From the Archives: The Dorrance legacy of control at Campbell’s

How a patriarch kept a grip on his company.

This article was originally published on Mar. 18, 1991.

Second in a series.

He was a curiosity at the Joseph Campbell Preserve Co. A 24-year-old chemist, two degrees to his name, ample job options. Why would he want to work for a canning factory?

But when John Thompson Dorrance took over a sparsely equipped laboratory at the Camden factory in October 1897, he knew exactly what he wanted. He saw dollar signs in the soup business and set out to make condensed soup an American staple.

When he died three decades later, John Dorrance was sole owner of Campbell Soup Co. and worth $115 million — a fortune that would equal more than $850 million today.

He was obsessed with building the business — and with retaining family control of it. He wrote six versions of his will and added nine codicils, all in an attempt to create an ironclad grip on Campbell Soup for his family.

And he took a series of extraordinary steps to see to it that family control of the business would not be weakened by his heirs having to sell Campbell stock to pay tax collectors.

In one tax-saving move, he withheld control of the company from his own children. All the profits would go to them and their mother, but the actual ownership of his shares would pass to his grandchildren.

Family control was safe.

Or so he thought.

Sixty-one years after the death of John T. Dorrance, his grandchildren are squabbling over the family legacy. Through his foresight, they inherited extraordinary wealth; six have fortunes today in the range of $450 million to $1 billion. But now, three — Dorrance Hamilton, Diana Norris and Hope van Beuren — want to cash in their inheritance.

Even if it means undoing everything their grandfather did to keep Campbell Soup in Dorrance hands.

∎

When John T. Dorrance showed up at the canning factory in 1897, most co- workers assumed that he had been put on the payroll by his uncle, Arthur.

Fifteen years before, the elder Dorrance had become a partner in the canning company started in 1869 by Joseph Campbell, a fruit merchant, and Abram Anderson, an icebox manufacturer. Later, he replaced Campbell as president.

But Arthur Dorrance wasn't anxious to hire his nephew. Too much the scholar, he thought. Not the sort who could be happy making jams and preserves, and packing vegetables and fruits for the rest of his life.

John Dorrance persisted, though. Forget his bachelor's degree in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Never mind his doctorate in organic chemistry from the University of Gottingen in Germany, or the fact that four colleges — Columbia, Cornell, Bryn Mawr and Gottingen — were trying to recruit him for their chemistry departments.

Academia would never be able to hold John Dorrance. He was one of those restless scientists with the skill, savvy and ego to turn an innovation into a fortune. And he had settled on the Campbell company as the place to do it.

The business genius of John T. Dorrance has been compared to that of Henry Ford, but unlike Ford, Dorrance's life has never been fully chronicled. The Inquirer reviewed estate records, court testimony and other documents, and interviewed friends, former Dorrance employees and family members to construct a portrait of an American dynasty.

Dr. Dorrance — the title he later preferred — accepted a token salary of $7.50 a week and his uncle's demand that he outfit his laboratory at his own expense. He was out to prove himself.

While studying abroad, Dorrance had been impressed by the soups he had enjoyed at European dinner tables. Soups were nutritious and a good way to balance a meal, he noted. But back home, where convenience was a big issue, prepared soups were expensive and packaged in big, cumbersome cans.

His idea: Take the water out of the soup, through cooking. That way, he reasoned, you could reduce the size of the can.

It would cost less to package, ship and store the soups. Those savings could be passed on to consumers, who were then paying about 30 cents for a 32- ounce can of soup. Dorrance's target was to sell a 10 1/2-ounce can of "Campbell's Condensed Soup" for a dime.

But the soups didn't cause an immediate revolution. People didn't trust the quality of such a low-priced item and, besides, soups were usually reserved for formal meals.

Dorrance would have to give consumers good reasons to buy something they had never tried. He turned to advertising, spending the then-huge sum of $4,264 to cover trolleys with "car cards" promoting soup.

Advertising became a hallmark of Campbell. In 1904, the company created one of the most enduring advertising images: the cherubic Campbell kids, created by Grace Gebbie Drayton of Philadelphia. (The familiar "M'm! M'm! Good!" wasn't created until the 1930s for two Campbell-sponsored radio shows, Amos 'n Andy and the George Burns and Gracie Allen show. )

At Dorrance's insistence, the company began to phase out its other products in favor of soups. Pork and beans were added, but only to keep the assembly line running on days when beef stock for the soups was being made.

