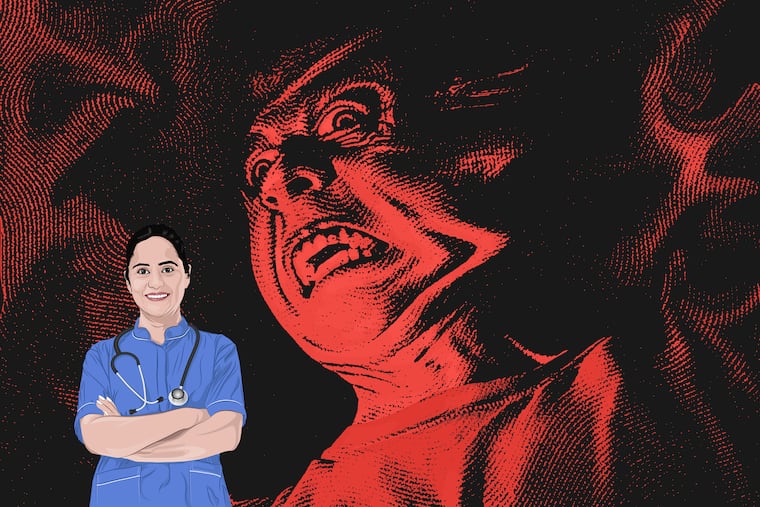

Nurses ‘deserve to feel safe at work like anyone else’

I’ve had water thrown at me, tables tossed while I’ve been in the room; a gentleman raised his cane claiming he would strike me if I didn’t leave his room.

When you think of dangerous jobs where workers can get injured, most people probably imagine construction, firefighting, or police work. You should add nursing to that list.

Of course, it was dangerous to be a nurse during COVID-19, when thousands of health-care workers fell sick — and died. But the profession poses threats besides infectious disease.

The threats are from our own patients, who have become more violent toward us in recent years. During the pandemic, 44% of nurses said they experienced physical violence, while 68% reported verbal abuse.

It’s not just hard to be a nurse during a pandemic. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2018, 73% of all nonfatal on-the-job injuries and illnesses were sustained by health-care workers. Health-care workers were also five times as likely to be physically assaulted while working than all other types of workers. And the rate of workplace violence experienced by nurses has only been increasing.

I’ve had water thrown at me, tables tossed while I’ve been in the room; a gentleman raised his cane claiming he would strike me if I didn’t leave his room. Once, a patient told me he’d call his people to jump me after work. (Thankfully, that didn’t happen. But I was concerned.) Still, I’ve been lucky. I know many nurses who have had much worse experiences.

Once, a patient told me he’d call his people to jump me after work.

Emergency department nurses are especially at risk. One 2009 study of thousands of nurses working in U.S. emergency rooms found that one-quarter said they had experienced physical violence more than 20 times in the last three years. During the same period, one-fifth said they had been verbally abused at least 200 times. Many said they hesitated to report incidents of workplace violence, however, out of “fear of retaliation and lack of support from hospital administration.”

What other profession is required to accept being assaulted with the perpetrators facing no consequences? If a person so much as verbally abuses a bank teller, security will at the very least escort that person from the bank. Someone physically assaults an employee at Home Depot? The police will be called and the assailant may be charged. Attack an RN? Not only will that person not be charged, they can be discharged and return to that hospital. And the nurse who was assaulted may have to accept the attacker being on their floor.

» READ MORE: Violence against health-care workers was rising. Then the pandemic hit, and made things worse.

Many facilities throughout the country have provided de-escalation training for nurses and other health-care workers, in which they learn how to defuse the situation. While these techniques can be helpful, why does it fall onto nurses to protect themselves from aggressive, dangerous patients and family members? At my hospital, and many others, nurses wear panic buttons. What does this suggest about the frequency of assaults committed against nurses? Why are we responsible for our own safety?

Prosecuting assailants — that is what violent patients and family members are — is the only way to effectively increase the workplace safety for nurses and other health-care staff. A process should be in place for immediate filing of charges against perpetrators of violence, if the RN chooses to do so.

In 2020, Pennsylvania made violence against nurses a felony with the passage of Act 51. While this is welcomed news, it won’t have any impact unless aggressive patients and family members are charged. (There should be exceptions, of course; patients with dementia or a traumatic brain injury can become violent but should not be held responsible for their actions.)

There is progress being made in the health-care industry. For example, the University of California, Davis Medical Center recently implemented a program called the Behavioral Escalation Support Team, known as BEST. This team is composed of staff trained in mental health care and de-escalation tactics and can step in when a staff member calls them to intervene. But the purpose of the team is merely to calm the aggressive patient. The patient faces no consequences.

Whenever the topic of prosecuting violent patients or family members arises, I typically hear two rebuttals: Patients and family members in hospitals are experiencing great stress and therefore deserve some leeway, and prosecuting patients and families could damage a hospital’s reputation and cause it to lose patients and, therefore, revenue.

I reject both of those arguments.

Those who engage in violence against others are criminals. Period. That violence against nurses is somehow unique is ridiculous.

We deserve to feel safe at work like anyone else. And we don’t.

Timothy Cragg is a nurse in West Philadelphia.