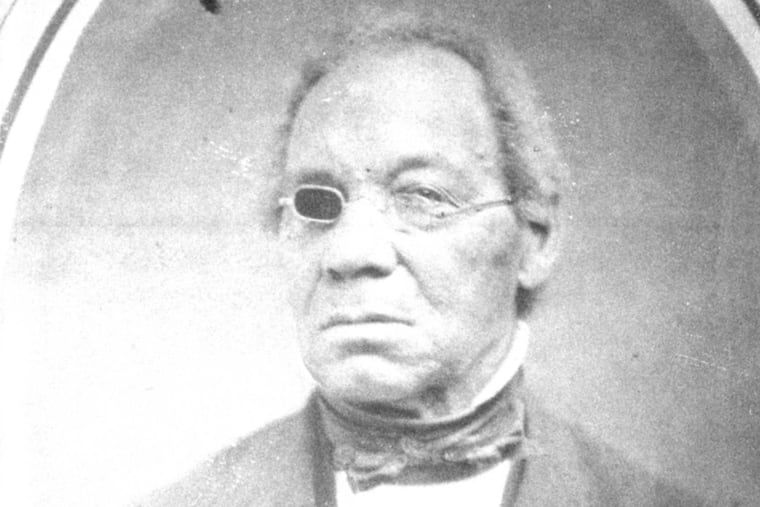

It’s time for Philadelphia to honor Stephen Smith, once the richest Black man in the U.S. | Opinion

Although he was born to an enslaved woman, Smith bought his freedom and became a wealthy businessman and generous philanthropist, who left his mark on Philadelphia for generations to come.

Philadelphia was home to many prominent figures in history. Some, such as Benjamin Franklin, have received widespread recognition. Others have not.

One of the “have nots” is Stephen Smith, a Black man who lived here between 1840 and 1873. Like Ben Franklin, Smith was accomplished in a variety of endeavors: He was a businessman, abolitionist, philanthropist, civic leader, and preacher. But unlike Franklin, he was born to an enslaved woman, which makes his life even more remarkable.

Stephen Smith was born around 1795 in Dauphin County, Pa. He was sold at a young age and was taken to Columbia, Pa. His mother, Nancy Smith, escaped to rescue him and was pursued by the woman who owned her. When her owner tried to forcibly remove her, Stephen’s new owner, along with some Columbia residents, stood with Nancy, and she stayed with her son. This event galvanized the region and is considered by some historians to be a turning point in the start of the Underground Railroad. It also had a profound effect on the young Smith.

Over time, Smith became a wealthy businessman and generous philanthropist, who left his mark on Philadelphia for generations. The city should recognize his legacy.

When Smith turned 21, he borrowed $50 to purchase his freedom, and married Harriet Lee, who worked as a servant in someone’s home. He then went into business for himself in Columbia, putting into practice what he learned about the lumber business from his owner. Over the next several years, Smith expanded his business holdings to include real estate and stock in the Columbia Bank & Bridge Co., which was responsible for constructing a major bridge across the Susquehanna River. As the largest stockholder, he was entitled to be the president of the company but was prevented from assuming this position because he was Black.

During his lifetime, Smith was recognized as the richest Black man in America. Some people didn’t like that.

“During his lifetime, Smith was recognized as the richest Black man in America.”

In 1834, he was the target of a white mob that vandalized his office, demanded that he sell his business assets, and attacked Black people living in Columbia. After initially putting his business holdings up for sale, Smith retracted his offer when no one came forward to purchase them.

By 1840, Smith acquired a business partner, William Whipper, who was also Black. He started to sell coal and moved to Philadelphia, where he established the eastern location of their joint business. They owned 22 railcars that carried lumber throughout Pennsylvania, which had secret compartments that were also used to move fugitive enslaved people, at great risk to everyone involved.

Stephen and Harriet hosted notable people of their day at their Philadelphia home at 921 Lombard St., including Frederick Douglass and John Brown, who sought his counsel and funding. He built a vacation home in Cape May, which still stands today and is part of the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Stephen Smith was a representative to the Colored Convention movement, and he liberally funded projects to enhance the lives of the city’s Black residents, including churches, an extension to the Institute for Colored Youth, and a new Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Persons. (Today, the Stephen Smith Home for the Aged is located just steps away at 44th and Girard.) Even though one public hall Smith built for Black people was burned down by rioters in 1842, he was not discouraged from his civic endeavors.

Stephen Smith’s life stands as a testament to the power of intelligence, moral guidance, and perseverance to advance civic advocacy, while developing varied business interests. It is for this reason that I coauthored an application to the Philadelphia Historical Commission to designate the houses at 919-921 Lombard as historic and list them on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. In a city that prides itself on its rich history, it is critical that Stephen Smith’s legacy is remembered by preserving his home and that of William Whipper, who lived next door.

Philadelphia residents owe a lot to Smith and his life’s work. He formulated ideas that were the foundation for plans he executed for not only his own benefit but that of his community.

During Black History Month, we should learn more about Stephen Smith and other key historic figures we don’t hear as much about, but whose actions and achievements shaped the history of our country.

Michael Clemmons is a docent at the African American Museum in Philadelphia and a founding member of the Black Docents Collective.