John Dunlap’s print shop in Old City deserves a blue historical marker — before this July 4

Few passersby stop to look at the tarnished, old plaque the Society of Professional Journalists placed on the building 50 years ago. Yet, it marks an important American Revolution site.

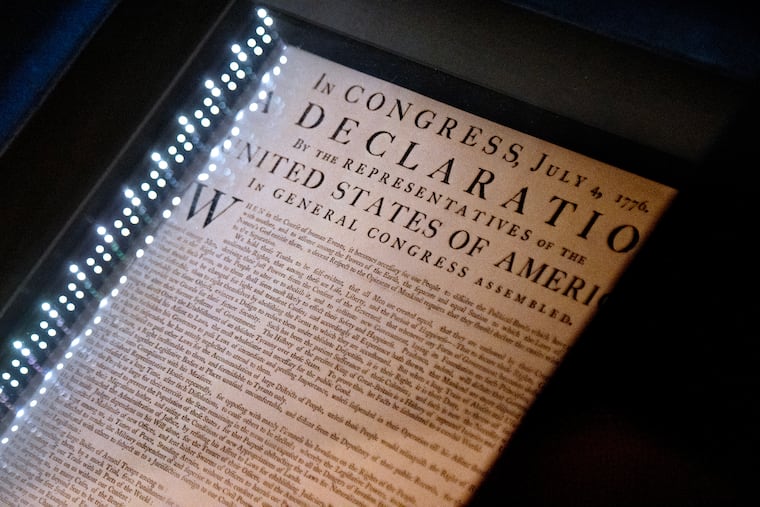

The most important printing job in American history took place in Philadelphia, on the corner of Second and High Streets, on the night of July 4, 1776.

There, in the shop of John Dunlap, the Declaration of Independence was first printed and sent around the new United States. Yet today, no Pennsylvania Historical Marker commemorates the spot on Market Street where the declaration first emerged to tell the world about the birth of a new country.

On the 250th anniversary of American independence, a marker should be erected as soon as possible by the city or state.

Dunlap’s job was of the first importance. Congress, led by the Boston merchant John Hancock, knew that getting word of independence out to the rest of the colonies was critical to gaining support at home for a war that was not going well. Since the war started in Lexington and Concord up in Massachusetts in April 1775, the Americans had forced the British out of Boston, but lost ground in New York. Independence was just as crucial for trying to get arms and money from Great Britain’s adversary, France, for George Washington’s poorly equipped Continental Army.

Sometime in the afternoon of July 4, Thomas Jefferson walked from the State House on Chestnut Street to the shop of Dunlap, a 29-year-old Irish immigrant and publisher of the Pennsylvania Packet. Jefferson handed Dunlap the original handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence, adopted just hours earlier by the Continental Congress, and ordered several hundred copies to be printed as soon as possible.

Working through the night, Dunlap and his assistants printed up at least two batches of “broadsides,” some on paper bearing the watermark of King George III. Dunlap had to rush, and some copies were printed slightly askew, while many were folded while still wet, leaving offset imprints.

They were rushed back to Congress and given to dispatch riders to distribute to colonial assemblies and the army. Washington received his on July 9 and had it read that day at his headquarters in Manhattan.

It took weeks for the other Dunlap broadsides to reach their destinations, the last arriving in Savannah, Ga., on Aug. 10.

One Dunlap broadside was used for the first public reading of the declaration, on July 8, in front of the State House, by Col. John Nixon. The scene was immortalized nearly a century later by Frederick Peter Rothermel, in a painting now hanging in the Union League Club.

To this day, no one knows how many were printed, but only 26 original Dunlap broadsides are known to exist, making them among the rarest of American artifacts.

The last one to come up for auction, in 2000, was bought for $8 million ($15 million in 2025 dollars) by the television producer and liberal activist Norman Lear. Most are held by museums or universities, but whenever they are displayed, the Dunlap broadsides draw crowds who are just as fascinated to see the words that declared a sovereign state as were those a quarter millennium ago.

Yet, few passersby, if any, stop to look at a tarnished, old plaque affixed to a rundown building at Market and Second. Put there 50 years ago by the Society of Professional Journalists, it is the only acknowledgment of one of the most important sites of the American Revolution.

Next to a shuttered diner, the plaque is likely all but ignored by any but the most dedicated history buff.

There is not enough time to go through the formal Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office process, but given the historic importance of the site, an ad hoc or special exemption by the city or state should be made, and a proper blue historical marker should be put up before July 4.

It is the least that can be done to commemorate a site where actions that still reverberate around the world took place.

Michael Auslin is a historian at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and is the author of the forthcoming “National Treasure: How the Declaration of Independence Made America.”