How passive voice makes the Roger Stone indictment sound less damning than Johnny Doc’s | The Angry Grammarian

Is Robert Mueller saving his active voice for when there will be zero ambiguity about whom he’s implicating?

Remember what you were taught about the passive voice?

It’s bad. Don’t use it. If you have to use it, you should feel really sorry about it, hang your head low, and say a few Hail Marys first.

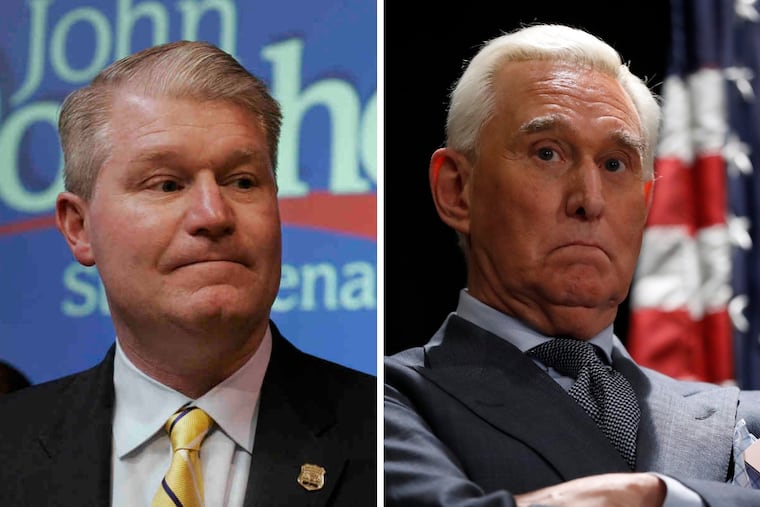

A close read of the Johnny Doc and Roger Stone indictments reveals that the U.S. District Courts of Eastern Pennsylvania and D.C., respectively, are wielding that passive voice judiciously.

The 116 counts against Local 98 leader John Dougherty and friends are a tour de force of active, past-tense verbs, meant to directly implicate those named in the indictment: They say Johnny Doc “controlled,” “used,” “conspired,” “stole,” “misrepresented,” “directed” — all in the opening paragraphs. The court wants no ambiguity regarding who, exactly, performed these actions. The language is dramatic and damning.

The Roger Stone indictment provides a fascinating contrast. Like the charges against Johnny Doc, it’s written mostly in active voice, but at a key moment on page 4, special counsel Robert Mueller switches to the passive voice: “After the July 22, 2016 release of stolen DNC emails by Organization 1, a senior Trump campaign official was directed [emphasis added] to contact Stone about any additional releases.”

This is weird. And not an accident.

Legal scholars will offer myriad explanations for why Mueller wouldn’t want to name who directed the senior Trump campaign official. It would have to be someone really senior, perhaps the candidate himself, and maybe the special counsel doesn’t want to tip his hand about what, if anything, he’s serving at the end of the investigation. But this is one case where the ambiguity that the passive voice offers is likely a weapon, not a weakness.

As a general rule, writing in active voice is preferable. It’s more precise — about who is performing an action — and concise, in that it usually saves you a couple of words. Take the first sentence of this article: If you want to give your teachers credit (which, come on, you should), it would read: “Remember what you were taught by your English teachers about the passive voice?” — a sentence obviously inferior to “Remember what your English teachers taught you about the passive voice?”

Presumably, if you’re going to all the trouble of typing up a massive indictment, you’ll want to watch your language. So we have three grammatically suspenseful options:

A) Members of the U.S. District Court of Eastern Pennsylvania much better remember what their English teachers taught them, and showed it in the papers filed last week. Score one for Pennsylvania schools.

B) Robert Mueller knows his grammar, but he doesn’t know which very senior Trump campaign official gave orders to another already senior campaign official. Mueller is using passive voice to say everything he knows, nothing more.

C) Mueller is saving his active voice for when there will be zero ambiguity about whom he’s implicating.

At that point, there won’t be enough Hail Marys in the world.

The Angry Grammarian looks at how language, grammar, and punctuation shape our world, and appears biweekly. That’s every other week, not twice a week, friends. Send comments, questions, and be-verbs to jeff@theangrygrammarian.com.