Under Trump’s assault, Black educators must preserve history

Trump’s targeting of the President’s House is a racist attempt to change American history to reflect a lie. It means federal institutions cannot be trusted to preserve history accurately.

In March, the Trump administration issued an executive order that prohibited the “expenditure on exhibits or programs that degrade shared American values, divide Americans based on race.” The order targeted numerous museums of the Smithsonian Institution, as well as Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia.

The result of this targeting is the planned or executed removal of artifacts. In other words, the erasure of history.

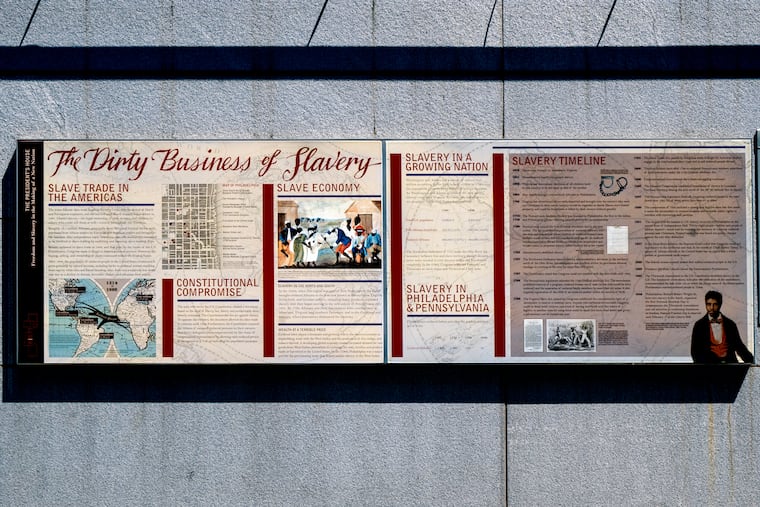

The President’s House that housed George Washington and John Adams, as part of Independence National Historical Park, has come under fire from the Trump administration for “inappropriately [disparaging] Americans past or living.”

The President’s House includes information about the Africans enslaved by Washington — including Ona Judge, who escaped her captivity with the support of free Black Philadelphians, never to return to enslavement. The exhibits that feature the information have been part of the site since 2010, and are the result of a sustained campaign by local lawyer Michael Coard and a community group known as the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition.

To be clear, Donald Trump’s targeting of the President’s House is a racist attempt to change American history to reflect a lie about the African American experience in this country.

» READ MORE: Teaching Black history shouldn’t fall solely on the shoulders of Black people | Opinion

It means federal institutions cannot be trusted to preserve history accurately — namely, the nation’s fraught relationship with Black Americans and other people of African descent. Sadly, textbooks could rarely, if ever, be trusted to preserve that history accurately, making these exhibits even more important as a teaching tool for young people and adults alike.

What’s the response we need in the moment?

Educators must begin preserving history, if they haven’t already begun doing so — especially Black educators.

Social studies teachers may be the educators who first come to mind for this work; however, no educator should limit themselves because of their content area or racial/ethnic background. History matters and is part of any content area, from the arts to science, literature, and even mathematics.

Likewise, all people should be — must be — invested in history because history tells the story of who we are. History shows us from whence we came, where we went wrong, and how we can reach the places we want to go.

That’s true for people of color and white people.

» READ MORE: For GOP voters feeling the pain of Trump’s cuts, a realization dawns: We’ve had our pockets picked | Opinion

But for African Americans, history is more than just knowledge. History — our history here, throughout the Americas, and in Africa — is a systematic study wrapped around our collective DNA. With so many of our individual family stories lost to the original sin that was chattel slavery, Black history is an essential educational component that is vital to informing our community’s identity.

When I teach history, I approach it as a sacred rite in which the ancestors are able to reach back across the eons to tell their own stories as Black people in a society that continues to deny the truth of who they were, how they came to these shores, and how they labored to make America what it is.

In response, I keep history in my home library — books, academic journal articles, newspaper and magazine articles, and videos. I use these to teach my students, my children, and the readers of my writing. I fight against the erasure of Black history in this way.

Black educators must find their own way to carry on this fight, and it begins with preserving history. Teaching, displaying, or writing Black history means nothing if white nationalists in government have been allowed to erase it from our memory. Teaching, displaying, or writing Black history will only matter if we preserve it so that we can share it with the world.

As we embark on the dawn of another school year, my challenge to educators — specifically Black educators — is to research, learn, and preserve Black history.

Find and save academic journal articles written by scholars of color.

Purchase photo books that capture history, like those by Gordon Parks and Bruce Talamon.

Build your personal library of books. Visit historical markers in your area and document them. Visit your local historical societies. Join these and other organizations and document what you learn.

Research, learn, and preserve. We, the teachers, must once again become the students, to become better teachers and to become archivists in a post-truth and anti-Black society, because the war against Black history won’t be won in the legislature or the White House. Instead, it will be won in your libraries, your living rooms, and your classrooms.

It will be won by the keepers of the oral tradition who end up preserving the histories that we share with them in the libraries of their minds.

Rann Miller is an educator and freelance writer based in South Jersey. His Urban Education Mixtape blog supports urban educators and parents of children attending urban schools. Miller is also the author of “Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids,” which was reissued in 2024. @RealRannMiller