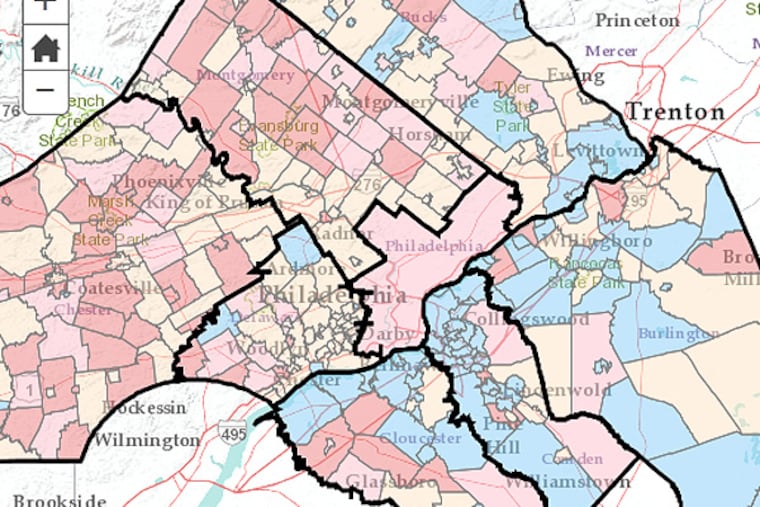

Gains and losses in Phila. region's population

A number of communities in the region's Pennsylvania suburbs, notably in Chester and Montgomery Counties, grew substantially between April 2010 and July 2013, Census Bureau population estimates released Thursday show.

A number of communities in the region's Pennsylvania suburbs, notably in Chester and Montgomery Counties, grew substantially between April 2010 and July 2013, Census Bureau population estimates released Thursday show.

In Chester County, there were noteworthy upticks in municipalities such as Malvern, West Chester, East Brandywine, and West Goshen, and the same was true in Chester/Delaware County border towns such as Bethel and Chadds Ford. In central Montgomery County, Upper Hanover, Towamencin, and Salford were among the burgeoning towns.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia remained the fifth-largest U.S. city, with a population estimated at 1.553 million through July 2013, an increase of just over 27,000 from April 2010. It was the seventh year in a row of population growth, the census data showed.

(Population estimates for neighborhoods within the city limits will not be available until December.)

In New Jersey, some towns continued to slowly lose population, though there were notable exceptions on that side of the Delaware River, as well, the estimates indicated.

Seven of the eight counties in the region grew in population. Only Camden County shrank over the three-year period, down 0.2 percent, according to the Census Bureau, which on Thursday released 2013 population estimates for the region's 340 municipalities in Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey.

Much of that loss was in the city of Camden (0.6 percent), Gloucester Township (0.5 percent), and Winslow (0.8 percent), the numbers showed.

The Census Bureau offered little analysis of the data it released. But, in general, observers of the region's demographic and housing trends said, the data seem consistent.

"The pattern here is one of continued momentum. Townships with good fundamentals remain good places to live," said Kevin C. Gillen, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania's Fels Institute of Government who tracks housing in the region. "But the spike in energy costs is a short-run factor in play behind the numbers. Since the recession, towns that have done well are accessible to public transit and to highways."

Conversely, Gillen said, some locales that have not "are far-flung townships, with no public transport and not near major highways."

New construction lures new residents, and construction in towns like Montgomery Township accounted for three-quarters of the growth, the Census Bureau said in a news release accompanying the data.

Suburban populations will likely keep growing as people young and old seek out new homes and apartments, said economist Joel L. Naroff, of Naroff Economic Advisors in Holland, Bucks County.

"Some second-ring suburbs, like central Bucks County, are catering to baby boomers moving into higher-density housing," Naroff said. "Remember, a few hundred people can be accounted for by just one big housing development."

Closer to the Mason-Dixon Line, he said, the outer ring of Philadelphia suburbs represents "the next logical place to live with buildable land." In addition, Naroff noted, more commuters are living in Delaware and Chester County towns like Avondale and working in Maryland and Delaware, where wages may be higher.

In the inner-ring suburbs, population remained relatively flat between 2010 and 2013, the census data showed, and towns farther out, such as East Brandywine, London Grove, and Montgomery Township led in new residents. But this period of outward population movement doesn't seem as significant as the one that occurred during the prerecession housing bubble.

"Around the country, there are a number of major cities that have been growing faster than their suburbs in recent years, and for the most part that is true in . . . Philadelphia," said Larry Eichel, project director of the Philadelphia Research Initiative at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

"This phenomenon appears to be fueled by three factors: foreign immigration; the preference of the millennial generation for urban life, and baby boomers leaving the suburbs after their children are out of the house," Eichel said.

Some observers cautioned against jumping to conclusions about individual municipalities. For example, a prison (Graterford) in Skippack, Montgomery County, could account for a population increase there, said Susan Copella, director of the Pennsylvania State Data Center at Penn State Harrisburg in Middletown.

"Cities have been witnessing growth for the past few years. Younger people moving in, and not just in Philly," Copella said. But across Pennsylvania, "the majority of the growth we saw is in townships - they grew 78 percent over the three-year period."

That's chiefly due to the fact that smaller boroughs are more often fully built out, she said.

Some Bucks County locales, such as Falls Township, continued to lose residents. River towns nearby such as Bristol have been declining since the steel industry closed down in the 1980s.

In New Jersey, a ribbon of towns along the Delaware in Gloucester, Camden, and Burlington Counties lost residents, the census numbers showed. But some towns, such as Cinnaminson and Woolwich, defied the trend, gaining 7.7 percent and 10.4 percent in the three-year period.

Cinnaminson boasts new housing developments and access to the Camden-Trenton River Line, Gillen said. "That goes to the transit story and the cost of energy."

With $4-a-gallon gasoline, he said, "heating and cooling a 6,000 [square] foot home plus driving a 110-minute commute is very expensive these days."

In southern Gloucester County's boomtowns, growth and building permits go hand-in-hand.

"There have been substantial permits issued in East Greenwich and Woolwich. It's been growing for more than three years," said Sen-Yuan Wu, a research economist at the New Jersey Department of Labor & Workforce Development in Trenton.

Older housing stock is behind population loss in many South Jersey towns, said Noemi Mendez Eliasen, information-services specialist with the Census Bureau's Philadelphia regional office.

"Magnolia and Runnemede . . . have old houses, and that influences whether people want to live there or escape an older home," she said.

215-854-2808