What if the 1981 strike hadn’t interrupted the Phillies’ World Series title defense?

The defending-champion Phils were in first place when the 1981 strike began. Once the season restarted, they never regained their momentum.

We don’t know when baseball will begin in 2020, or if a season will even be played. The Phillies should have started the season on March 26. Instead, we’re left wondering how Joe Girardi would have impacted this team, or how Zack Wheeler’s fastball would have looked, or how many home runs Bryce Harper could have hit. All we have are what-ifs. So during the shutdown, we’ll take a look at some what-ifs that could have changed the course of Phillies history.

One in an occasional series.

History shows that the Phillies’ first reign as World Series champions lasted for 355 days and ended on Oct. 11, 1981, with a shutout loss to the Montreal Expos in Game 5 of the National League Division Series.

Larry Bowa knows better.

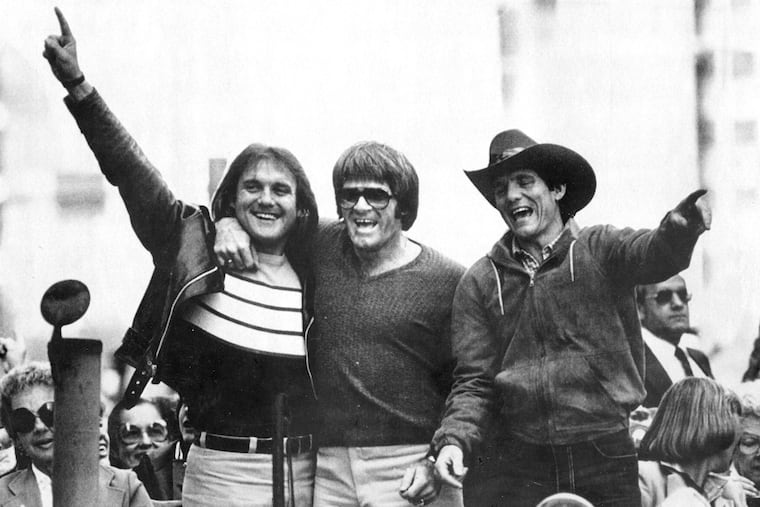

For practical purposes, the Phillies’ title defense ended four months earlier. When they walked off the turf at Veterans Stadium on June 10, 1981, after rallying from a four-run deficit to defeat the Houston Astros, 5-4, in a Steve Carlton-Nolan Ryan duel in which Pete Rose tied Stan Musial’s NL record of 3,630 career hits, they were in first place with a 34-21 record. They had won five consecutive games, nine of 11, and 16 of 25, and seemed to be humming right along.

But two months would pass before they returned to the field. A players’ strike interrupted the season and vaporized the Phillies’ mojo. They never got it back. Not even during a postseason that was expanded from four teams to eight.

To some, then, the 1981 season represents one of the biggest “what-ifs” in franchise history: If the strike hadn’t happened, would the Phillies have repeated as World Series champs, a feat that hasn’t been accomplished by an NL team since Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine” won it all in 1975-76?

“That question looms over my head a lot, man,” said Bowa, then the Phillies’ shortstop. “I think about that a lot. Getting out of the gate, basically right before the strike, we were playing real good. I envisioned us doing it again. But it didn’t materialize.”

There were several reasons for that. Chief among them: A lack of motivation.

Once the strike ended, MLB decided to split the season into halves and add an extra round of playoffs. Teams that were in first place at the time of the stoppage were guaranteed entry into a best-of-five division series against the second-half winners. The Phillies, therefore, didn’t have much to play for once games resumed.

As left fielder Gary Matthews put it in a 2009 interview: “We lost our giddy-up-and-go.”

The Phillies lost seven of their first nine games in the second half, didn’t win more than four games in a row, and finished 25-27, the third-best second-half mark in the NL East behind the Expos (30-23) and St. Louis Cardinals (29-23).

But at least the Phillies had the first half to fall back on. In the NL West, the Reds won the most games overall (66). But because they didn’t win either half, they didn’t make the playoffs.

At the time, and certainly with the benefit of hindsight, Bowa wished the playoff format had been different.

“We were under the impression that it was going to be two halves, but if you won the second half, you don’t have to worry about a [first-round] playoff,” Bowa said. “Before we started up the second half, they said, no matter what you do, you’re going to have to play somebody. Mentally, I think that affected our team. We went out there and played hard, but mentally we knew it didn’t matter. We could’ve won every game the second half. We were going to have to play somebody.”

Even hard-driving manager Dallas Green couldn’t break the players of that mindset. Not that he didn’t try. Green benched catcher Bob Boone and center fielder Garry Maddox for lengthy stretches of the second half in favor of Keith Moreland and Lonnie Smith, respectively. He called up Mark Davis and Dickie Noles from triple-A Oklahoma City and put them in the starting rotation.

But the Phillies either tuned out Green or stopped responding to tactics that were effective the previous year.

“I just don’t think a manager can whip a team to the finish line,” Boone told the Inquirer in 2009.

There were other issues, too. Most Phillies players decided to stay in the area and work out at local high schools during the strike. But they couldn’t simulate game conditions. Several players, particularly pitchers, weren’t physically up to the challenge of picking up a season 50 days after it was halted.

Marty Bystrom, for example, didn’t throw during the strike because of a sore shoulder. He was unable to crank his arm up again and got shipped out to double-A.

“I went out and threw batting practice and simulated a couple innings, and my shoulder was hurting again,” said Bystrom, who went 5-0 with a 1.50 ERA as a September call-up in 1980. “They weren’t very happy with me, or Dallas wasn’t anyway, and when they got to the postseason, he didn’t put me on the roster. It was much deserved. It was just bad judgment on my part, and if I could do it all over again, I would certainly do it differently.”

Green, meanwhile, received permission during the strike to talk to the Chicago Cubs about taking over as their general manager after the ’81 season. Phillies owner Ruly Carpenter, frustrated by the escalation of player salaries, decided to put the team up for sale.

Amid that backdrop, the Phillies lost the first two games of the division series in Montreal, both by 3-1 margins. They won Game 3 at home, 6-2, then pulled out a 6-5 thriller in Game 4 on George Vukovich’s walk-off homer against Expos closer Jeff Reardon in the 10th inning.

Even then, a banner across the top of the next day’s Inquirer read, “Why Dallas Green wants to leave the Phils”.

"We felt good," Bowa said. "We had Carlton going. They had Steve Rogers, who was like a pain in our butt. He knew how to pitch. We knew it was going to be a tough game, but we had confidence."

The Expos got to Carlton for two runs in the fifth inning and one in the sixth. The Phillies got only six hits -- all singles -- against Rogers, and that was it.

“We were robbed of everything we had going for us in the first half,” Green told reporters after the game. “We lost those 50 games, and as a result, we lost 1981.”

Within days, Green was introduced as the Cubs’ general manager. A few weeks later, Carpenter sold the Phillies to a group led by club president Bill Giles for $30.175 million. Bowa, embroiled in a contract squabble with Giles after being promised an extension by Carpenter, got traded to the Cubs (with a prospect named Ryne Sandberg) in the offseason.

Maybe all of those things still would have happened if the Phillies had defended their crown.

Then again ...

“I thought we could’ve had a total of three [World Series championships] during that run,” said Bowa, who points to 1977 and 1981, specifically, as missed opportunities. “I think the strike had a big impact on us. I really do. There’s no doubt in my mind, we keep playing and don’t have a strike, in my opinion, we might be going to the World Series again.”