Paul Volcker is worried about something worse than inflation

Volcker, 91, is aghast at how Americans no longer trust in government, media, science, or anything else. He chastises Trump for exacerbating the problem.

NEW YORK CITY — When Paul Volcker listens to President Trump bash the Federal Reserve, he grimaces, but he is not surprised. Volcker, the tall and revered former Fed chair, has personally witnessed more egregious examples of presidents demanding that interest rates stay low.

In the summer of 1984, when Volcker was Fed chair and in the midst of the painful process of trying to get inflation under control, President Ronald Reagan summoned him to the White House. Instead of meeting in the Oval Office, Volcker says in a new book that he was escorted into the library, where Reagan sat alongside Chief of Staff Jim Baker.

"The president is ordering you not to raise interest rates before the election," Baker said.

Volcker says he was "stunned" at Reagan's brazen attack on the Fed's independence. He was concerned because the central bank was not planning to raise rates at the time, and he did not want Reagan to think the library meeting had influenced policy. The scene was described before in Bob Woodward's book on Alan Greenspan, and Volcker is now giving his firsthand account of it at a crucial time for the Fed.

"I walked out without saying a word," Volcker writes in a book that is coming out this month, adding that he thinks that the library was chosen for the meeting because it "probably lacked a taping system."

■

Trump has called the central bank and current chair Jerome Powell "loco," "crazy," and "my biggest threat" for gradually raising interest rates, but the president has yet to summon Powell to the White House to discuss it in person.

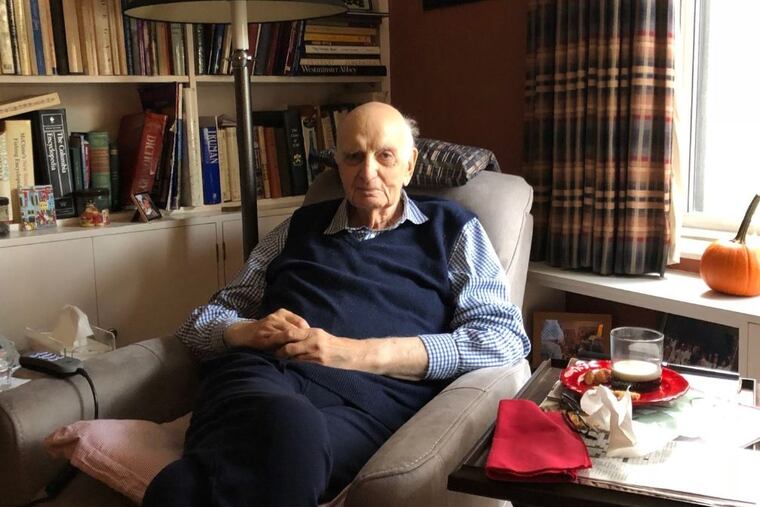

"My message to Chairman Powell is be strong and follow your instincts," Volcker said in an interview in the apartment he bought in the 1970s on Manhattan's tony Upper East Side. "Given all the other things Trump says, I wouldn't be too concerned."

Volcker says the Fed was under more duress than now in the early 1950s, when the Treasury pressed the central bank to keep rates low to make World War II debt payments more sustainable, and in 1979, as inflation spiked and Volcker dramatically hiked rates. In his book, he also shares that, in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson urged Fed Chair William McChesney Martin Jr. to keep rates low because raising them would "amount to squeezing blood from the American working man in the interest of Wall Street."

As the Treasury staffer responsible for monetary policy, Volcker was in the room when Johnson made his demand, and he remembers Martin refusing to yield. Johnson then took a different tactic, saying that he was having gallbladder surgery and that surely the Fed chair would not want to act while he was in the hospital. Martin ultimately waited to raise rates until Johnson left the hospital.

■

At 91, Volcker is about to publish Keeping at It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government, a book he cowrote with Christine Harper, the editor of Bloomberg Markets. It is partly a memoir of how a middle-class New Jersey boy born during the Great Depression ended up in the highest echelons of power in the White House and Fed. But it is also an urgent call for America to get its act together as he warns of partisanship and greed that could destroy the nation's ability to lead.

As the conversation turns to the central theme of his book, Volcker suddenly sits up in his heavily padded chair by his favorite window in his Manhattan apartment and points at me to make sure I write this down.

"We have a serious problem in this country," says Volcker, who is fighting cancer. "Here I am trying to defend government in the midst of a world that doesn't respect it."

Volcker is aghast at how, he says, Americans no longer trust in government, media, science, or anything else. While he acknowledges the erosion of trust has been going on for years, he chastises Trump for exacerbating the problem.

"I hope we're at the bottom," he says, adding he hopes "we'll begin clawing our away back, if not in this election, then in the next election."

■

People still come up to Volcker on the street to thank him for "saving our country" from inflation in the 1980s, when he took interest rates above 15 percent and caused a recession in an effort to tame double-digit inflation. He is not concerned (much) about inflation now. But he is terrified by how the U.S. government seems unable to do basic functions such as keeping up infrastructure, as well as the fact that few young Americans are entering public service.

"These days, college students interpret 'doing good' as going to law school and making $200,000 a year when they get out of law school," Volcker said, shaking his head.

He has taught numerous courses over the years at Princeton, where he graduated from in 1949 and wrote his prescient senior thesis on how the Fed should not cave to political pressure, in an effort to encourage more people to enter government.

Volcker devoted most of his adult life to public service, starting with a stint in the Kennedy administration and then working in some form with almost every administration — Republican and Democrat — that came after until Trump. He admits that he had a "guilty conscience" about not spending enough time with his two children, but he felt that his country needed him.

■

Most in Washington still view the former Fed chair as a centrist Democrat, especially after he endorsed Obama for president in 2008, but Volcker insists he has been an independent for three decades.

"My ideology is the importance of good government. That is not a popular ideology," he says at his home with his wife, Anke, and a nurse. "Good government has become a curse word. When I was a kid, it was a good word."

Volcker does not see much to compliment Trump about. He says that the president's signature economic policy — the tax cuts — was a huge mistake and that the "only purpose I can see is to try to squeeze Medicare and medical expenses and Social Security" now that the deficit is higher.

■

When it comes to the Fed, Volcker says that he hears a lot of the right things from Powell, who took over as chair in February, almost 30 years after Volcker left. But Volcker thinks that the Fed made a big mistake by announcing a 2 percent inflation target. By law, the Fed is supposed to keep prices stable, but the central bank does not need to define that with a specific figure.

"They made up the 2 percent number," Volcker says, his voice rising in frustration. "One of the reasons I wrote this damn memoir is I get upset when I hear them fighting over whether 1.75 percent is enough inflation."

He argues that there is no way to know with such precision what the inflation rate is, nor whether 2 percent is the right number that will keep the economy humming without overheating or crashing. To Volcker, central banking is an art, and it is dangerous to give the public a false perception that the Fed can fine tune so narrowly.

"The idea that the economy rests on whether the federal funds rate is 1.5 percent or 1.75 percent is just ridiculous," he said.

Volcker is always on the lookout for inflation. For him, it is still fresh how quickly it can spike out of control and how painful it can be to try to reign it back in. While he says he has heard from more people grateful for what he did as Fed chair, he has also been "cussed out" by a few Americans who are still upset he made mortgage rates go above 15 percent.

He is hopeful that Powell can keep inflation under control, but he urges today's Fed to remain vigilant.

"Two percent inflation isn't going to kill us. Even 2.3 percent for a few months won't necessarily send us into the dungeon," he said, "But be careful of 2.3 percent being OK and then they say let's let it go to 3 percent."

What he does know with certainty as he looks around his study filled with books, fishing mementos, and black-and-white photos is that he still misses the Brooklyn Dodgers and he never plans to go to Washington, D.C. again.

"I know one thing for sure. I no longer want to visit Washington, the city in which I gladly spent most of my career," he said. "It's all politics and lobbying now. It makes me ill."