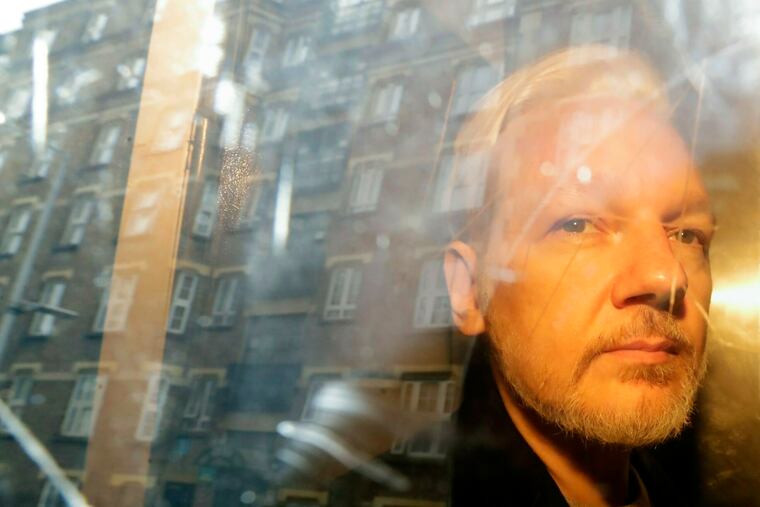

Julian Assange is not a journalist. The Justice Department is right to indict him | Marc Thiessen

The WikiLeaks founder does not get to aid and abet our enemies, put countless lives at risk, and then hide behind the First Amendment.

WASHINGTON — Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has called WikiLeaks a “nonstate hostile intelligence service.” Apparently Julian Assange agrees. In its new 18-count indictment of Assange for multiple violations of the Espionage Act, the Justice Department notes that Assange told former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning that WikiLeaks had originally described itself as an “intelligence agency” for the people.

Now, at long last, the head of that enemy intelligence agency is facing a possible 175 years in a federal penitentiary for his theft of American secrets.

The damage Assange has done is unfathomable. In 2010, he exploded what he called his “thermonuclear device” — releasing a tranche of more than a quarter of a million classified State Department diplomatic cables, all unredacted. According to the indictment, those cables “included names of persons throughout the world who provided information to the U.S. government in circumstances in which they could reasonably expect that their identities would be kept confidential. These sources included journalists, religious leaders, human rights advocates, and political dissidents who were living in repressive regimes and reported to the United States the abuses of their own government, and the political conditions within their countries, at great risk to their own safety.”

The indictment cites specific examples of sources WikiLeaks burned inside China, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Moreover, Assange’s decision to release 90,000 Afghanistan war-related activity reports also revealed the identities of at least 100 Afghans who were informing on the Taliban. The indictment quotes a New York Times interview with a Taliban leader who told the paper, “We are studying the report. We knew about the spies and people who collaborate with U.S. forces. We will investigate through our own secret service whether the people mentioned are really spies working for the U.S. If they are U.S. spies, then we know how to punish them.”

Assange’s stolen classified documents didn’t just find their way to the Taliban; the indictment points out that WikiLeaks copies were also found in Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. During the raid that killed the al-Qaida leader, U.S. forces recovered “a letter from bin Laden to another member of the terrorist organization al-Qaida in which bin Laden requested that the member gather the DoD material posted to WikiLeaks” as well as a response from that al-Qaida operative providing him with the secret U.S. government documents Assange had provided.

Indeed, Assange’s disclosures nearly blew the bin Laden operation. Just one week before the raid, Assange released his "Gitmo files "which contained information that could have tipped off bin Laden that the CIA was closing in on him. One of Assange’s stolen documents — the file on Abu Faraj al-Libi, al-Qaida’s captured operational commander — revealed that Faraj had “reported on al-Qaida’s methods for choosing and employing couriers, as well as preferred communications means”; that he had “received a letter from UBL’s designated courier” who was “the official messenger between UBL and others in Pakistan”; and that “in mid-2003, [Faraj] moved his family to Abbottabad, and worked between Abbottabad and Peshawar,” Pakistan. The CIA tracked bin Laden down to Abbottabad by following his courier, thanks, in large part, to information provided by Faraj. Had bin Laden read that document detailing what Faraj had told the agency, he could have known that the United States had made the connection between his courier and his Abbottabad hideout. Fortunately, U.S. Special Operations forces did not give bin Laden time to figure it out.

The indictment leaves out much of the damage Assange did, such as his 2014 release of classified CIA documents exposing how CIA operatives maintain cover while traveling through airports; his 2016 release of documents detailing European Union military operations to intercept refugee boats traveling to Europe from terrorist-infested regions along the Libyan coast; and his 2016 exposure of top-secret documents describing NSA intercepts of foreign government communications.

Some are concerned that the newest Assange indictment will help set a precedent to go after investigative journalists who publish classified information. But as I wrote in 2010, unlike “reputable news organizations, Assange did not give the U.S. government an opportunity to review the classified information WikiLeaks was planning to release so they could raise national security objections.” So responsible journalists have nothing to fear.

Regardless, Assange is not a journalist. He is a spy. The fact that he gave stolen U.S. intelligence to al-Qaida, the Taliban, China, Iran and other adversaries via a website rather than dead-drops is irrelevant. He engaged in espionage against the United States. And he has no remorse for the harm he has caused. He once called the innocent people hurt by his disclosures “collateral damage” and admitted WikiLeaks might get “blood on our hands.” Sorry, he does not get to aid and abet our enemies, put countless lives at risk, and then hide behind the First Amendment. The Justice Department is right to indict him for his crimes.

Marc Thiessen writes a twice-weekly column for The Washington Post on foreign and domestic policy. He is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and the former chief speechwriter for President George W. Bush. @marcthiessen