Defusing tense interactions in public spaces: Health-care experts weigh in | Opinion

For any public officials called upon to do social work, we believe their culture and training can benefit from these tips.

Kenny Solomon deserved better that rainy Tuesday night. As he sat quietly in his wheelchair in the concourse of Suburban Station on Feb. 12, he was loudly addressed by an approaching SEPTA police officer as “Dumb Dumb,” as in “Hey, Dumb Dumb!” and then “Let’s go, Dumb Dumb!” With one hand, the officer grabbed Mr. Solomon’s wheelchair and pulled him in reverse. Mr. Solomon’s only shoe dragged on the floor as he was whisked away, with his other foot looking swollen and wrapped in a gray hospital sock.

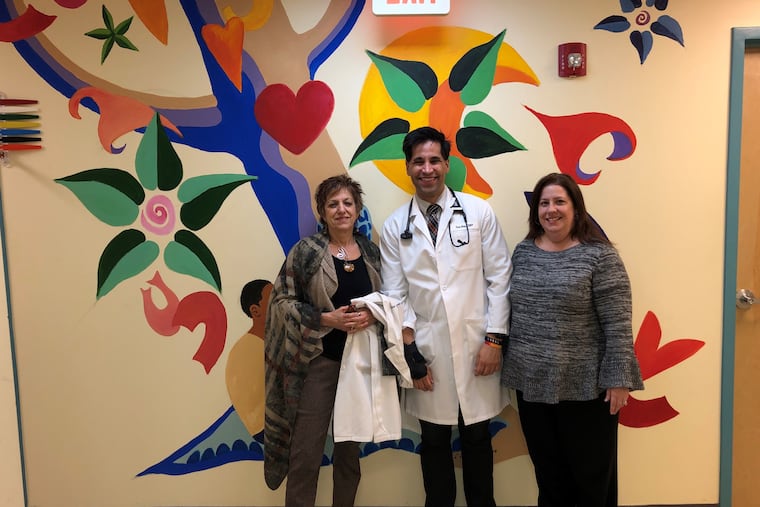

One of our nurse-practitioners at the Family Practice and Counseling Network, Tarik Khan, was in the station and recorded the incident while waiting for his train home. Since the incident, the responding officer has been reassigned to a different post awaiting the outcome of a SEPTA investigation.

As health-care professionals, we are familiar with the challenging issues that cause patients to experience homelessness and might bring them to seek refuge somewhere like Suburban Station. A 2010 report by the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that mental-health, substance-abuse, and medical issues are a common thread linking most people to homelessness. We have seen in our practice how burnout and a lack of training can cause staff to respond unprofessionally to the patients we serve. To prevent that dynamic, we offer extensive training and support for our staff as well as a strong emphasis on self-care.

Given the very difficult job the SEPTA police and all patrol officers face, they too deserve support and assistance. One such supportive action is the outreach workers who work with SEPTA police shifting their night schedules as of February, in part to connect more homeless people with social services.

For any public officials called upon to do social work, we believe their culture and training can benefit from the following:

Peer counseling to mitigate work stress. Like many of us, our police officers may suffer from a history of trauma: emotional, physical, or a history of childhood difficulty, or even PTSD. Stressors including those experienced at work can trigger or resurface past trauma, making it difficult to manage stressful situations. Trauma can also be acquired secondhand by experiencing repeated exposure to the stress of others. Counseling from behavioral health experts, and establishing a network of fellow officers trained in peer counseling, can relieve the effects.

Proactive measures to prevent officer burnout. An integrated mind-body therapist can offer officers other methods for offloading stress, including meditation and yoga. Our mind-body therapist has helped many of us deal with the aftermath of difficult situations.

Trauma-informed training. Performing your job in a trauma-informed way is akin to “universal precautions” used in medical settings. Medical personnel manage all patients as if any one of them might carry a bloodborne disease. In a trauma-informed approach, all individuals are approached as though they have a history of trauma and with an interest in “not what is wrong with them, but what has happened to them.” In our health centers, practitioners report that they can deliver more compassionate care to our patients when they recognize certain behaviors are often a result of deep trauma. Trauma-informed training can also prevent tense situations from escalating further. Since police officers are often asked, on top of their many other duties, to be in-the-moment social workers or give a medical response, it makes sense for them to train in this approach too.

Sensitivity training. We find the way Mr. Solomon was wheeled in reverse, pushed toward Tarik to make a point, and called “Dumb-Dumb” to be demeaning. Education geared toward a better understanding of the underlying causes of homelessness, and self-awareness of unconscious bias, can help us serve the needs of at-risk populations using tools we didn’t previously have, such as knowing how to properly escort someone in a wheelchair, and which terms belittle people with disabilities. Data have shown that programs to improve police interactions with vulnerable members of the public do significantly improve interactions and cut long-term costs.

We hope that SEPTA and other public safety leaders continue working to equip their officers so they can give our most at-risk Philadelphians — and themselves — their best.

Donna Torrisi is founder and current network executive director of the Family Practice and Counseling Network in Philadelphia, a nurse-led clinic network for the underserved in the U.S. and a division of Resources for Human Development Inc. Tarik S. Khan is a family nurse-practitioner at FPCN and helped to start the nonprofits Enabling Minds, which serves people with disabilities, and Project Affinity, which serves the homeless. Christine Masciarelli is a behavioral health consultant at FPCN with a degree in clinical social work.