PhillyDeals: PhillyDeals: Data the new marionette strings

"We are being quantified," writes Stephen Baker in his book The Numerati, which shows how bosses, retailers, politicians, drugmakers and security agents use Google Analytics and other data-tracking services to learn where we spend, and who and what we watch and visit, through mobile phone, e-mail, Web and video.

"We are being quantified," writes

Stephen Baker

in his book

The Numerati

, which shows how bosses, retailers, politicians, drugmakers and security agents use

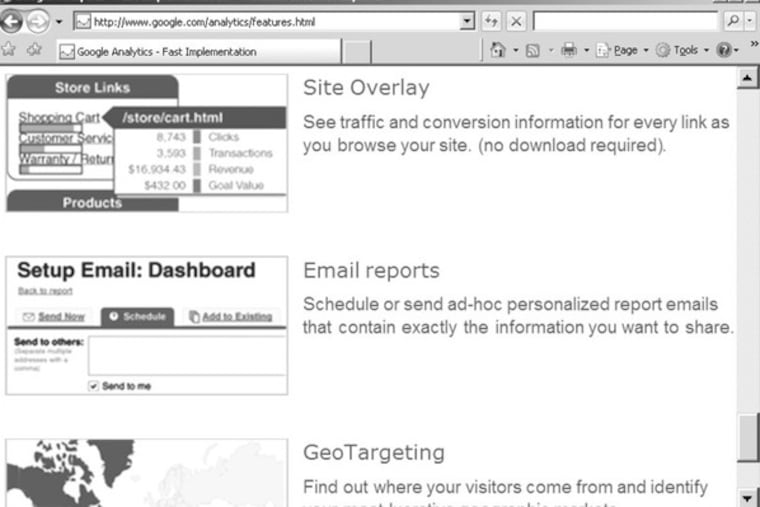

Google Analytics

and other data-tracking services to learn where we spend, and who and what we watch and visit, through mobile phone, e-mail, Web and video.

Can there be too much data? The big Wilmington credit card banks have tracked every dollar we spend on Visa and MasterCard since the early 1990s, but they still haven't been able to figure out how to use it to boost profit above what they made 10 years ago.

Worse, despite all they know about consumer spending, the banks' Wall Street affiliates lost

billions in the last three years by financing stupid home loans to people who didn't pay them back.

But that's pre-Internet technology, Baker says. "Companies are going way deeper" in linking data into digital patterns and creating useful customer and subject profiles, he told me on a visit to Center City yesterday, before an evening talk at the Free Library.

Baker, a BusinessWeek writer who played on the Harriton High School (Rosemont) tennis team with Lawrence Summers (who would go on to become president of Harvard and was named to Obama's economic team), says the biggest U.S. companies are hiring "crack mathematicians, computer scientists and engineers," along with average folks who understand basic statistics, to "turn the bits of our lives into symbols" that companies and governments can use to sell to us, manage us, stop us before we do things they don't want.

That's bad, if you don't like strangers knowing what you buy, eat or download. Baker says tech-company managers get defensive when he summarizes how much they can legally spy. His advice for high school and college kids: Learn more math.

A cautionary tale

Investment banker

Andrew T. Greenberg

, managing director at

Fairmount Partners

, is also co-owner of

GF Data Resources L.L.C

., Conshohocken, which tracks private-company investments and publishes data online. He's one of Baker's digerati.

Greenberg told me Baker "brings into focus a lot of the uses that this information explosion makes possible." At GF, he said, "we release a report, and Google Analytics enables us to track the spike in hits on our Web site, the sites people came from, the pages they hit in our reports, and how long they sit on these pages." He knows who his readers are, what they want, and how to reach them. No charge.

But Greenberg also reads Numerati as "a cautionary tale."

"Until the past year," he said, "we lived in a world where the efficiency of capital made possible by the flow of information looked like an unmixed good thing."

Now, with the economy in crisis, he says: "We see that unlimited and instantaneous access to information doesn't necessarily guarantee a stable economy."

Like atomic science in the 20th century, the explosion of online data looked to its early promoters like a saving force that promised better living at low cost.

But as layoffs spread to tech companies and as business models get wrecked without obvious replacements, all that digital information is turning out to be another vast, bewildering, often threatening field for human endeavor. Even sophisticated data, says Greenberg, "is not enough."

GMAC: Watching, hoping

While

GMAC Financial Services

struggles to raise $30 billion from its bondholders so it can qualify for a taxpayer-funded bank bailout, investors holding $25 billion in uninsured

GMAC SmartNotes

can only watch and hope they don't lose their investments. GMAC employs about 1,900 at its Horsham-area offices.

Two much smaller Philadelphia-area companies, American Business Financial Services Inc. and Walnut Equipment Leasing Co., used to issue similar notes. Both firms financed loans by selling what amounted to uninsured certificates of deposit at attractive interest rates. Both were unable to keep paying when markets turned against them, leaving buyers with dimes on the dollar.