With the increasing success of soup, Dorrance quickly moved up in management and, as he did, he used every penny he had to buy stock from his uncle and other partners.

The word within the company was that they were willing to sell stock to Dorrance because he threatened to start a competing business. He had the recipes and he could easily set up his own kitchen. If he did that, their Campbell stock would be worthless.

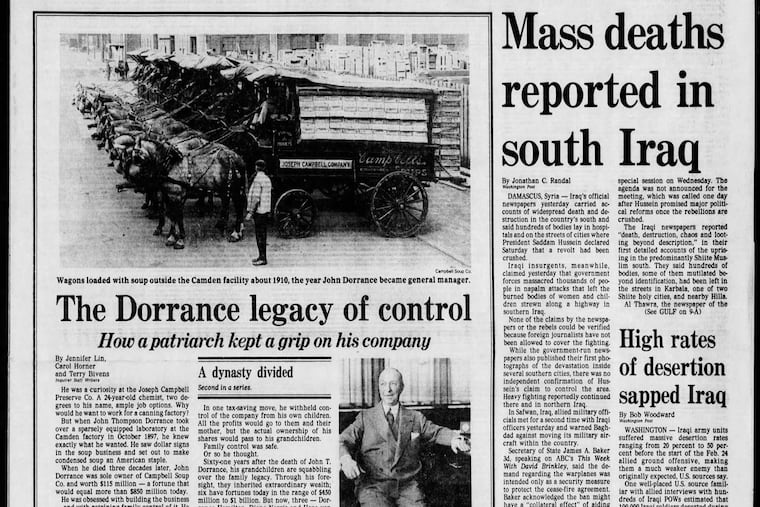

In 1910, he became general manager. Not one to delegate authority, Dorrance delved into every phase of production, from advertising to cultivating varieties of tomatoes. He tended a tomato patch near the front door of his home, a 76-acre farm in Cinnaminson, Burlington County, where he and his wife, Ethel Mallinckrodt Dorrance, had moved with their growing family in 1911.

When Arthur Dorrance retired in 1914, John Dorrance took over as president. A year later, on June 3, he bought the last of his uncle's stock, making himself sole owner.

Within the family, it was believed that in all, John Dorrance paid his uncle $5 million.

At 42, John Thompson Dorrance was well on his way to becoming a legend. Before long, he and his wife would show Philadelphia society just how rich the soup business was.

∎

This was the moment Ethel Dorrance had been waiting for. Her eldest daughter, Elinor, was making her debut at the family's Radnor estate, Woodcrest, and the gatekeepers of Main Line society were about to get their first glimpse of the Dorrances' wealth.

It was a perfect cool autumn day. Elinor, a delicate 18-year-old with bobbed light hair and doe eyes, wore a calf-length silver lace dress and carried a bouquet of cascading orchids. Her mother chose a dramatic black- beaded dress. The next day, one society-page chronicler purred that it was "one of the most beautiful teas of the season. "

The Dorrances were on their way. Within months, they joined the Vanderbilts, Dukes and Biddles in the Social Register.

Only days before Elinor's 1925 tea, Ethel had moved her brood from Pomona Farm in Cinnaminson to Woodcrest, a medieval-style mansion set on a thickly wooded ridge in Radnor. The rambling Main Line estate was 15 miles and a world away from the tomato patches of Pomona Farm.

Ethel had made no secret of her dislike for the farm. She described its three-story, 12-bedroom brick house as "very ugly, but very comfortable inside. "

But John Dorrance liked the place. One minute he could be sitting at his desk in Camden, the next, tending tomatoes with his sleeves rolled up. He didn't yearn for the life of the idle rich. He didn't pass his time giving away money to charities. He didn't sail yachts or hunt foxes or race thoroughbreds. He was too busy making money.

He had other reasons, too, for not wanting to move, his lawyers and associates explained in a 1931 trial over inheritance taxes.

By now a rich, middle-aged man, he began to dwell on his mortality and the future of the business. He wanted his family to retain control of Campbell Soup and, more important, he wanted to pass on as much of his fortune as possible to them. Dorrance knew the tax laws in New Jersey would be more favorable.

