We need to make sure our history isn’t history | Editorial

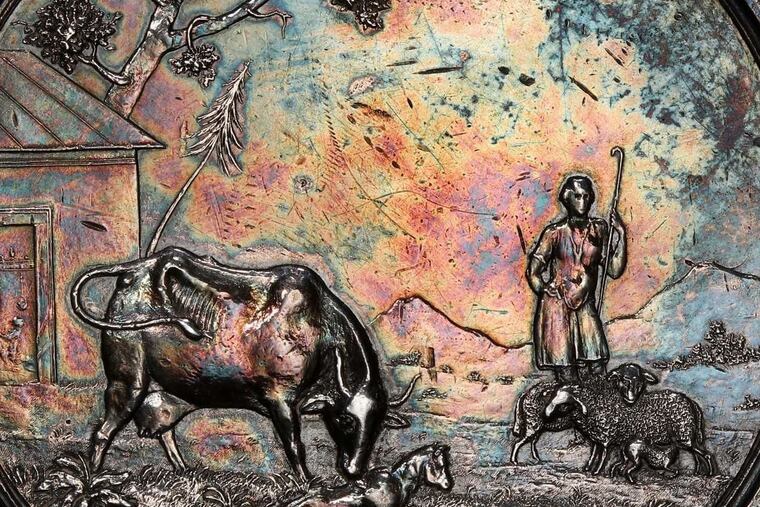

Strapped for cash, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania sold a collection of commemorative medals at auction for $2.2 million. It's not the first time a lack of cash has led to sales of our history.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania realized $2.2 million last November by selling 1,102 commemorative medals from a collection bequeathed to it in 1897. The financial struggles of this nonprofit institution in Center City are worrisome but all too familiar. In 2018, the Philadelphia History Museum abruptly shut down. While it will be rebooted through a partnership with Drexel University, neither the Historical Society’s proposed affiliation with the University of Pennsylvania nor with Drexel has borne fruit.

HSP calls itself “Philadelphia’s Library of American History” with good reason: It is home to a printer’s proof of the Declaration of Independence, a first draft of the Constitution, a journal of the Underground Railroad, and millions of other handwritten, printed, and engraved materials.

Selling commemorative medals said by society officials to be of marginal scholarly and public interest was at best a stopgap measure. Last year, the Historical Society, founded in 1824, laid off one-third of the employees on a staff described as already bare-bones.

This suggests a broader, deeper, community-driven effort is needed to strengthen this institution. The society is part of an ecosystem of institutions, including the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, that support the city’s status as a global center for historical research. They are stewards of a legacy that belongs to us all.

History is essentially the city’s brand, one that attracts millions to visit. But history is more than a story or guides dressed up in Colonial costumes. History lives in the documents, objects, and artifacts collected over the years — all of which constitute an inheritance that needs constant care and feeding. And that takes money.

The past few years have not been kind. In 2011, for example, the Philadelphia History Museum sold off some of its artifacts and paintings to cover a construction loan. In 2018, the museum shut its doors and eventually entered into an agreement with Drexel University.

HSP’s dispersal of the medals at a Nov. 16 auction in Baltimore was not widely known until a story last week by Inquirer reporter Stephan Salisbury. The decision to sell struck some critics as needlessly secretive and unlikely to inspire confidence. A statement posted on the HSP website insisted that the decision to deaccession the medals was in line with the institutional mission honed decades ago when the society board voted to no longer collect objects but to focus on curating its archives. HSP management says they have no plans to sell any of its core collections.

That’s good news. But it would be better if more of the goals HSP outlined in the 2016 “Strategic Vision and Business Plan” were achieved: to become an active catalyst and gathering place for a broad, ongoing discussion not only about the past but the future. That will require more work, support, and, yes, more money. That money must come from more than a few donors. The city and the state — administering taxpayer dollars — should be at the table to help find a longer-term solution. Without figuring that out, it’s not only the past that disappears … it will also be the things and ideas that we ourselves hope to leave behind.