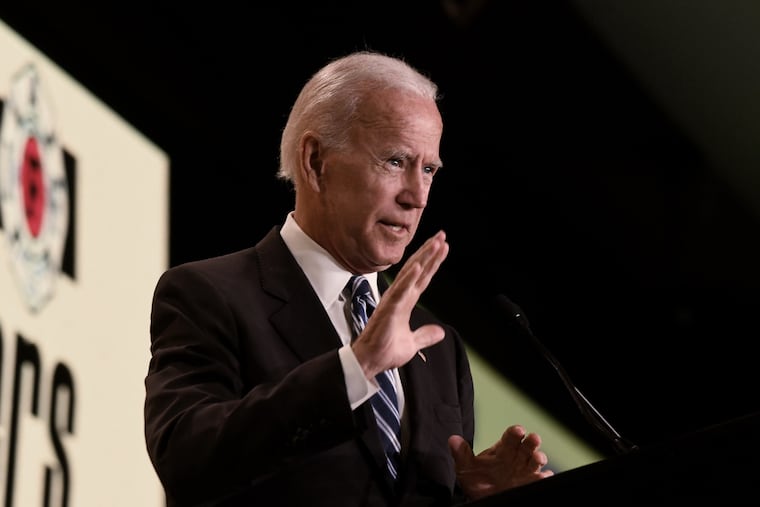

Joe Biden’s not alone in spreading myths about busing and segregation | Opinion

Joe Biden's rediscovered comments on busing dredged up some ugly myths, which we should discard once and for all.

Hey, did you hear the news? Joe Biden opposed busing!

That’s not news to historians, who have known about it for a long time. But an obscure 1975 interview with Biden — unearthed by the Washington Post last week — has revived debate over the politician’s record on race, including his long-standing fight against busing children to integrate schools. It’s also dredged up some ugly myths, which we would do well to discard once and for all:

Myth One: Busing harmed white people.

Myth Two: Black people opposed it.

Myth Three: It didn’t work.

In 1975, Joe Biden was a first-term senator. He had won election three years earlier on a campaign favoring busing. But he quickly changed his tune, as more and more white constituents told him they didn’t want it.

“I do not buy the concept, popular in the ‘60s, which said, ‘We have suppressed the black man for 300 years and the white man is now far ahead,” Biden told a Newark, Del. newspaper, in the antibusing interview the Post quoted. “In order to even the score, we must now give the black man a head start, or even hold the white man back. I don’t buy that.”

Translated: If white students are mixed with black ones, they’ll suffer. But there was little evidence for that, then or since. Most recently, a 2015 federal study confirmed that white students scored roughly the same on standardized math tests regardless of the density of black peers in their schools.

Nor did black Americans reject busing as racist, as Biden suggested. “What it says is, ‘In order for your child with curly black hair, brown eyes, and dark skin to be able to learn anything, he needs to sit next to my blond-haired, blue-eyed son,’” Biden said. “Who the hell do we think we are, that the only way a black man or woman can learn is if they rub shoulders with my white child?”

Biden’s comment prefigured Clarence Thomas’ 1995 Supreme Court opinion, which said court-ordered integration was “based upon a theory of black inferiority.” And surely African Americans have been divided on busing, which often required black students to move to white schools instead of vice versa.

But in a Harris poll from 1981, during busing’s heyday, 87 percent of parents whose children were bused to promote integration viewed the experience as either “very satisfactory” (54 percent) or “partly satisfactory” (33 percent); only 11 percent deemed it “unsatisfactory.” Black parents, especially, believed integrated schools would provide their kids with a better education.

And they were right. African Americans attending integrated schools have experienced higher rates of employment — and larger salaries — than peers of similar backgrounds who went to segregated schools. They’re also less likely to have children as teenagers, or to be incarcerated as adults.

But our public schools are now more segregated than they were in the 1970s. So busing failed, right? Wrong. Busing sharply increased integration until the 1990s, when Thomas and other conservative judges began to loosen the pressure on school districts to desegregate. And, not surprisingly, schools resegregated after that.

Joe Biden’s hometown of Wilmington is a case in point. In 1978, a federal court ordered the city school district to combine with 10 suburban ones so that kids could be bused between them. By the end of the 1980s, Delaware was one of the two states with the most desegregated schools in the nation.

But in the 1990s, as the Supreme Court turned away from school integration, Wilmington did the same. In 1995, a judge declared that the schools were integrated and hence freed from the prior federal order. Five years later, the state passed a measure requiring students to attend the school closest to their homes. By 2010, 64 percent of black students were enrolled in predominantly minority schools, a tenfold increase from 1989.

So busing didn’t fail; instead, we failed to keep it going. But in his 2007 autobiography, an unrepentant Joe Biden insisted that busing was a “liberal train wreck.” Likewise, New York mayor Bill de Blasio recently warned against busing children outside their neighborhoods. In Boston, where de Blasio grew up, busing “absolutely poisoned the well,” he said. “I think history is on my side here.”

Actually, it isn’t. In most places, busing didn’t trigger the violence and controversy that Boston experienced. The train wreck happened afterward, when the nation turned away from the simple ideal that children of different races should attend the same schools. The real question is whether we can revive that dream. And, most of all, whether we have the will to do so.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author, with Emily Robertson, of “The Case for Contention: Teaching Controversial Issues in American Schools” (University of Chicago Press).