New anti-birth control policy at USciences is unfair to students who didn’t choose a religious college

As the nurse at the student health office, I sometimes gave out hundreds of condoms per week and counseled students with unwanted pregnancies. This was part of my job as a health-care provider.

I worked in the student health office of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia for more than 30 years, from 1976 to 2012.

I was very sad to learn that, because of its merger with St. Joseph’s University, a Catholic school, USciences announced it will no longer dispense birth control.

» READ MORE: USciences’ health center will no longer dispense birth control once it merges with St. Joe’s

For many years, I was the only full-time health professional at the student health office. And distributing contraception was part of what I did.

Starting in the late 1990s, as the student body was shifting from a largely conservative, male campus to one that included more women, I began leaving out bowls of free condoms in the waiting room. I heard some complaints from administrators, but never received a formal request to stop, so I continued. I believed then — and still do — that giving out free condoms was better than dealing with unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases.

And the students didn’t complain, either. Quite the opposite — the bowl probably held 150 condoms, and I had to refill it several times per week.

Our office didn’t have an official gynecology service, but as our demographics kept changing, we provided more gynecology and birth control services. Some doctors from Thomas Jefferson would come for a few hours per week to examine patients, and I left free brochures in the waiting room that covered topics such as STDs, safe sex, and HIV. Roughly once per month, I met with different students who needed help with an unwanted pregnancy. I didn’t hesitate to discuss all of their options, including abortion, and referred them to Planned Parenthood.

“Roughly once per month, I met with a female student who needed help with an unwanted pregnancy.”

When I was working there, all of the health services we provided were free to students. I didn’t question any of my decisions to educate and discuss birth control with students. USciences was the first college of pharmacy in North America, and family planning is part of health care, pure and simple.

So when I read that, because of the merger with St. Joe’s, USciences told students it would no longer provide birth control to students, I felt so sad. I understand that some Catholic students prefer to attend a university that aligns with their values, like St. Joe’s, whose student health center also does not dispense birth control. But the students at USciences didn’t make that choice. They enrolled in a university for careers in science and health care — and now they were told they would be denied essential aspects of health care for themselves.

I’m concerned about what might happen to USciences students. If they have questions about birth control, need access to contraception, or have an unwanted pregnancy, this merger makes an already hard situation that much harder. Where will they go now?

This is not the only instance when mergers have left patients with fewer services. When hospitals merge with Catholic health-care facilities, they often lose the ability to perform abortions, sterilizations, and assisted reproduction; they may not be able to offer rape victims the “morning-after pill” to prevent pregnancy. Roughly 10 years ago, Abington Hospital called off a proposed merger with Holy Redeemer after 150 Abington doctors protested the plan to stop performing abortions.

People have every right to choose services that align with their values — whether in universities or at hospitals. Students at St. Joe’s were allowed to make that choice, and current USciences students should be as well.

The part of the university that remains USciences should continue to offer contraception and family planning services for the time being — at least a year — or contract with an outside provider to ensure that students have a place to go off campus where they can continue to receive this vital part of health care.

Anything less is simply unfair.

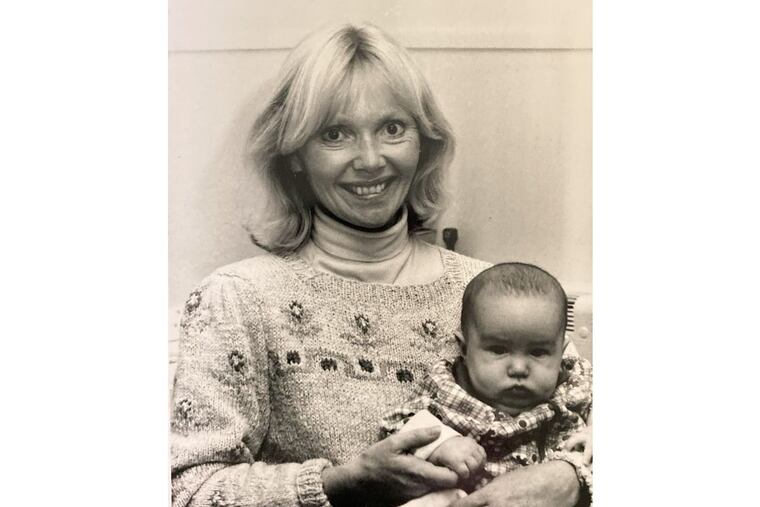

Bonnie Brigham Packer is a retired nurse who lives in Wenonah, N.J.