The way we treat older adults transitioning to long-term care is ‘garbage’

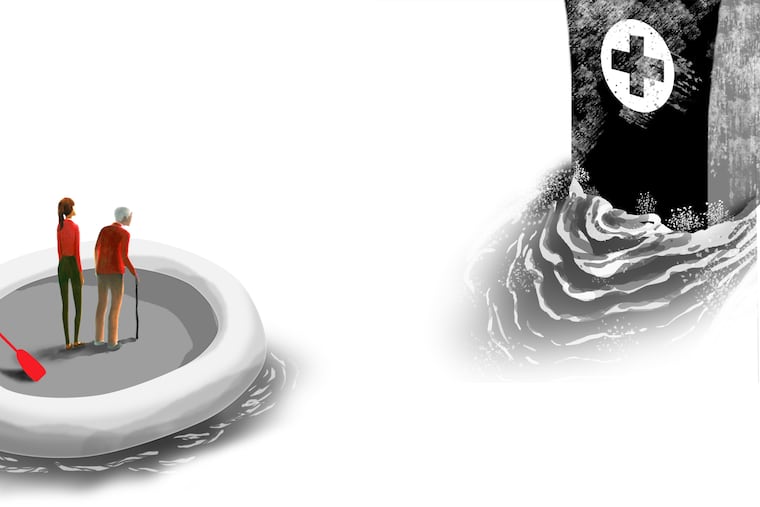

There is no coordinated system in place to help older adults and their families transition to long-term care and navigate the inevitable healthcare challenges they will face.

I am not new to end-of-life care — as a nurse and someone who has worked in healthcare for most of my life, I have helped numerous friends, family, patients, and clients at the end of their lives.

Yet, the transition to long-term care for older adults is vastly different. Over the past few weeks, I have witnessed the demoralizing treatment of this firsthand as family members close to me have tried to manage their loved one’s urgent hospitalization and the fallout afterward; it was a wake-up call.

My 80-year-old relative was diagnosed with metastatic cancer seven years ago. During the pandemic, they had emergency surgery as their cancer spread to their spine and caused partial paralysis in their legs. The surgery was successful, and for a long time, medication kept the cancer contained. But last month, the paralysis began again, and they were back in the hospital requiring another urgent spinal surgery.

At first, their acute care was phenomenal. Then, as they became physiologically stable, and it became clear they couldn’t go home but would need long-term care, everything changed.

I watched as my family members, over the course of two weeks, grew increasingly overwhelmed, exasperated, and exhausted. They began to look as though they themselves were going to require hospitalization. The amount of information being thrown at them, in no coordinated way, was utterly overwhelming. In contrast, the lack of information being shared with them was similarly overwhelming and stupefying.

Though my family members were at their loved one’s bedside more than eight hours a day while in the hospital, and repeatedly asked the medical team to discuss any plans with them, their loved one’s healthcare proxy, the team continued to only relay pertinent information to the patient who was in excruciating pain, on pain meds, is hard-of-hearing, and was recovering from spine surgery and anesthesia .

Not surprisingly, the information rarely made it back to my family members. Not once during the week postsurgery, as they were trying to plan for the looming hospital discharge and the associated next steps, did that happen.

At no time did anyone from the surgical or oncology team discuss follow-up plans with my family members. This sparked a cascade of misinformation and omissions that became the foundation for the steep learning curve that is rehabilitation and long-term care in our healthcare industry.

Due to the progression of the cancer on the spine and the ensuing paralysis, my family’s loved one needed to go to acute rehab from the hospital, but what acute rehabs were available, where they were located, how long one can stay and then where they go afterward, how it would be decided, and how it would be paid for was a mystery for my family to decipher.

Their loved one would need to start radiation therapy once the surgical wound healed, but how they would be transported from the acute rehab to the medical center and when that would begin was also, apparently, for the family to figure out. At one point, my family member asked the social worker how transportation to the radiation appointment would work; the social worker shrugged their shoulders and told them to try an Uber.

An Uber, for a medically fragile, at the time stretcher-bound, individual. It would be funny if it were not contemptible.

As my family member’s loved one became more stable and progressed in their rehabilitation, their follow-up medical care became the next problem to be solved.

My family member asked the social worker how transportation to the radiation appointment would work; the social worker shrugged their shoulders and told them to try an Uber.

Oncology appointments were scheduled while at acute rehab; luckily, they could be done virtually. To our surprise, though, the acute rehab personnel would take no responsibility in assisting their patient in attending these medically necessary appointments. They refused to help turn on the iPad or log in to the medical portal for the appointment. Once again, it was the family’s responsibility to figure out how this would happen.

Ultimately, my family member had to physically go to the acute rehab to turn on the device and log their loved one into the portal. Dealing with an ill and injured loved one is hard enough while juggling your own life responsibilities, but requiring family members to drive 40 minutes (each way) in the middle of a weekday to an acute rehab facility with licensed medical providers — to assist the facility’s own patient with their necessary medical appointments because the facility’s licensed medical providers refuse — is yet another unnecessary and callous hurdle to make families jump.

In situations such as I have described, families have no control over some things, yet are expected to control the minutest details of others. Make it make sense.

I am not naive to the plethora of troubles that come with being sick, injured, low-income/low-resources, or elderly in this country.

I ran a nonprofit organization years ago that helped people pay for medical expenses. I worked with clients who were not only trying to keep their loved ones alive but were also trying to manage and pay for their care. I repeatedly witnessed how our healthcare industry put up every possible roadblock and hurdle; how loved ones became increasingly despondent.

In the U.S., there are over 61 million older adults, those aged 65 or older — this is 18% of the population. This number is expected to grow to 22% of the population by 2040. That will be close to one-quarter of the U.S. population. Yet, there is no coordinated system in place to help older adults and their families transition to long-term care and navigate the inevitable healthcare challenges they will face — let alone face them with grace and dignity.

I repeatedly witnessed how our healthcare industry put up every possible roadblock and hurdle; how loved ones became increasingly despondent.

The “not my problem” “hot potato” approach our healthcare industry has taken is criminal.

With nowhere else to turn to help my loved ones, I reached out to a colleague who specializes in palliative care. They provided helpful resources and echoed what seems to be the sentiment of many providers: “Our ‘system,’ it’s garbage.”

Many patients and families who have gone through this experience know this to be true. Yet, we continue to perpetuate, accept, or be resigned to a system that treats older adults and their families, as my colleague accurately stated, like garbage.

Which is mind-boggling, as most of us, if we are lucky (or unlucky, given the circumstances), will grow old. Most of us have relatives who will grow old. Almost all of us who grow old will need some long-term care — and yet, based on our experience and the experiences of so many others, there is no system in place.

None of the resources we eventually found came from any healthcare provider or social worker in either the hospital or the acute rehab.

None.

Only after using ChatGPT and reaching out to colleagues were we able to start putting the pieces together. ChatGPT recommended our local county aging corporation, which provided helpful resources for transportation and the Pennsylvania Elder Law hotline.

Through this whole process, we have remarked — and felt genuinely nauseated over — what other older adults who need long-term care do if they don’t have family support or financial resources. We are still at a loss.

But I am not about to shrug my shoulders or be resigned. I am not willing to place the burden back on the sick and aging, nor their families. I implore my healthcare colleagues to acknowledge the faults in the system, accept the burden of care, and do better.

Marion Leary is a nurse, public health advocate, and activist.