Ethel Dorrance, however, won out. If her husband wouldn't move, fine. He could stay in Cinnaminson whenever he wanted. But everyone else would move to the Main Line.

She was eager for a life among the suburban castles and country clubs of the Main Line. She wanted her younger children — Charlotte, who was 14 in 1925; Margaret, 10, and John Jr., 6 — to attend private schools "with children with their prospects in life. " And she wanted her older girls — Elinor, 18, and Ethel, 16 — to make proper entrances into society and, of course, to marry well.

The Dorrances bought Woodcrest in 1925 for about $350,000 and spent $465,000 for renovations and decorating. It took 26 servants to run the estate.

When the family moved to Radnor, John Dorrance's income was about $3 million a year, according to a report in the Philadelphia Record when he died in 1930. Today that would be more than $22 million a year.

So attractive was Campbell Soup Co., the name the company officially adopted in 1922, that Dorrance was offered $120 million for it, according to the same newspaper account. He flatly refused that and all other offers.

Woodcrest became a regular stop on the Main Line social circuit. "One of the great showplaces," said W. Thacher Longstreth, a Philadelphia councilman who was a friend of the Dorrances' only son, Jack.

"The Dorrances always had the best orchestra, the best food, the best liquor," said another family friend. "No one ever refused an invitation, and everyone would stay till 3 or 4 in the morning. "

To outsiders, the Dorrances lived a charmed life. They had it all: money, attention, power. But family life was troubled below the surface. Friends say that John Dorrance drank heavily, a problem that would afflict some of his children, too, and scar relationships in the generation to come.

"Underneath all that glamour was a lot of misery," said a family friend. The Dorrances were new money and not allowed to forget it.

"The very solid matrons looked down on them," the friend said. "The drinking was brought on by a feeling of inferiority that went through all of those kids — a feeling of not really being accepted, a feeling that they were brought into society because they had money and parties. It weighed more on the girls than Jack."

John Dorrance never felt comfortable at Woodcrest. A friend, Theodore Grayson, recounted later Dorrance's reaction to a compliment on his new home. Snapped Dorrance: "I don't like this damned place. I feel as though I were a bug under a glass case in a museum when I am in it! "

Dorrance could be at once extravagant and stingy. He was so annoyed about the high electric bills at Woodcrest that he threatened to take the light bulbs out of the servants' quarters. Butlers had to pay to get their clothes washed at Woodcrest and got two uniform shirts a year — as Christmas gifts.

Yet the family spent money on parties like true hedonists of the Roaring '20s. Dorrance sprang for $100,000 for a coming-out party in 1927 for his daughter Ethel, who was known as Fifi. His money transformed the Bellevue- Stratford Hotel into a tropical fantasy, complete with cages of exotic birds and monkeys. Two bands played until dawn, one featuring an unknown singer named Bing Crosby.

With such large inheritances at stake, Fifi and her sisters were hounded by reporters. A New York gossip columnist told how Margaret and Charlotte once arrived at a Philadelphia shop from a cocktail party "and showed signs of being in an extremely gay mood. " To the amazement of shop clerks, the sisters "put on a terrific striptease — complete with hula-hulas and real burlesque technique. "

A big story was Elinor's decision to work as a Campbell clerk for 31 cents an hour. She was celebrated as the debutante laborer. After three months, Elinor put her "career" on hold, sailed to Europe and returned months later on the arm of her fiance, Nathaniel P. Hill, a New York investment banker.

Before long, the Dorrances were joining other Philadelphians of their class for vacations in Bar Harbor, Maine.

That first summer in Maine, in 1929, Dorrance decided to hire bandleader Howard Lanin — for the entire season. The cost for the nine-piece band: $43,000. "No one knows me up there, so I thought if I brought you along, it would be a way to meet people," he told Lanin.

Some days, the band played for John and Ethel Dorrance as they lunched on sandwiches with their 10-year-old son, Jack.

