Why did child porn come up in the Supreme Court confirmation hearings? | Opinion

Hint: It has to do with QAnon conspiracies. Three professors weigh in.

At last week’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson, various Senate Republicans made references to child pornography. We asked three scholars — sociologist Sarah Louise MacMillen at Duquesne University, political scientist Caitlin M. Brown at Bryn Mawr College, and historian Lara Putnam at the University of Pittsburgh — to help us make sense of it.

We heard a lot during the confirmation hearings from senators referencing child pornography. What was that all about?

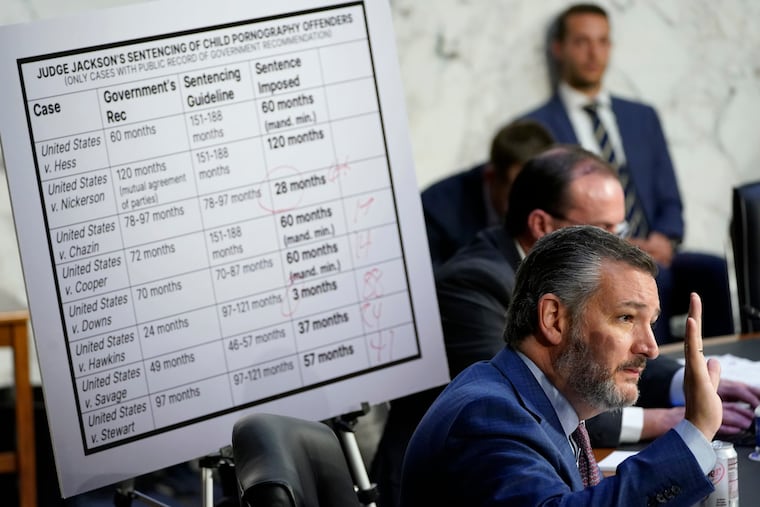

Brown: In an effort to raise doubt about the fitness of Judge Jackson, some Republicans — notably Sens. [Josh] Hawley, [Mike] Lee, [Ted] Cruz, [Marsha] Blackburn, [Lindsey] Graham, and [Tom] Cotton — seized upon her sentencing record in cases involving child pornography. They accused her of being more sympathetic of child predators than their victims, noting that she has frequently issued sentences that do not, or just barely, meet minimal sentencing guidelines. What they have omitted in these accusations is how common it is for federal judges to deviate from sentencing guidelines, especially in cases where the offender views or distributes pornographic material but does not produce it. This line of attack serves as a dog whistle for followers of the QAnon movement.

MacMillen: Child sex abuse is seen as the ultimate perverse attack on innocence, and an obsession with purity and innocence is one hallmark indicator of a religiously driven politics of false nostalgia. A “cue” to the QAnon folks is to highlight the link of sexual abuse to the “liberal social order” — and a general sense of liberal perversion.

Putnam: There is a long history of politicians accusing opponents of being weak on crime. But the repeated and high-profile focus on child pornography, in particular, is not simply that: No concerns over these particular sentencing decisions were raised, for instance, in Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearings to the federal appeals court just last year. Rather, it is part of what Georgetown University professor Donald Moynihan has labeled the “QAnoning of our political discourse” — the surge in Republican politicians’ and activists’ use of language that frames Democratic positions on issues from civil rights protections for trans people to diversity and inclusion in education as actively and intentionally promoting the sexual abuse of children.

Can you help us understand a bit more about the connection between QAnon and this kind of conspiracy theory?

Brown: To suggest that Judge Jackson is sympathetic to child predators is to situate her within the alternate reality imagined by the QAnon conspiracy movement. QAnon claims that the world is run by a secret Democratic cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles. Criticizing Judge Jackson’s handling of cases involving child pornography is not merely an indictment of her morality; it is a suggestion that she is part of, or is doing the bidding of, that secret cabal. The senators attacking Judge Jackson with these spurious accusations are, in the process, saying that they recognize the QAnon conspiracy movement.

MacMillen: A politics of extremism and paranoia is, in part, a response to a perceived threat. These discourses existed before the “official” emergence of QAnon, but they are taken even further today. Pockets of the extreme Christian right view trends like secularization and ethnic/racial diversification negatively, also fearing “the Great Replacement” (see the recent work of Robert Pape, University of Chicago, on Jan. 6 insurrectionists). QAnon sees a “crisis” to be addressed and a threat to the “Christian” order of existence.

