Immigrants already have less health care access, and new rules will make it worse | Opinion

Research shows that immigrants pay more in taxes and health premiums than they receive in benefits.

The survivors and families who lost loved ones in the El Paso, Texas, shooting have a difficult road ahead as they deal with grief, trauma, and lasting physical injuries. These challenges are likely to be compounded by another issue for some of the victims: newly strengthened policies that limit public health-care benefits for immigrants.

The suspected shooter in El Paso was allegedly targeting Latino immigrants, and several of those killed or injured were not U.S. citizens. All of the survivors and victims’ families may struggle with access to medical care, but the struggle is likely to be harder for those not born in the United States.

About 23% of immigrants who are in the U.S. legally are uninsured, compared with 8% of citizens, while about 45% of immigrants in the country illegally have no health insurance. In part that is because, while immigrants are more likely than citizens to have full-time jobs, their jobs are less likely to offer health coverage. Even El Paso’s survivors who had employer health coverage before the shooting are at risk of losing it if they are unable to work because of injuries or trauma and have to give up their jobs.

Legal immigrants who lose employer health coverage can apply for Medicaid, known as Medi-Cal in California. However, a 1996 federal law limited Medicaid eligibility to certain categories of “qualified” immigrants in the U.S. legally. In many states, those who qualify must go through a five-year waiting period, and Texas has imposed additional restrictions, putting eligibility out of reach for all but a few.

Even immigrants who are eligible for Medicaid don’t always sign up. As many as 75% of uninsured immigrants without documentation may be eligible for Medicaid, but don’t enroll because of confusion about who is eligible or fear of imperiling their family’s status.

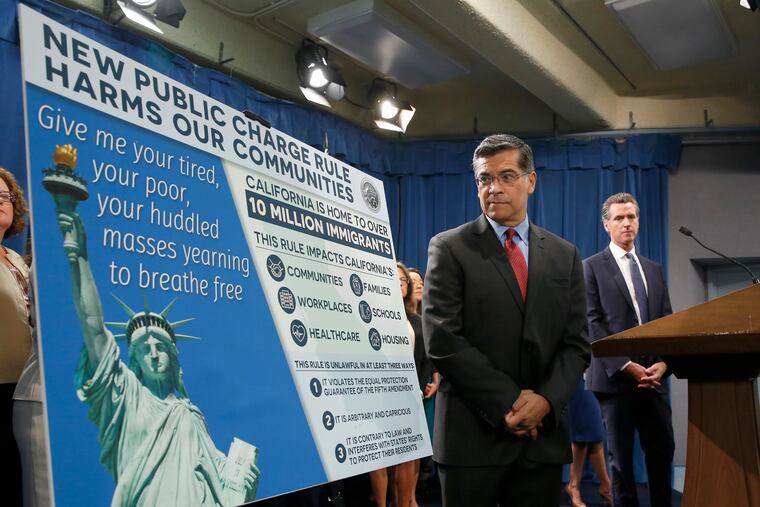

The Trump administration recently added another barrier to Medicaid enrollment. Starting Oct. 15, immigrants who have enrolled in Medicaid are at risk of being disqualified from becoming permanent residents or citizens. In the case of some El Paso survivors, the new rules could potentially require choosing between getting needed medical care now and the chance to become a citizen down the road.

In most states, immigrants without documents, including DACA recipients, are ineligible for Medicaid or subsidies for coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Medicaid may pay for emergency services in some instances, but in the case of the El Paso survivors, who are likely to need ongoing care, that won’t be enough. El Paso’s victims who can’t find health coverage in this unforgiving system will have a stark choice: deferring needed medical care or amassing medical debt.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Extending public benefits to those without documents has a long history in the United States. Public schools, for example, are open to all residents, and federal law prohibits public schools from asking about immigration status.

The U.S. could apply the same approach to public health-care coverage that it applies to public education. And while the current Congress seems unlikely to extend Medicaid to those living in the U.S. illegally, individual states have wide latitude to set eligibility requirements using state funds. California, for example, has provided Medicaid coverage for children lacking legal status since 2016 and recently extended the program to young adults up to 25.

Research shows that immigrants pay more in taxes and health premiums than they receive in benefits, and providing broader access to medical care could help level things out.

The El Paso families in particular shouldn’t have to struggle to get medical care or be burdened by unaffordable bills. We can make a lasting commitment to them, acknowledge the value of immigrants, and elevate the moral standards of our health-care systems by making existing public health benefits available to all those who meet their criteria, regardless of legal status.

Alex Gertner is a medical student and doctoral candidate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Paul Shafer is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Law, Policy and Management at Boston University. A version of this piece first appeared in the Los Angeles Times.