When a neighbor, a Pulitzer family heiress, asked to hire Lanin's band, he said he had to get permission from Dorrance, who responded, "Go play for her, but charge her! "

All through the vacation, Dorrance took phone calls from his Wall Street investment adviser, Sidney Weinberg of Goldman Sachs & Co. Weinberg's advice: Sell stocks! "John Dorrance was dumping the market" in the months before the great crash of 1929, Lanin said. "He didn't lose a dime. "

But in between the good life and stock-market coups, there was trouble. Destructive bouts of drinking were leaving Dorrance irascible. His health was deteriorating. "He told me, 'Howard, I have $40 million in a bank in Boston and I'd give it to anyone who could make me feel better,' " Lanin said.

The next season in Maine, John Dorrance became seriously ill. The family returned to Philadelphia by train on Sept. 15, 1930. He and his wife headed to Pomona Farm, the children to Woodcrest.

It was a hot, muggy evening. Dorrance took refuge on the porch, where he could look out on the lush, beautiful elms and the blue and violet hydrangea bushes.

The next morning, as he sat in a chair waiting to be shaved, Dorrance suffered an embolism. For four days, he lay in a coma. On Sept. 21, 1930, he died. He was 56.

∎

The father built a monument to himself and his family. And when he died, he directed his only son to protect that legacy, the Campbell Soup Co.

The father was stern and the son was obedient.

Carry on what I started, the father ordered in his will. Work for the company. Don't sell the business. Don't lose control.

Yes, sir.

Young Jack was a lanky child of 11 when his father died. The man he never really knew became for the boy "the hero of my life. "

Jack went to the private Montgomery School in Wynnewood. He earned good grades, had many friends and played promising games of tennis and basketball. But overnight, he was crowned with a title that made him at once a prince and a prisoner.

"He was marked wherever he went as the heir, the only boy, of the terribly rich Dorrance family," said a friend.

In a 28-page will, Dorrance left his son an allowance of $20,000 a month — an embarrassingly large sum during the Great Depression, when millions were without work. Jack's sisters each received $10,000 a month.

Beyond the allowance, income from the Dorrance estate was also weighted in Jack's favor: He would get one-fourth of the income, as would his mother, but his four sisters each would get one-eighth.

More important, the will stipulated that when each of the Dorrance children died, their children would inherit the company's stock. But Jack's heirs, as a group, would get double the amount of stock allotted to the children of each of his sisters.

Dorrance wanted to see his son follow him into the business and stated so in his will:

"It is my desire that my son be given the opportunity to learn the business of the Campbell Soup Co … and to demonstrate his ability to hold a position of trust. "

Yes, sir.

A sale should be considered "only after the greatest deliberation. "

Yes, sir.

And if the company must be sold, be sure the family retains at least 52 percent of the combined company's stock.

Yes, sir.

Those were the tenets that Jack Dorrance lived by.

"I always knew I'd work for the company. It was never discussed. It was just accepted," he told Fortune magazine in a 1987 interview.

Growing up, some boys might have recoiled from such responsibility, might have rebelled. But Jack Dorrance accepted and then became consumed by it. "The company was everything for Jack," said Robert D. Dripps 3d, son of his third wife, Diana. Said a confidante: "It was his religion. "

The estate left by John T. Dorrance was the third largest in the country. The inventor left all of the Campbell stock — worth $79 million at the time — to his family, through a trust. None went to charity.

"He would want those who profited from his labor to be completely his own flesh and blood," said David R. Dorrance, a nephew of the inventor. "He wanted mirrors that would throw back his own image … He certainly wanted his lifework to remain intact. "

The inventor insisted that the mausoleum at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd be reserved for people with the surname Dorrance, David Dorrance said. In 1937, when the firstborn child of the patriarch's daughter Ethel Colket died of leukemia at age 3, Dorrance's widow had a twin mausoleum built so the girl could be buried there.

John Dorrance's married daughters sometimes joked about being excluded from the mausoleum reserved for their parents and brother. "All right, we can't be in mausoleum number one, but we'll have a fourth for bridge in mausoleum number two. And we'll have Peter (a butler) to serve the martinis! " Charlotte Dorrance Wright said to her sister Ethel, according to the nephew.

For Jack Dorrance — trumpeted in the Philadelphia Record as "the nearest thing to a reigning earl or duke that we have in this nation" — wealth sometimes was a burden.

Howard Butcher 3d, chairman emeritus of Butcher & Singer and one of Jack's regular poker and golf partners, said: "He felt very conscious of the fact that his father had made the money and he hadn't. I don't think he found any great joy in being rich. I think he found it as embarrassing as it was fun. "

At Princeton University, Jack didn't flaunt his wealth or play the coddled rich boy, said Walter D. Pinkard, a roommate. One of the few signs of his wealth was the valet from Woodcrest who appeared each Saturday to whisk away his dirty laundry and return it, pressed and cleaned, the next day.

But it was an effort for Jack to be just one of the guys. Often, reality intruded in harsh ways. In 1940, the same year he was named "Bachelor of the Year" by Philadelphia debutantes, news reports about a family tax battle dredged up the fact that he was getting an allowance of $20,000 a month.

"It was the talk of the university," Pinkard recalled. "You couldn't possibly spend that much money in those days. "

His popularity on the rise, Jack was swamped with new "friends," who would lasso him on Friday to drive up to Manhattan for a night of dancing to Benny Goodman's band at the Rainbow Room. When the revelry ended, they stuck Jack with the bill.

"Jack's smart enough to know you don't acquire that many friends overnight," said a classmate. "He drew back. It made him more reclusive. I could see him changing, I could see him getting suspicious of people. "

The tax fight during Jack's senior year at Princeton was merely one in a series of courtroom showdowns that ensued after John Dorrance died in 1930. The crux of the disputes was the question of how much the estate owed and to which jurisdictions.

The most crucial issue was, where did Dorrance live?

In the first estate trial in 1931, the executors protested paying inheritance taxes in Pennsylvania, claiming that Dorrance had lived in Cinnaminson.

It was an important distinction. Not only was the tax rate lower in New Jersey, but the tax code there would have better protected his estate from disgruntled heirs.

Under Pennsylvania law, his widow would be entitled to one-third of his personal property — more than he was willing to leave her. New Jersey had no such provision.

Dorrance didn't want his estate to have to sell stock to pay off his widow. To forestall a challenge, he had her sign a statement saying their legal residence was New Jersey.

Dorrance further made a point of telling all who would listen that his home was Pomona Farm, not Woodcrest.

But the charade didn't work.

After his death, New Jersey assessed the estate $16,768,478. Pennsylvania followed with its own tax bill of $31,465,200.

The family fought back, taking Pennsylvania to court in a high-profile case that diverted a Depression-weary public. The 1931 trial in Delaware County provided a rare glimpse into the champagne life at Woodcrest.

A grieving Ethel Dorrance, clad in black, had to explain how one of the butlers rang up grocery bills of more than $400 a month. The family had to turn over every bill for jewelry from Bailey Banks & Biddle, every receipt

from the beauty salon of Strawbridge & Clothier for manicures and hair waves.

But these were expenses the Dorrances could well afford: John Dorrance's salary alone that year was $216,666.

When he died, Dorrance bequeathed his entire fortune to his family — his Campbell stock, $32 million in other stocks and bonds, $4.2 million in cash and insurance. His widow and children received everything, right down to the gasoline in the family cars.

On the question of residence, Judge John B. Hannum ruled in favor of the family — that they lived in New Jersey. But his decision was overturned by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania after the state appealed.

When the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case, the estate had no choice but to pay an agreed-upon tax bill of $17,437,665 — money earmarked to help keep 13,000 Pennsylvania families on relief.

And what of New Jersey's tax claim?

The answer is what makes the Dorrance family's tax problems a landmark case for estate lawyers even today.

Tax collectors in New Jersey sat quietly as the estate battled it out in Pennsylvania. When the dust settled, they paid a call on the executors, who had just finished arguing vociferously that Dorrance was a New Jersey resident. They presented their own tax bill.

The ensuing protest by the estate again worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which once again declined to hear the family's appeal. The estate had to pay New Jersey $16,811,103.50.

What had begun as a two-pronged scheme to save millions of dollars in taxes, while retaining the family's lock on its Campbell stock, ended with the estate being hit with a double-whammy bill of $34,248,768.50.

But that loss was soon offset by rising soup profits. By 1938 the estate had grown in value to $127 million — testament to the strength of the company that young Jack Dorrance would soon take over.

∎

Before reporting for duty at Campbell Soup, Jack was detoured by World War II.

