We speak of ‘terraforming’ distant planets while tolerating a world where basic habitability is a privilege

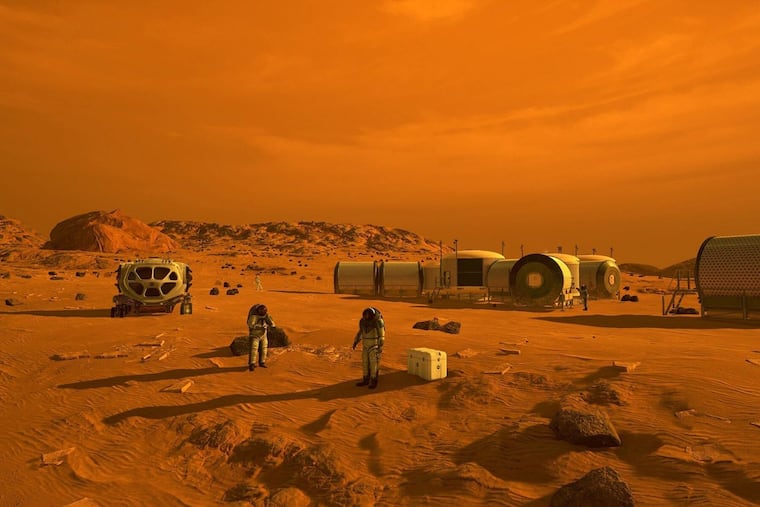

When scientists discuss making Mars livable, they describe creating conditions many humans have never experienced on Earth: stable temperatures, clean air, reliable water access, fertile soil.

While the Poconos experienced another week of 88-degree temperatures this summer — comfortable by today’s global standards — the Environmental Protection Agency quietly drafted plans to eliminate the scientific finding that greenhouse gas emissions threaten human life through dangerous planetary warming.

The timing felt surreal, like watching an arsonist standing safely outside a burning building, methodically destroying the blueprints that could guide firefighters. It crystallized a troubling paradox: Scientists often speak about the possibility of “terraforming” distant planets, or changing their atmospheres and other conditions to make them more like Earth, while tolerating a world where basic habitability is a privilege for billions already here.

When scientists discuss making Mars livable, they describe creating conditions many humans have never experienced on Earth: stable temperatures, clean air, reliable water access, fertile soil for food. The technical specifications for terraforming read like a wish list that vast populations could only dream of accessing.

Meanwhile, billionaires burn massive quantities of fossil fuel launching rockets toward cosmic escape routes. Jeff Bezos thanked Amazon customers for funding his space tourism, the same customers whose warehouse colleagues endure dangerous heat without adequate cooling.

This isn’t a critique of space exploration; it’s an observation about priorities when we engineer exit strategies for the wealthy while the majority lack entry into basic habitability.

This isn’t accidental geography, it’s engineered inequality.

To be sure, we’re a long way from having the technological capacity to terraform other planets, but the topic is no longer considered something that should be confined to the realm of science fiction. (Longtime sci-fi fans may remember that colonists in the 1986 James Cameron film Aliens were part of mission to terraform a faraway planet.)

That said, it is a bitter irony that an ad hoc version of terraforming has already happened here. We’ve engineered pockets of perfect climate control in affluent neighborhoods, office buildings, and shopping centers — carefully controlled ecosystems where temperature and air quality are precisely managed. Yet step outside these climate-controlled enclaves, and survival during extreme weather becomes an economic lottery.

Urban heat islands push temperatures 10-15 degrees higher in low-income neighborhoods with fewer trees and more concrete. Farmworkers labor in fields where heat stress kills dozens annually. Elderly residents in poorly insulated apartments become casualties of heat waves.

As a master’s of public health student studying environmental health, I’ve learned that climate isn’t just about global averages, it’s about who bears the burden of atmospheric change and who benefits from atmospheric control. Heat mortality data reveal how extreme temperatures disproportionately affect communities with the least access to cooling and most exposure to heat-trapping infrastructure. This isn’t accidental geography, it’s engineered inequality.

The EPA’s proposed elimination of guidelines about greenhouse gases would banish foundational climate science while communities across the Global South face temperatures that regularly exceed human thermal tolerance.

Removing the EPA guidelines is like forcing firefighters to burn down their own stations while the city burns around them.

The same species that hopes to one day be capable of engineering entire planetary atmospheres already possesses sophisticated climate modeling that can project atmospheric conditions centuries into the future — detailed enough to guide theoretical planetary engineering. Yet this scientific capacity becomes politically inconvenient when applied to our current planetary emergency.

Here in Monroe County, we don’t typically experience heat waves like those in regions that are regularly facing deadly temperatures. But our comfort doesn’t insulate us from the moral implications of our terraforming priorities.

When we fund rockets to Mars while defunding climate science on Earth, when we perfect life support systems for space travel while communities lack basic cooling centers, we’re demonstrating remarkable capacity to engineer livable worlds — we’re just choosing to do it selectively.

The ambition exists. The knowledge exists. The engineering capacity that could one day terraform Mars could certainly air-condition schools in Phoenix, create cooling corridors in urban heat islands, and transition energy systems away from the greenhouse gases driving this crisis.

What’s missing isn’t just technical capability — it’s moral imagination and policy priorities that center human health equity.

Perhaps the most honest conversation isn’t about terraforming distant planets, but about completing the terraforming of this one — making it genuinely habitable for all of its current residents rather than engineering escape routes for the few who can afford to leave.

As Pennsylvania residents, we have both the privilege and responsibility to demand better. Our congressional representatives must reject efforts to undermine climate science and instead support policies that extend terraformed protection to everyone, not just those who can afford it.

The rockets keep launching. The planet keeps warming. And somewhere, in a region experiencing temperatures we can barely imagine, someone is asking not about making Mars livable, but about making Earth survivable for one more day.

Pragya Thakur is a national board-certified health & wellness coach and MPH candidate at Boston University, focused on environmental health and policy. She lives in Arlington Heights, Pa.