Biotech jobs up, pharma down nationally

When health-care giant Johnson & Johnson told Renold Capocasale in October 2009 that he was losing his job, he got very quiet, which was not the norm for a friendly, chatty guy.

When health-care giant Johnson & Johnson told Renold Capocasale in October 2009 that he was losing his job, he got very quiet, which was not the norm for a friendly, chatty guy.

"That was absolutely the lowest day of my life," Capocasale said recently. "I really questioned my self-worth. I had published many things and been promoted lots of times, but I thought, 'Why me?' "

Scroll forward to the present, and Capocasale has more than recovered. In March, he celebrated the fifth anniversary of incorporating his small biotech company, FlowMetric. He will join about 15,000 people when BIO, the national biotech trade association, holds its annual convention at the Pennsylvania Convention Center on Monday through Thursday.

In many ways, the biologist's experience reflects the drug world's evolution.

Tens of thousands of jobs worldwide in some of the biggest pharmaceutical companies have disappeared or been outsourced to other companies, an Inquirer analysis shows. Those fortunate enough to have kept jobs had healthy raises, on average, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data.

Some people also shifted to smaller biotech companies that might be years away from selling any medicine but are growing, in part because Wall Street is gambling that future profits will be born there. Biotech companies develop products from living cells - biology - whereas many pharmaceutical products are chemical-based.

Federal Reserve chairs rarely speak of individual industries, but biotech stocks have surged enough in recent years for Janet Yellen to fret about a bubble.

"Over the last 10 years, the pharma industry has been contracting and consolidating with mergers and acquisitions, but also outsourcing many of the functions that were historically held in-house, functions that every pharma company has and considers almost a commodity," said Chris Molineaux, head of Pennsylvania BIO and convention host. "Another big factor is that their pipelines, their R&D machines, have not been producing as much or as efficiently as they once did, and they are looking outside to start-ups."

One exhibitor at the convention will be Kelly Services, the temporary employment company that has seen 20 percent to 25 percent growth in life sciences work since the recession.

Overall, life sciences employment in Pennsylvania has risen from 79,000 to 85,000 jobs since 2005, when the BIO convention was last in Philadelphia, according to Fourth Economy Consulting, through November 2013. "It is a whole patchwork of much smaller companies," Molineaux said.

The Inquirer review of BLS data showed national employment in the "pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing" category fell from 291,795 in 2003 to 277,113 in 2013, the latest year available.

Jobs in the "research and development in biotechnology" category rose from 135,424 to 142,475 between 2007 and 2013.

Using those categories and periods, Pennsylvania lost pharmaceutical and biotech jobs. New Jersey lost pharma jobs but gained in biotech. California gained in both categories and had the most pharma employees (45,185). Massachusetts also gained in both categories and had the most biotech jobs (28,060).

"Massachusetts and California grow faster than Philly for two reasons: They have a critical mass of talent and companies that acts as a magnet, attracting more talent and companies," said Erik Gordon, a University of Michigan business school professor who follows the pharmaceutical industry. "Philly has activity but lacks the mass to attract more. It is at risk of losing activity to the more active and attractive regions. Massachusetts and California also have a huge amount of world-class academic research activity that seeds the new approaches to therapeutics. Philadelphia has high-quality research in much smaller amounts."

BLS statistics show that in the "pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing" category, more than half of the Pennsylvania jobs were in Montgomery County, where employment fell from 13,818 employees in 2003 to 9,792 in 2013. In that period, the average annual salary rose from $90,753 to $136,286. Montgomery County had similar employment declines and salary increases in the biotechnology category.

Capocasale, the former J&J employee, grew up in Fort Washington, Montgomery County. Many people and families have never recovered financially from being laid off, but he used the available help and is much happier now.

Capocasale said his wife, Nancy, thought he was nuts to convert his 401(k) into seed money to try to start a business with experience only as a biologist. But her emotional support and income as a vice president in finance at Comcast gave him time to get funding from friends and family to start his own company: FlowMetric.

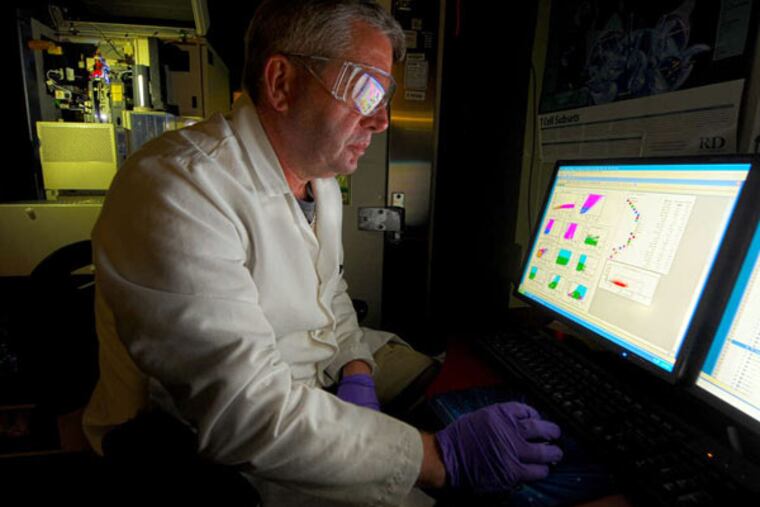

Flow cytometry is the process of tagging and identifying different types of cells as part of making drugs. Now with 12 employees, most based in Bucks County, FlowMetric provides the same services to many clients - including J&J - that Capocasale did as a full-time J&J employee.

The company became profitable in 2014 and is expanding to Europe.

At the BIO convention, Capocasale will help unveil a patented mobile flow cytometry unit. He imagines its being used in American shopping malls or remote locations in developing countries to detect allergies and determine the efficacy of vaccines with the prick of a finger and a drop of blood.

Now, at 52, and earning more than he did when he was laid off at J&J, Capocasale is excited about his future and can laugh about the worst moments.

His two sons, for example, were young enough at the time not to understand the impact of his job loss or grasp the terminology.

"My oldest son told his class, 'My dad got laid,' " Capocasale said with chuckle. More seriously, he said, "because of their mom's job, we never suffered the way so many people do."

215-854-4506@phillypharma