He was inducted into the Army in July 1941 as a $21-a-month private. After training, he became an officer and was assigned to the Signal Corps at Camp Crowder in Neosho, Mo. Later, he worked for the elite Office of Strategic Services — a forerunner to the CIA — and was stationed in southern China.

While in Missouri, in the summer of 1942, Lt. Dorrance went to a servicemen's party in Joplin, where he met a local debutante, Mary Alice Bennett. It was, as her relatives would recount, "love at first sight. "

Six months later, the shy, 23-year-old millionaire proposed. News of the betrothal didn't hit the society pages in Philadelphia until 10 days later, after Mrs. Dorrance and Jack's sister Ethel had a chance to dash out to inspect the bride-to-be.

"She is a very charming, beautiful girl," Mrs. Dorrance said upon her return. But Jack's impetuous romance disappointed his mother and four sisters, who doted on him and had wanted to help pick a suitable mate.

It wasn't that Mary Alice — or Malice, as her friends called her — didn't have a pedigree. Her father, Harry, was a well-to-do executive with a real estate and mining company. And she was an alumna of Sweet Briar College, an exclusive Virginia school.

It was just that being the toast of Joplin, the "Gateway of the Ozarks," wasn't the same as being a Main Line aristocrat. Gossips referred to Mary Alice as "that girl from the hills," one of Jack's friends recalled.

The wedding was intimate. Only 30 people attended the Episcopal service on May 27, 1943, in Joplin. Mrs. Dorrance wore black.

Jack and his wife returned to the Main Line in 1946, after he was discharged as an Army captain. They took up temporary residence at Woodcrest with their two young sons, John T. 3d and Bennett.

Unlike his father, when Jack showed up for work that year, he didn't know what he wanted to do. He was sent to personnel, which assigned him to a job on the factory floor, reviewing the wages of hourly jobs.

Next came a succession of postings as an "assistant" to four executives, which amounted to a 14-year apprenticeship in the ways of Campbell Soup. The jobs gave him a firsthand look at the inner workings of the business without taking on management responsibility, just as his father wanted it.

John T. Dorrance had seen the empires of too many entrepreneurs crumble in the hands of their heirs. And though he wanted his son to one day sit atop the management pyramid as chairman, Dorrance thought the day-to-day job of steering the business should be left to professionals.

Jack grew to view his role at Campbell Soup less as the captain of the business and more as the custodian of the family fortune. He had ultimate veto power, of course. But he involved himself mostly with details, such as making sure a piece of pork was always placed at the top of a can of pork and beans.

"The family had nothing to do with the operation of the business. Nothing," said William Beverly Murphy, a former Campbell CEO and Jack's mentor. "That's the way John T. Dorrance Sr. wanted it, and that's the way it was. "

At work, Jack carried out his father's wishes. He arrived at 8 a.m., taste- tested soup and kept a watchful eye on the company's image. A friend recalled how, on a hunting trip in Hebbronville, Texas, (pop. 4,000), Jack stopped at a local market, rearranged the soup cans and bought the damaged ones — never revealing who he was.

At home, he enjoyed a lifestyle that would make his ambitious mother proud. Renoirs and Monets hung on the walls of his mansion on Monk Road in Gladwyne, and orchids bloomed in the greenhouses. His free time was spent sailing his 68-foot yacht, the Duna, in Newport or pheasant-shooting at his Crow's Nest farm in Chester County.

"The war was behind him," his niece Dodo Hamilton told an associate. "He had a lovely wife and two boys. He had done all the right things. "

All seemed perfect.

It wasn't.

Looking back, many friends contend that Jack was overwhelmed by other people's expectations.

"He never really enjoyed what he had," said a Gladwyne friend. "Jack almost wished he didn't have all that money because it was such a responsibility. "

His life, friends said, was filled with contradictions.

He dined with presidents and princes, and swapped soup casserole recipes with his hired help.

He frequented the symphony and art exhibits, but preferred stealing away to a bird sanctuary to practice wild turkey calls.

He hobnobbed with the rich but was more relaxed talking crops over coffee with the farmer who ran Crow's Nest.

