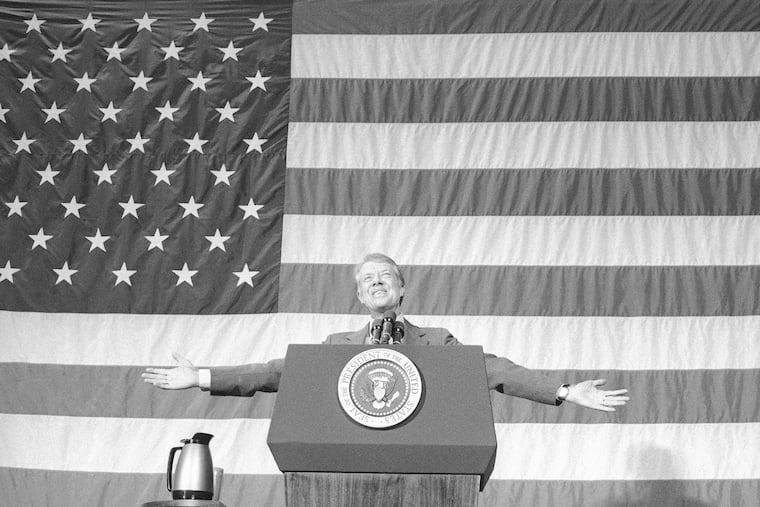

Jimmy Carter, a humble centenarian

On the former president's 100th birthday, Chris Matthews — once a Carter speechwriter — reflects on his old boss' journey from Plains, Ga., to Pennsylvania Avenue.

On Tuesday, Jimmy Carter turned 100. For those who celebrate smaller birthdays, it might be good to consider how this man from faraway Plains, Ga., made it all the way to the White House.

I can tell you part of the answer. In the spring of 1974, a letter arrived at my family’s address in Northeast Philadelphia. It showed up just after my defeat in a primary race for U.S. Congress.

The letter encouraged me to “stay actively involved in Democratic politics.” I should not give up. “I would appreciate any information or advice you might have that would help our efforts in Pennsylvania or other states. Please feel free to contact me personally or Hamilton Jordan.” It was signed “Jimmy Carter.”

How did the candidate, soon to be laughed at as “Jimmy Who?” recruit people to his 1976 campaign?

This way.

How about sleeping on a volunteer’s sofa? Instead of staying in high-priced hotels and traveling with an entourage, Carter asked volunteers to put him up for the night. A speechwriter for President John F. Kennedy said it best: “How can you vote against someone who slept on your couch?”

He did so with a powerful message of humility.

Carter also said he wouldn’t “lie” to the American people. But at the time, this simple claim had an impact. Years later, he told me that after the tumultuous decade that preceded his presidential run, the nation was in need of healing.

“The country was in a quandary,” he said. “We had lost Bobby Kennedy. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. We had been through Watergate. All those things had happened just before I ran. I was a fresh face: a peanut farmer from a little town like Plains, Ga. And, you know, they were looking for something different.”

Carter was authentic, and he was new. People saw those TV ads of him working in the fields. They saw a peanut farmer from rural Georgia out there asking for their votes. And that’s why he won caucuses and primaries from Iowa to New Hampshire to Florida and Pennsylvania.

My friend Jerry Rafshoon, the man who made those ads, told me he didn’t have to fake any of it. His candidate was already out working in the field. He was a peanut farmer. “Let’s get going,” he recalls Carter barking while he shot a commercial. “I’ve got a delivery to make.”

Rafshoon, now a pal of mine, is 90 himself. He once told me about the night Carter bragged about his advantages politically: “Not a lawyer, Southerner, farmer, 300 days a year to campaign” — he was a lame-duck governor — “ethics, not part of the Washington scene, religious.” For better or worse, they were the qualities of Jimmy Carter.

In January 1977, Carter began his presidency by thanking his predecessor Gerald Ford “for all he has done to heal our land.”

“It was a clean election,” Carter reminded me. “We never said a negative word about each other. I never did bring up the fact that he had pardoned [Richard] Nixon, which could’ve helped.”

Carter then broke precedent by walking down Pennsylvania Avenue in the inaugural parade. It’s an idea he’d picked up, he said, from Wisconsin Sen. William Proxmire, a physical fitness buff.

“I was a fresh face: a peanut farmer from a little town like Plains, Ga.”

“I told the Secret Service what I was gonna do. But I just informed them. I didn’t ask for their permission.”

It was simply a way he wanted to “break the ice” for a new presidency.

The first thing Carter did when he got into office was to pardon the people who wouldn’t fight in Vietnam but had gone to Canada. “I just thought it was time to get that bad episode in America’s history out of the way and not to have to fight it about it anymore.” He wanted to end the American debate over Vietnam.

He did the same with Israel and Egypt. At Camp David in 1978, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin forged a treaty that has met the test of time. Even amid the horror and death of Israel’s fight with Hamas in Gaza, Egypt has kept its peace with the Jewish state.

Winning Senate backing for the Panama Canal Treaty, Carter once told me, was even harder than getting elected president. That, too, has lasted and kept us from another war in Central America.

But in 1979, Carter faced the challenge that would end his chances for a second term. It was the taking of American diplomats by Iranian students. I was in the White House as a presidential speechwriter the Sunday evening right before the 1980 election. That’s when Carter told the country that the 50 U.S. hostages would not be freed under his watch. ”I wish I could predict when the hostages will return,” he said. “I cannot.”

Carter believed, rightly or wrongly, that he could not go to war with Iran over that country’s blatant violation of diplomatic rights. Other presidents, obviously, would have. It might have given Carter a second term.

“We worship the prince of peace, not war,” Carter told me once. “I think it’s a basic human right, living in peace.”

The voters thought him wrong. Someday, we’ll see how history views him.

Chris Matthews anchored MSNBC’s “Hardball” for a quarter century. Before joining the network, he served as a speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter.