PhillyDeals: There's money in eavesdropping on Twitter

We still don't know how Facebook, Twitter, and the other "social media" are ever going to make money or pay back the hundreds of millions of dollars that apparently sober investors have thrown at them at a time when the real economy was grinding to a halt.

We still don't know how Facebook, Twitter, and the other "social media" are ever going to make money or pay back the hundreds of millions of dollars that apparently sober investors have thrown at them at a time when the real economy was grinding to a halt.

But suburban Philadelphia native Evan Britton has an idea.

"Five hundred start-ups have tried to get people away from Google, and they've mostly failed. But the real-time Web is different," insists Britton, founder of Sency, an embryo firm he says is about to move with him from Los Angeles to Rittenhouse Square.

Search engines like Google typically work by counting how many Internet users have hit particular sites in the past, and directing traffic to them.

By contrast, "real-time" applications like Sency aggregate chatter from "social media" like Facebook or Twitter to tell where users are and what they're saying at the moment.

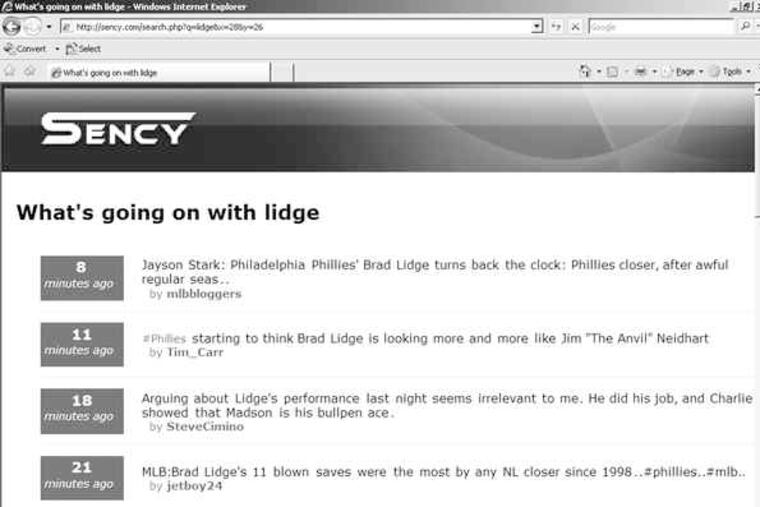

Go to Sency.com, hit "Feed for Websites," go to the "Keyword" box, and enter "Lidge" or "Villanova" or anything else. You'll see who is Twittering about that subject and what they're saying. Advertisers want to know this, and the demand for this kind of eavesdropping will explode as social media circles the globe, Britton says.

"We offer a free, private-labeled feed for Web sites and blogs [to] publish real-time content on their sites," says Britton. It's a "widget," an easy-to-use Internet application, designed to get so many people to his site that advertisers will notice, and pay.

Right now, "profit's not a concern. It's getting traffic," Britton told me. Remember that kind of thinking from the first Internet bubble? Social media have multimillions of users. Twitter has raised more than $100 million from T. Rowe Price, Benchmark Capital, and other big investors, and a new generation is inspired.

"Once I have a million users a month, I can turn on the advertising feed," Britton said. "Once you have search traffic, you have revenue. This is how we get that audience."

Britton is a Plymouth Whitemarsh High School ('96) and Pitt ('00) grad who worked for a string of Web companies, first in New York, where he started at early social-media site TheGlobe.com, then in Southern California, where he founded and still owns, among other things, www.SiteLauncher.com, "which is spitting out cash."

He plans to return to Philadelphia this fall to run Sency and live downtown with his lawyer-girlfriend, a few blocks from his parents. His father, Robert Britton, is chief financial officer of the Philadelphia-based law firm Post & Schell.

"This is about the land grab for Web traffic," said Burt Breznick, business-development executive with Adchemy Inc., a Los Angeles online-marketing firm. Breznick knew Britton at Pitt and has followed his career in L.A.

It's not unusual for Web-savvy people to build simple widgets that attract townfuls of users and tens of thousands of dollars in ad sales a month, with little maintenance, Breznick says.

"What Evan is talking about is the next big thing," he concluded, correcting himself: "It's the thing today."

Unreal people

We don't know what kind of Christmas shopping season awaits the nation's battered retailers.

But m.Cellufun.com, a New York-based online time-wasting "mobile social-gaming community" backed by Boston-based Longworth Capital, says visitors have paid for 2.5 million "virtual transactions" since Cellufun started making them available in July.

That includes 750,000 purchases of $4 designer dresses and other virtual clothes for online avatars (little electronic people); 625,000 "flirts and greetings," including kisses for a nickel; one million "game-related items," and more than 100,000 items for "virtual pets," including $15 dragons that never leave your compact screen.

It's a sign of tough times that users buy "virtual" items that "may be out of reach in the real world," said chief executive officer Neil Edwards in a statement.

At least he can still tell the difference. Even if his customers can't.