Putnam: The QAnon conspiracy theory holds that a battle is underway against powerful pedophiles who they believe dominate Hollywood and the Democratic Party. At the University of Pittsburgh’s Pitt Disinformation Lab, we have tracked how these beliefs moved from fringes to the center of political discussion over the course of spring and summer 2020, appearing in nominally nonpolitical Facebook groups in our region, entwined with COVID-denialism and anger over pandemic restrictions. Angry references to Joe Biden as a “pedo” or “child sniffer” became commonplace.

Several years after the Pizzagate episode, we might think these theories would be debunked. Why have they continued to take hold?

Brown: For some Americans, a world in which a Black woman could become a Supreme Court justice, following on the heels of a Black president and a near-win by a female candidate, is a world-out-of-place. Therefore, it no longer seems fantastical to imagine that Democratic elites are worshipping Satan while molesting, killing, and, in some instances, eating children. But I also think these conspiracy theories are part of an effort to put the world back into place. They tap into what some Americans “know” is true — that women and people of color are not only unfit to hold positions of authority but also that allowing them to have power is a direct threat to the American way of life. If pedophilia is the societal scourge, then we need a state composed of white men playing the role that has been historically assigned to them — that of the protective father.

MacMillen: I think in some ways the COVID pandemic and the closures of church buildings drove people in radical traditionalist and evangelical Christian communities to the internet for religious information, authority, and community. Technology could feed this psychological state of paranoia, with easily accessible QAnon material online. More educated members of the community could not confront conspiratorial logics face to face.

Putnam: Both domestic and international political actors have strong incentives to keep strengthening the leverage QAnon provides. Notably, when President [Donald] Trump was asked in a televised town hall in October 2020 to denounce QAnon, he declined to, instead adopting QAnon adherents’ own framing: “I do know they are very much against pedophilia. They fight it very hard, but I know nothing about it.”

Another beneficiary of the networks of distrust that QAnon has fostered is Vladimir Putin. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, content identifying Putin as an ally in the struggle against the “Cabal” of pedophiles has redoubled in QAnon discussion spaces.

In an apolitical sense, what is the best way to respond to, debunk, or address this kind of misinformation and disinformation?

Brown: For many adherents, a pushback from the powers-that-be is a sign that their theories are true. It’s important that former adherents and leaders within a conspiracy theory movement speak out against them, as they are more likely to be trusted. To combat mis- and disinformation more generally, the mainstream news should resist the urge to present it as one side’s considered opinion or good-faith contribution to the public debate. Instead, the factual inaccuracies and political purpose of it should be clearly spelled out in reporting.

MacMillen: I will speak to this as an educator in religion and as a person of faith. Christians have a responsibility to confront these narratives within their own communities. Unfortunately, non-Christians can’t do anything to address it: They are not in the same “discourse community.” QAnon followers probably wouldn’t listen to anything “secular” or “liberal.”

The obstacle here is twofold: 1) QAnon’s virulent anti-intellectualism, and 2) QAnon sees the world as woefully fallen, rather than full of God’s grace. From this point of view, the line of reasoning goes something like this: “If the political realm is fallen, why should we trust this ‘rigged’ system?” QAnon’s theology presents an anti-political attitude, calling for an apocalyptic political rupture.

Putnam: Part of what is tragic here is that we are in the midst of a genuine crisis in children’s exposure to sexual predation — a fact that is surely part of what makes the fears QAnon exploits so vivid and widespread. And yet the kind of posturing we saw in the Senate Judiciary Committee last week does nothing to address it.

The real issue is that cell phones, internet access, and social media platforms have combined to radically expand opportunities for child sexual predation. I wrote in Wired this month about my experience discovering dozens of public Facebook groups with tens of thousands of members that explicitly target preadolescent children for intimate contact.

A real response to QAnon’s sway would encompass not only the tech platforms that speed disinformation but also the politicians that benefit from it. It would also address the genuine trauma and fears of this historical moment: a moment in which neither the smartphone in your child’s hand nor the coaches, team doctors, priests, or relatives around you may feel trustworthy.

Sarah Louise MacMillen is an associate professor of sociology and the director of the Peace, Justice and Conflict Resolution Minor Program at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Her research focuses on sociology of religion and social theory.

Caitlin M. Brown is currently a visiting assistant professor of political science at Bryn Mawr College. Her areas of interest and expertise include gender politics and social movements.

Lara Putnam is the UCIS research professor in the department of history at the University of Pittsburgh and the colead of the Southwest PA Civic Resilience Initiative at the Pitt Disinformation Lab. @lara_putnam