Jack, some friends say, was a reluctant tycoon. Although he was one of Philadelphia's most visible philanthropists, he took equal pleasure in giving anonymously. But the more people sought him out for his money, the more he retreated.

"Obviously, everyone was after him, trying to get money, and it made him standoffish," said Howard Butcher.

In many ways, Jack Dorrance was like his father — trapped like "a bug under a glass case. " But there was a difference.

"I think it was hard for him because he didn't have his father's ability," said Jack's cousin, David Dorrance, who now lives in France. "There was always this struggle to live up to this highly motivated and highly successful father.

"The terror of him must have been that he somehow would spoil his heritage or somehow dissipate it. "

Jack was the man with everything. But even as money empowered him, alcohol was weakening him and putting a strain on his marriage, many of his friends and associates say.

As one friend explained, Jack and Mary Alice "were completely mismatched. And to cover up the whole situation, he drank. "

"When Mary Alice came here, she came as a stranger," recalled the friend. "She had difficulty fitting in with the group that Jack had contact with, and therefore she was very sensitive to any criticism that he had of her. "

But Mary Alice tried to mix, with some success. One of the couple's favorite pastimes was Sunday afternoon cooking parties after a round of golf. In their basement family room, which had a kitchen, Jack would hand out new recipes for his friends to try, often ones that used Campbell products.

They played bridge — poker if it was just the men — and watched Milton Berle on television, enjoying "bull shots" made with beef broth and vodka. With mock solemnity, the group dubbed itself the Benevolent Marching and Philosophical Society: marching for the golf, philosophical for the poker.

Friends remember Jack Dorrance's unexpected and sometimes ribald sense of humor. He delighted in taking visitors on a tour of the artwork in his garden, only to surprise them with a whimsical statue of a man in a business suit — urinating.

The early years were a period of young married tranquillity. But the more outgoing Mary Alice became, the more uncomfortable Jack seemed to get and the more he retreated, acquaintances say.

One escape was to go hunting, as far away from Gladwyne as he could get. He was a skilled marksman and fisherman; he shot quail in England, fished salmon in Quebec and hunted other birds on plantations in South Carolina and Florida.

"On these trips, he almost never talked about the company," said a friend. "It was freedom to him. He was under no pressure. "

At home, Jack's relationship with his children was strained. "Ippy," as his eldest son was called, was a difficult child who was always "testing his father," said a family friend. The friend recalled that Ippy once started a fire in the family's formal living room — on the floor, not in the fireplace.

Bennett, two years Ippy's junior, was less impudent but no closer to his father. Of all the children, Mary Alice, the youngest, was considered Jack's favorite. Horseback riding was her passion, and often Jack would rise before dawn to drive her to competitions.

Jack had a hard time putting down his guard, even with his children, a friend said.

Dodo Hamilton observed to an intimate that a rambunctious child like Ippy, who might have longed for a warm hug, was more likely to get a directive — "Now we're going to go shooting, now we're going to do this.

"Jack didn't have a father, so he didn't know anything about fathering. " He had lost his own father when he was 11.

His struggles with drinking wore on the family. "Jack tended toward alcoholism at some periods of his life," said his cousin, David Dorrance.

"When he was under stress, that's when he would drink," said Belton K. Johnson, a former Campbell board member and Texas hunting pal of Dorrance's.

On July 11, 1963, Mary Alice filed for divorce. She relocated to a town near Geneva, where the family owned property.

Friends say the divorce was hard on the children, who moved with their mother to Switzerland. Ippy was 19, Bennett, 17, and Mary Alice, 13. Mary Alice returned to Philadelphia to finish high school, but the boys were estranged from their father for years.

The divorce was an emotional nadir for Jack Dorrance.

After his wife left, a former employee from his childhood home of Woodcrest recalled getting an urgent call from Jack, asking him to come quickly.

When the employee, who hadn't seen Jack in years, arrived in Gladwyne, he found Jack Dorrance sitting alone in a darkened room. He had been drinking and was melancholy.

What was the matter? the man asked.

There was a problem with his daughter. "Mary Alice said she won't visit me unless I bought her a horse. What should I do? Should I buy her a horse? "

The former employee tried to cheer Jack, assuring him that everything would work out and maybe the children would return.

"No," the millionaire mumbled, his voice trailing off forlornly. "I don't think so. "