William McSwain, drop the supervised injection site lawsuit and let Philly save lives | Editorial

The supervised injection site debate shows that the U.S. has come a long way. But in other ways, we are still in 1986.

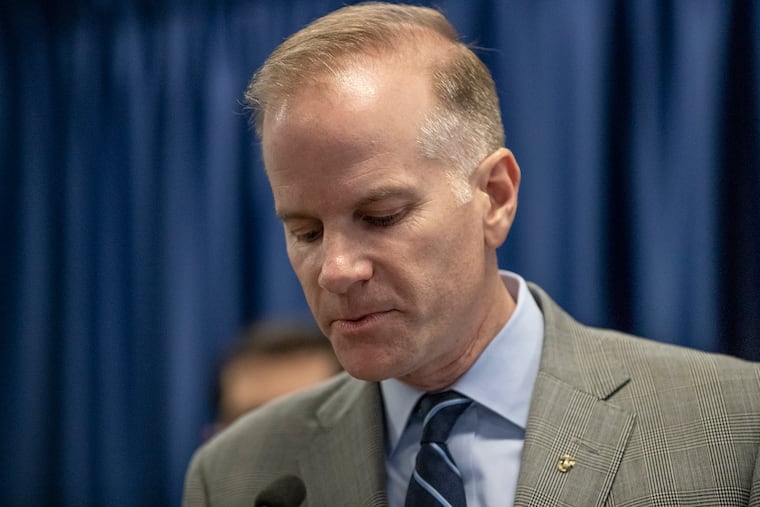

Last week, U.S. District Judge Gerald A. McHugh heard oral arguments in the case of U. S. A v. Safehouse, the attempt by U.S. Attorney William McSwain to stop the Philadelphia nonprofit from opening a supervised injection site. The scope of the hearing was limited to the legality of the sites under current federal law and not their merits or ability to save lives.

According to McSwain, a supervised injection site would violate the “crack house statue” — an addition to the Controlled Substances Act from 1986. The law, championed by then-Sen. Joe Biden, made it illegal to own or manage a property to use, produce, or sell illegal drugs. Safehouse argued that the law was not intended to cover a public health intervention.

Instead of launching a public health campaign during the crack epidemic, the U.S. launched the War on Drugs — and on black communities. We are still paying for that mistake with mass incarceration, trauma, and further entrenched poverty.

The supervised injection site debate shows that the U.S. has come a long way — partly because of the death toll of the opioid crisis, and partly because of the race of majority of those dying. But in other ways, we are still in 1986: arguing that a measure to save lives is just like a criminal enterprise to sell drugs.

As we await the judge’s ruling, it’s worth remembering that there is another option: McSwain could drop the lawsuit.

Several times during the hearing, exchanges between McSwain and McHugh highlighted the absurdity of McSwain’s literal reading of the law.

At one point, the judge posed a hypothetical to McSwain: A parent of an adult child addicted to opioids asks the child to move in and says, “We don’t want you to use but if you are going to use we want you to use right here, in our presence, and we got Narcan.” Would the parents violate the law in the way McSwain argues Safehouse does? McSwain responded, “I think it wouldn’t.”

What is the difference between a parent telling their adult child to inject at home in their presence and a parent telling adult child to inject at Safehouse in the presence of a medical professional?

In another instance, McSwain argued that a mobile supervised injection site operating out of a van would not violate the law as long no one actually entered the vehicle — though Safehouse workers could give out injection equipment and observe people injecting.

Is McSwain really advocating for more public injection, one of the biggest complaints of Kensington residents, as an overdose death prevention strategy?

McSwain was not elected by a single Philadelphian but appointed by a president who was the choice of very few in the city. Yet, he is attempting to block a public health intervention that is supported by the mayor.

It is time for the U.S. Attorney’s Office to start participating in the Philadelphia community instead of battling it. The first step is to drop the lawsuit against Safehouse — and to continue to prosecute cases that bring justice, not just literal interpretations of the law that do not serve its constituents.