At the cutting edge of medicine, survival

He still gets shivers being able to turn tragedy into new life.

Howard Nathan set out to be a doctor.

Rejected from medical school, he hoped that networking with some prominent local transplant surgeons might give him another shot at admission.

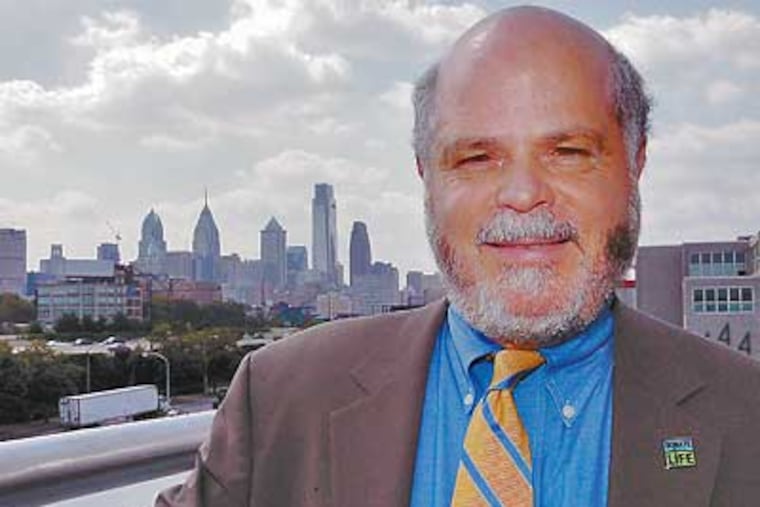

Instead, Nathan, who runs Philadelphia's Gift of Life Donor Program, wound up a world traveler and a prominent leader in the world of organ transplantation. Now in his 31st year at the organ program, he is president of the International Society of Organ Donation and Procurement.

In 1978, Nathan became the third employee of what was then the Delaware Valley Transplant Program. He now oversees 100 employees who cover a region in eastern Pennsylvania, South Jersey and Delaware that he says produces the largest number of organ donors in the world - about 450.

In 2005, he moved Gift of Life into a spotless, 76,000-square-foot building in Philadelphia that has three operating rooms. The organization trains transplant workers from around the world. His newest project is raising funds for a $7.5 million house for the families of out-of-town transplant patients.

Nathan's father, who died when Nathan was 9, ran a dry-cleaning business. His mother worked for minimum wage in a clothing store. Thirteen years after Nathan started working in transplant, his sister got a liver transplant. She died in 2003.

He married for the first time at 50, having devoted, he now says, almost all of his early life to work. He met his wife after a friend surreptitiously placed a singles ad about him in WHYY's magazine. As a concession to her, he now tries to keep his workdays to 11 hours or so.

Question: You started out pre-med. What happened to that?

Answer: I didn't get accepted to medical school. Came to Philadelphia. Worked at Wistar Institute in research. Went back to grad school. Thought that I would do that, and then go to med school. . . . And then answered an ad in the paper for this job called transplant coordinator, and offered to work for free . . . because they didn't want to hire me. They thought I was too young and immature.

Q: So you worked for free?

A: No, I offered. And the guy who was my boss was like, "This guy had the right attitude."

Q: Why were you interested in this job?

A: Two reasons. One is I had heard about the concept of a person being a kidney coordinator from a friend of mine who had heard about a job in Washington. The second thing is all the surgeons were on the boards of the medical schools. So I thought, "Well, I interview here, I work here for a year or two, go to medical school." Never applied again. . . .

Q: Why not?

A: Because [the job] combined the things that I love, which is being on the cutting edge of medicine, working with people who are committed and are passionate about what they do. And I got to use my, I guess you'd say, my personality and social skills in working with families and working with health-care workers. . . . The neat thing about this job, still today, is that, within hours, you turn tragedy into someone's new life. And what other job has that? And so that's a pretty powerful thing that attracted me and still keeps me pumped up.

Q: It is noticeable that you're still pumped up.

A: I'm getting shivers just talking about it. . . .

Q: Why do you think this area has so many organ donors?

A: I think the . . . relationships that we've developed with the hospitals and the health-care workers is key. Them allowing us . . .to work collaboratively with them in approaching families is really a crucial thing. . . . Second is that we were one of the first to do a comprehensive law that mandates the call to us, starting in 1994. We were also one of the first to put [organ donor] on our driver's license and make it a legal consent for organ donation.

Q: What percentage of people put donor on their driver's license?

A: Currently in Pennsylvania, 43 percent. There's 4.2 million Pennsylvania drivers who have it on their license out of about 8.8 million.

Q: That's pretty high, actually, isn't it?

A: Yeah, that's pretty good. . . . In other parts of the country, like Utah, they have upwards of 70 percent of the public on the driver's license. . . .. So that would be our goal.

Q: What . . . has been your biggest challenge?

A: The biggest challenge is the waiting list. The more successful we are, the more successful we are. When I started, a kidney transplant was, at best, maybe a 50 percent graft survival [survival of the transplanted organ] at one or two years. Now, it's well over 90 percent successful. Heart transplants, well over 90 percent successful. Liver transplants, 90 percent successful. So the outcomes are so good, when a physician in the community sees someone with end-stage organ failure, they refer them to a hospital, because they know they can get a transplant. Or at least get on a waiting list. And so the biggest challenge is more and more people get referred, and the waiting list has tripled in the last 12 years.

Q: What would you say is your biggest failure?

A: Boy, that's a tough one. Hmmm. . . . You mean professionally, right?

Q: Not necessarily.

A: Oh, OK. Well, probably not getting married and having kids earlier. I clearly was married to my profession.

Q: How would you compare your goals running a nonprofit . . . to a for-profit?

A: When I took over, I said, "You know what? We need to start looking at goals and objectives and doing strategic planning and making sure that the organization runs so that we maximize the number of people who will benefit." Not like, "Oh, we did good last year, we'll do good next year," that kind of thing.

I started looking at it differently, and started managing it differently, so that I ran it with a compassion for people, but had to make sure that everybody had the same mission and idea that I had. . . .

The way I always talk about it is, "Be the voice of the recipient's family." . . . What we teach here today is dual advocacy. What if it was your family member waiting? What would you want your family member to say to that donor family so they'll donate? Our job is to get people to donate. It doesn't mean that we strong-arm them. It doesn't mean that we coerce them. It means that we do everything possible to make sure they know that this is going to save lives. And if you talk to most people, if they have an opportunity to save somebody else's life, . . . they're going to do it. Kid in a fire, somebody drowning, the first inclination: Save their life. This is no different.

And so the change that I think that I made was getting people to understand . . . the reason that we exist is because there's a waiting list of 6,000 people, of which 400 or 500 are going to die waiting. If we don't speak up on behalf of those potential recipients, those candidates waiting, someone's going to die. And you're not doing your job.

Q: Do you see yourself doing this for the rest of your working career?

A: Without question.

Howard Nathan

Age: 54.

Hometown: Born in Johnstown, Pa. Currently lives in Devon.

Personal: Wife, Elizabeth, 48, an art therapist.

Hobbies: Golf, attending the Transplant Games every two years since 1990. "It just pumps

me up."EndText