and reduced school participation. These children live in what psychologists call “hypervigilant states”— their brains wired for survival, not learning.

Psychologists and other professionals who work with immigrant youth note that it’s difficult for children to learn a sense of trust when they grow up in homes where someone could be taken away at any moment. That sense of perpetual danger rewires a child’s brain, robbing them of the basic psychological safety necessary to thrive.

For many Black and Latino boys, the damage is compounded by the burdens they already carry: racial profiling, underresourced schools, and systemic inequities that punish rather than protect. Immigration enforcement adds another layer of trauma. The effect is cumulative. It narrows horizons and teaches young people that their citizenship, their worth, and even their right to safety are conditional.

Yet, these children are not broken. They are resilient in ways most of us can hardly fathom. But resilience is not a substitute for justice. We cannot continue to build a system that asks children to be brave in the face of our moral failures.

There are, thankfully, glimmers of a better path.

In Philadelphia and Boston, school districts are beginning to adopt trauma-informed and culturally responsive practices. Counselors are being trained to recognize immigration-related stress. Social workers are learning to navigate mixed-status family dynamics.

Organizations such as Juntos, in Philadelphia, and the Immigrant Family Defense Fund, in California, are helping schools fill the gaps left by policy neglect. These efforts, while small, represent a moral reawakening — a recognition that the harm done was not only procedural but human.

The damage was never just legal. It was emotional. It taught children that belonging is provisional, that safety is something they have to earn, that love of country might not be returned. This is what happens when a nation forgets that its greatness depends not on walls or warrants, but on the belief that every child deserves to feel safe enough to learn.

We often invoke the American dream as if it were a birthright. But dreams are fragile things. They depend on a culture of trust, on the faith that effort will be met with opportunity. And for millions of children growing up under the cloud of enforcement, that trust has been shattered.

The moral question before us is simple but profound: Can a society that terrifies its children still call itself good? Can a democracy built on fear still claim to be free?

If America is to remain a beacon of hope, it must begin by restoring safety to the spaces where our children learn, play, and believe. We cannot build a thriving nation while traumatizing its youngest citizens. We owe them more than protection. We owe them acknowledgment, empathy, and the promise of a future in which no child must carry the weight of policy on their small shoulders.

That is not only an act of compassion — it is an act of national renewal.

Jack Hill is a diversity consultant, child advocate, journalist, and writer.