Strangers sprang into action to save a life on the subway. What if policymakers shared these values? | Perspective

When a train rider overdosed, people came together to save his life. What if our national policy reflected the values in that subway car?

As an emergency medicine physician for more than 20 years, Jeanmarie Perrone, professor of Emergency Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, has been involved in thousands of rescusitations. This one, on a Philadelphia subway a few weeks ago, was different.

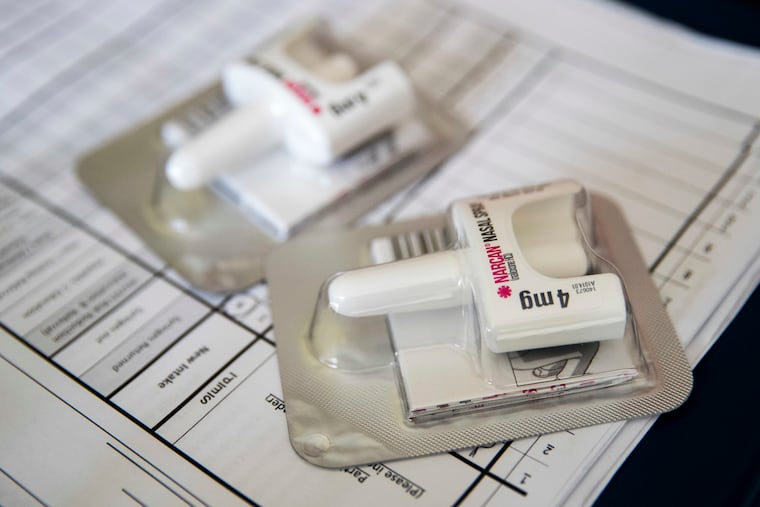

The train wasn’t crowded on an early evening in May as Perrone got on in Old City. Suddenly, a young man burst into the subway car and yelled, “Narcan! Does anyone have Narcan?” Perrone, who always carries Narcan with her, said she did and the young man led her quickly through the train to where another young man was lying face up, purple-blue, clearly not breathing. A bystander was conducting CPR, while another had called 911, and a third had dispatched someone in search of Narcan.

Perrone fumbled in her purse and found the still-sealed box with two doses of Narcan. Although she had demonstrated the use of Narcan countless times, this was the first time she had to rip open the box, and undo the packaging in an emergency. Her fingers found the nasal spray and she squirted it into the man’s nostril, while the CPR continued. She waited a few minutes to see if the first dose reversed the overdose.

In those anxious moments, she thought about the community that had sprung up instantly around this young man, all dedicated to preventing his death. They were a diverse group, all with life stories of their own, tied together now in common purpose. To a stranger they were saying, We see you, and you’re important.

But no breath emerged. Perrone reached for the second dose of Narcan and sprayed it into the man’s other nostril. He was still purple-gray. She waited a few more moments, as the bystander continued CPR. And still no breath emerged. Sometimes they don’t come back, she thought sadly.

Perrone rubbed the bridge of the man’s nose, trying to spur some response to the Narcan. The man took in a tiny, shallow breath, and then stopped. Perrone kept rubbing his nose. He took another tiny breath, and stopped again. Perrone wished she had carried a pocket mask with her to start rescue breathing. But in about three minutes, he had regained a pulse, and his breathing steadied.

Perrone relaxed a bit, and looked around. EMS came about 10 minutes later, and took the man to the emergency department. It would have been too late without the collective action of the subway riders. “You are the heroes,” she said, tears streaming, “You just saved his life.”

This story is reenacted many times a day, in homes and streets, in businesses and libraries and restaurants. It shows that ordinary bystanders can identify an overdose and know what to do. It wasn’t Perrone’s presence as an emergency medicine physician that saved the young man; it was a group of strangers, one of whom carried Narcan, all united in the belief that this man was somebody, and that his life mattered.

The ending to this particular story has yet to be written. A Narcan rescue can be a bridge to treatment and recovery. The young man was taken to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, which has a program linking people with opioid use disorder to immediate treatment and ongoing follow up. A patient brought into the emergency department after an overdose could meet with a certified recovery specialist, and leave with a plan, the first doses of a stabilizing medication (buprenorphine) and a peer counselor for further information and support. While the path to recovery may not be an easy or direct one, the health system is also forming a community around these patients to given them the best chance at survival.

Amidst an opioid epidemic that claimed more than 47,000 lives last year, there is a lesson in this for policymakers. What if our national policy reflected the values in that subway car? What if we designed and paid for programs to link each person to effective medication treatment, without judgment or stigma? This is both our greatest challenge and a moral imperative. Just ask people on the subway.

Janet Weiner, Ph.D., MPH is co-director of Health Policy for the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.