An academic knowledge of elder care becomes a harsh, real lesson

Laura Katz Olson taught health-care policy for decades at Lehigh University and could rattle off the ins and outs of Medicare and Social Security.

Laura Katz Olson taught health-care policy for decades at Lehigh University and could rattle off the ins and outs of Medicare and Social Security.

But none of that prepared her for caring for her mother, Dorothy Katz, a Senior Olympics medal winner who developed Parkinson's disease.

Thrust into a long-distance caregiving role, Olson, 71, began grueling travel between Pennsylvania and Florida. Her mother's health failed with each passing visit.

"At first, I was convinced she could 'age in place,' as they say," Olson said. After her mother fell, then nearly died in a rehab facility, Olson moved her to Pennsylvania.

What Olson discovered in assisting her frail parent was at odds with her work as an elder-care expert. She could barely navigate the byzantine web of public and private insurance and services.

"As an academic, I looked for statistics and percentages on how Medicaid affects people. I had a lot of ideas on paper," she recalled with a rueful laugh. "They didn't seem real until I experienced them myself."

Olson's two siblings had died, so her mother's care fell to her entirely. Her work teaching at Lehigh was interrupted as Dottie Katz steadily grew incapacitated by Parkinson's-related dementia and a gradual loss of vision.

"You can only get your parent 10 hours of in-home care a week under Medicaid. Then the gap in service becomes real. I had to fill in the gap myself," Olson said of her visits to Florida.

"While everyone is pushing for at-home care, there's not enough coverage under Medicaid. In order to be eligible, you have to be nursing-home eligible," which means your elder relative's assets have been depleted.

In 2013, she moved her mother, now 93, into Gracedale, a county-run and subsidized senior facility in Nazareth, Pa.

Finding a facility for her mother and ensuring that her benefits stayed consistent shattered Olson's convictions and exposed irrationalities in government systems. Despite her expertise, Olson was ill-prepared to deal with the bureaucratic barriers imposed at every turn.

"I was surprised at how much every service is siloed," she said. "It's so burdensome as to be impossible. The VA? To deal with them [Dottie Katz's husband was a veteran] is a nightmare."

In Pennsylvania, the Department of Human Services threatened to cut off her mother's benefits because of one missing piece of paper - a bank statement that Olson had already submitted. "They just wanted paperwork again and again, to reinvent the wheel at every agency," she said.

Another office threatened to stop her mother's Medicare.

"The paperwork, the constant paperwork, that was surprising. And she has to reapply every year for Medicaid, which is a program for the poor."

As with any program for the poor, Olson said, "the agency assumes you're stealing and trying to get something for nothing. You have to prove everything - even if you're 93, blind, and have Parkinson's! The sting of it was unfathomable."

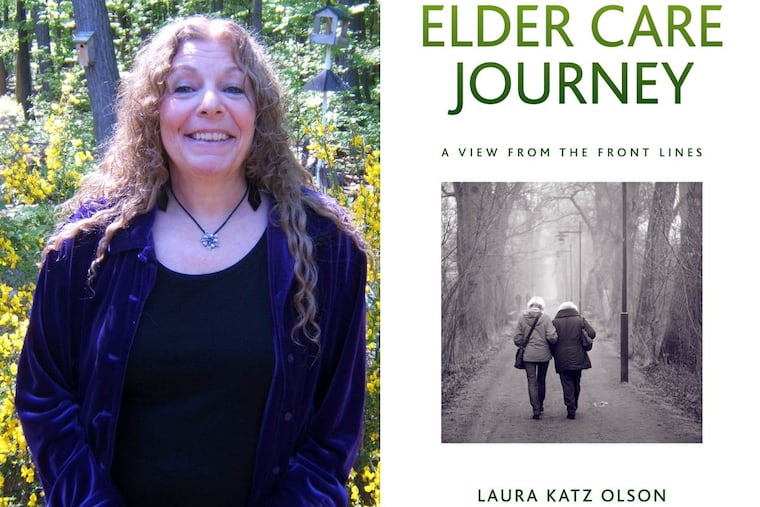

Olson's new book, Elder Care Journey, speaks to elders with functional limitations and the adult children helping them. The book documents the stresses and the manifold indignities in dealing with social-welfare agencies. Elders with limited financial resources often must rely on government funds for their basic care.

"I wanted to elucidate the obstacles confronted by other families attempting to navigate the complex and sorely inadequate programs serving the low-income aged," Olson said.

At Gracedale, Olson said, she has found a place providing decent care, so she no longer fears for her mother's health, safety, and well-being.

After reading her story, she said, "people coping with elder-care responsibilities should feel less alone in their struggles."

Along the way, Olson discovered that many nursing homes and elder-care facilities are owned by private equity firms or multichain conglomerates traded on public exchanges. "Their primary profit goals are at odds with the well-being of the people they are supposed to be serving.

"I wrote this book as catharsis, then I realized my experience isn't unique. There are serious issues with our long-term-care system. We spend billions of dollars of our federal and state budgets on long-term care and aging, and why aren't we getting better results?"

Almost half of private nursing-home revenue, 48 percent, comes from Medicaid and Medicare. About 80 percent of all home-care agency revenue also comes from those sources, said Ron Barth, CEO of LeadingAge, a consortium of nonprofits in the elder-care industry.

"The taxpayers are funding the long-term industries but aren't getting quality of care for their elders," Olson said.

She visits her mother every day and advocates for her.

Is that necessary?

"Yes, because I know the aides are overworked, underpaid, and overwhelmed. And even the best of them can't do it, because they have too many patients."

215-854-2808 @erinarvedlund