Bobby Kennedy sought to unite the nation. Junior is part of an administration that sows division.

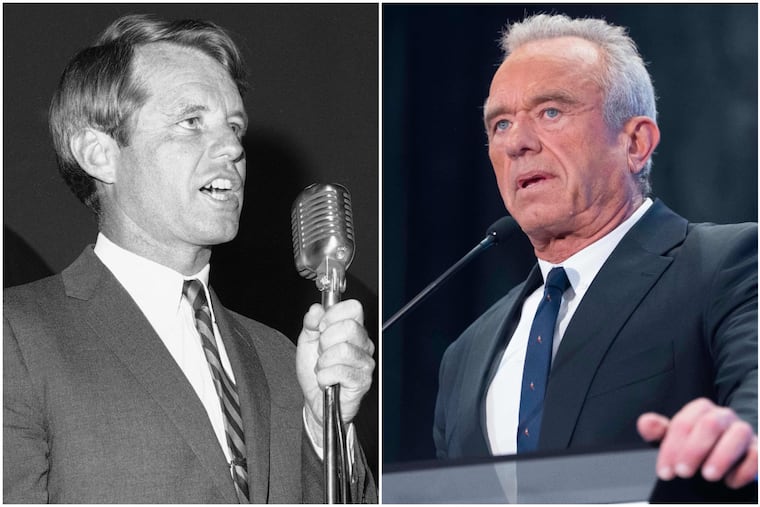

Considering the late Attorney General Robert Kennedy and his son together requires a leap of memory but a far larger one of faith, writes Chris Matthews.

I find it impossible, like many my age, to think of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. without thinking about his father.

It isn’t easy. Considering the late Attorney General Robert Kennedy and his son together requires a leap of memory but a far larger one of faith.

Bobby Kennedy sought unity. His son, the secretary of Health and Human Services, is part of the same Donald Trump team that sells national division on every possible front.

Americans of an older generation recall watching the funeral train back in 1968 that carried Sen. Robert F. Kennedy’s body from New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral to Washington, where he would join his brother already interred in Arlington Cemetery.

All along the tracks we saw the faces, white and Black, of working people for whom Bobby Kennedy held such promise. His presidential candidacy in 1968 meant an end to the brutal American conflict in Vietnam, an economic shift in our country’s wealth from the war in Southeast Asia to the dire needs of our major cities.

» READ MORE: 10,000 pages of records about Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 assassination are released, on Trump’s order

That June Saturday offered none of the pageantry of President Kennedy’s death five years earlier. There were no marching bands, no riderless cavalry horse, no President Charles de Gaulle or Haile Selassie, no heroic “Day of Drums.”

In Bobby’s case it was only about loss.

I can still feel the anguish in Frank Mankiewicz’s words making the sad announcement:

“Senator Robert Kennedy died at 1:44 this morning … June 6, 1968 … He was 42 years old.”

Kennedy had made his name as a U.S. attorney general fighting for civil rights. He took on Deep South governors to desegregate Ole Miss and the University of Alabama. He pushed his brother behind the scenes, to give the historic Civil Rights speech of 1963.

But what made him unique, as New York columnist Jack Newfield once wrote, was that he “felt the same empathy for white working men and women that he felt for Black, Latino, and Native American working men and women. He thought of police officers, waitresses, construction workers, and firefighters as his people.”

Bobby made a call for racial unity a part of his 1968 presidential campaign.

In the Indiana primary, he rode through the streets of Gary in an open convertible, Richard Hatcher (the city’s first African American mayor) on one side, Tony Zale, the middleweight boxing champ, so popular with the city’s white working people, on the other.

“I have an association with those who are less well off, where perhaps we can accomplish something: bringing the country together.

“I think we can end the divisions within the United States — whether it’s between Blacks and whites, between the poor and the more affluent, or between groups on the war in Vietnam. We can start to work together. We are a great country, an unselfish country. I intend to make that my basis for running,” Robert Kennedy said after winning the California Democratic Primary in 1968, minutes before his assassination.

And these were the very people who showed up for Bobby when his funeral train passed through Newark and Trenton and Philadelphia and Baltimore that grim Saturday in June.

Chris Matthews is the host of “Hardball” on Substack and the author of “Lessons from Bobby: Ten Reasons Robert F. Kennedy Still Matters.”