What if the Phillies hadn’t traded Ferguson Jenkins in 1966?

By any measure, Jenkins ranked with the best pitchers in baseball in the late ’60s and through the 1970s. To the Phillies, though, he will forever embody a big, huge, enormous ... blunder.

We don’t know when baseball will begin in 2020, or if a season will even be played. The Phillies should have started the season on March 26. Instead, we’re left wondering how Joe Girardi would have impacted this team, or how Zack Wheeler’s fastball would have looked, or how many home runs Bryce Harper could have hit. All we have are what-ifs. So during the shutdown, we’ll take a look at some what-ifs that could have changed the course of Phillies history.

Second in an occasional series.

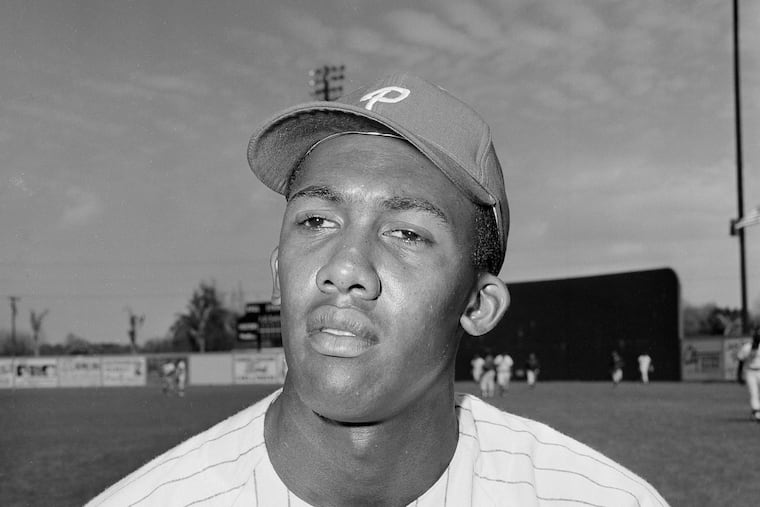

Based on how well he pitched after getting called up late in the 1965 season, Fergie Jenkins just assumed he had made a positive first impression on the Phillies.

Maybe that’s why, upon getting traded early in 1966, he became so consumed with leaving a lasting one.

Jenkins won 284 games in a major-league career that spanned 19 seasons. He captured the National League Cy Young Award in 1971 and was runner-up in 1967 and 1974. He got elected to the Hall of Fame in 1991. By any measure, he ranked with the best pitchers in baseball in the late ’60s and through the 1970s.

To the Phillies, though, Jenkins will forever embody a big, huge, enormous ... blunder.

Imagine how franchise history might have been altered if Jenkins hadn’t been included in the five-player swap that netted veteran right-handers Larry Jackson and Bob Buhl from the Chicago Cubs. Think of the possibilities if the Phillies had paired young, emerging Jenkins with older, still ace-worthy Jim Bunning in 1966 and ’67. Or the righty-lefty combination that could have existed atop the rotation in the ’70s if Jenkins had been able to team up with Steve Carlton.

“When I got traded, [pitching coach] Cal McLish kind of pleaded my case and said, ‘Don’t trade Jenkins,' " Jenkins recalled in an interview last year. “But [then-manager Gene] Mauch just got rid of young guys. He was a veteran-type manager that wanted guys that had more experience than myself and the other young pitchers, so a lot of us got traded away."

Mauch’s preference for older pitchers was never more pronounced than in the years that followed the Phillies’ epic collapse in 1964. As the ’66 season opened, they had Bunning (34 years old) and Chris Short (29) ticketed for the starting rotation. But although general manager John Quinn tried hard to acquire another veteran starter, the next-best option was 24-year-old Ray Culp, a holdover from ’64 who never seemed to engender Mauch’s faith.

Still, Jenkins was secure about his standing with the Phillies. He posted a 2.19 ERA in seven relief appearances after getting called up the previous September and won a bullpen job out of spring training. McLish taught him to throw a better slider, a pitch that he was beginning to trust.

Jenkins made his first appearance of the 1966 season on April 20 at Connie Mack Stadium in an 8-1 loss to the Atlanta Braves. The Phillies had a 4-3 record but were strapped for pitching. Or so they thought.

The next day, Jenkins was on the field during batting practice when coach Bob Oldis said Mauch wanted to see him. Jenkins thought maybe he was being given a chance to start. But when he walked into Mauch’s office, reserve outfielders John Herrnstein and Adolfo Phillips were in there, too.

“He told us, ‘We just made a trade that’s going to benefit you three fellas,' " Jenkins told the Inquirer’s Frank Dolson in 1971. “At the time, I felt like just walking out. I thought I had the ballclub made. I’d pitched good. Then the season’s seven, eight days old and they trade you.”

The deal was lauded in the press. Jackson, then 34, was two years removed from a 24-win season. Buhl, 37, brought dependability, at least in Mauch’s eyes. A story in the next day’s Inquirer called it a “youth-for-age swap” that signaled the Phillies were making “a frank bid for a pennant this season,” while also noting that “none of the three Phils figured strongly in present plans.”

Jenkins was mentioned only once before the last paragraph, in which his last name was misspelled.

But the Phillies finished fourth in 1966 despite 15 wins and a 2.99 ERA from Jackson. Buhl got released the following year; Jackson pitched only two more seasons. They had gone a combined 47-53 for the Phillies.

Jenkins, meanwhile, was the Cubs’ opening-day starter in 1967 and notched a complete-game victory -- over the Phillies, of course. He made a habit of tormenting his old team. In 43 games (38 starts) against the Phillies, Jenkins went 26-8 with a 2.39 ERA.

"I always tried to beat 'em,” Jenkins said last year. “I always tried to show them that they made a mistake.”

Quinn, Mauch, and then-farm director Paul Owens surely knew it. In 1972, Quinn told The Inquirer that “the Jenkins and the [Alvin] Dark-[Eddie] Stanky deals I’d have to say were the worst” that he ever made. Years later, when Jenkins got into the Hall of Fame, Mauch admitted that he didn’t expect him to develop such pinpoint control.

"I heard some stories [Mauch] didn't think I had a major-league fastball," Jenkins said in 1991. "I don't know what he based that on. He didn't see me pitch that much."

Jenkins’ peak years were six consecutive 20-win seasons from 1967 to 1972. The Phillies were a last-place team for most of that time, as they moved from Connie Mack Stadium into Veterans Stadium and began to develop Larry Bowa, Greg Luzinski, Mike Schmidt and the rest of their homegrown late-’70s core. Jenkins probably wouldn’t have turned the early-’70s Phillies into contenders.

But Jenkins recorded a 3.54 ERA and averaged 16 wins per season for mostly lousy teams from 1973 through 1980. In 1978, at age 35, he went 18-8 with a 3.04 ERA and was worth 5.5 wins above replacement for the Texas Rangers, numbers that would have made him the second-best pitcher after Carlton (16-13, 2.84) on a 90-win Phillies team that lost in the NL Championship Series for the third year in a row.

“You could make a real case that by coming so close in ’64, we hurt our club for the next decade,” Owens said in 1989. “We traded away Ferguson Jenkins, and he turned out to be a great pitcher who could have helped us for years and years to come.”