What would Benjamin Franklin think of today’s criminal justice? | Opinion

When I was invited to speak about criminal justice reform in honor of Franklin’s birthday later this month, I tried to imagine what he would make of his hometown today, how Philadelphia’s current dispensation of justice would look through Franklin’s bifocals.

In addition to being a statesman, inventor, publisher, and sage, Benjamin Franklin was an ardent prison reformer. Scandalized by the cruelty of contemporary penal practice, he became an early member of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons.

When I was invited to speak about criminal justice reform in honor of Franklin’s birthday later this month, I tried to imagine what he would make of his hometown today, how Philadelphia’s current dispensation of justice would look through Franklin’s bifocals.

First, I think he would applaud John Wetzel, the state corrections secretary, for trying — albeit with limited success so far — to learn from prisons in Germany and Scandinavia. In much of western Europe, the emphasis is on equipping inmates for something other than a life of crime when they return to society. Sentences are shorter, cellblocks often resemble college dorms, and opportunities for self-improvement are plentiful. This is not regarded as pampering but as a public interest.

“Every inmate will come out and be our neighbor," a Norwegian warden told the Inquirer during a Wetzel-hosted visit to Philly in 2017. “So, what kind of neighbors do we want?”

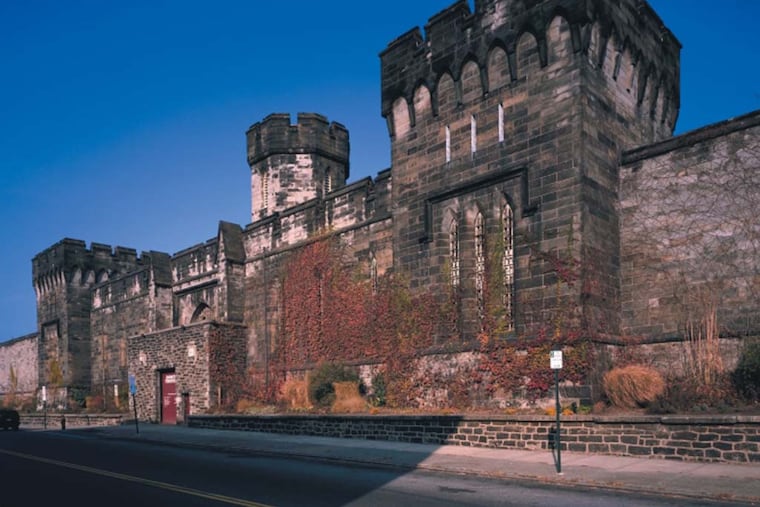

That is what Franklin and the Prison Society had in mind when they conceived America’s first modern penitentiary, a Quaker-inspired alternative to the squalid county jail, the public hangings, and the supposedly corrective shame of public lashing and the stocks. The answer to crime, the society declared, was “restoring our fellow creatures to virtue and happiness.” At the Eastern State Penitentiary, the regimen stressed the reformative value of isolation, contemplation, and mastering such crafts as shoemaking and weaving.

The isolation part, we now know, was seriously misguided. As a PBS investigation concluded in 2017, solitary is often overused and can do more harm than good — and more than 30 states are trying to reform it. A scientist at heart, Franklin today would have read the compelling research on the effects of solitary confinement and been appalled that Pennsylvania still lags other jurisdictions in taking that knowledge to heart.

Still, on Wetzel’s watch, which began in 2010, the state’s prison population has been reduced, one prison has been closed, and violent crime and recidivism have continued to decline, according to the Council of State Governments Justice Center.

I suspect Franklin would have recognized a kindred spirit in Larry Krasner, the reformer Philadelphia’s voters chose a year ago as their district attorney. As a founding father, Franklin would probably approve of the way Krasner wields the Eighth Amendment protections against “excessive bail” and “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Krasner has stopped penalizing the poor with bail for minor crimes and ordered his prosecutors to seek sentences that suit the crime rather than scoring points in a tough-on-crime contest.

It’s a reasonable bet Franklin would share Krasner’s distaste for mandatory minimum sentences, which can result in outlandish prison terms and have been used by prosecutors in some venues to browbeat confessions out of innocent suspects. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 15 percent of felony convictions overturned in the past 30 years were the result of innocent people pleading guilty.

Franklin famously declared that “it is better a hundred guilty persons should escape than one innocent person should suffer,” a maxim, he added, “that has been long and generally approved.” Though not, apparently, approved by some lawmakers in Harrisburg or by Krasner’s fellow prosecutors, who are bent on restoring draconian minimums and limiting the discretion of judges to tailor the sentence to the offense.

The battle over minimum sentences reminds us that, when it comes to criminal justice reform, Philly today is an island of relative progress in a state that often disappoints reformers. Pennsylvania is known for bloated probation and parole caseloads, cumbersome court processing and pretrial incarceration that in some counties stretches for two years or more.

It is also the only state that provides no help to local public defenders. Franklin was long dead when the 14th Amendment guaranteed “due process” for all accused Americans, but his sympathies for the working poor would surely extend to indigent defendants.

In any case, Franklin would be gratified that his Jan. 17 birthday should be an occasion for drawing public attention to such uncomfortable questions. There is a remark attributed to Franklin, possibly apocryphal but suitable for an aphorism from Poor Richard’s Almanack: “Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are."

Bill Keller is editor-in-chief of The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization that covers the criminal justice system. On Jan. 18, The Marshall Project and Keller will receive the 2019 Franklin Founder Award. A free panel on criminal justice reform will be held in the morning, followed by a procession to Franklin’s grave and awards luncheon. For tickets: www.franklincelebration.org.