Apple's lost co-founder has no regrets

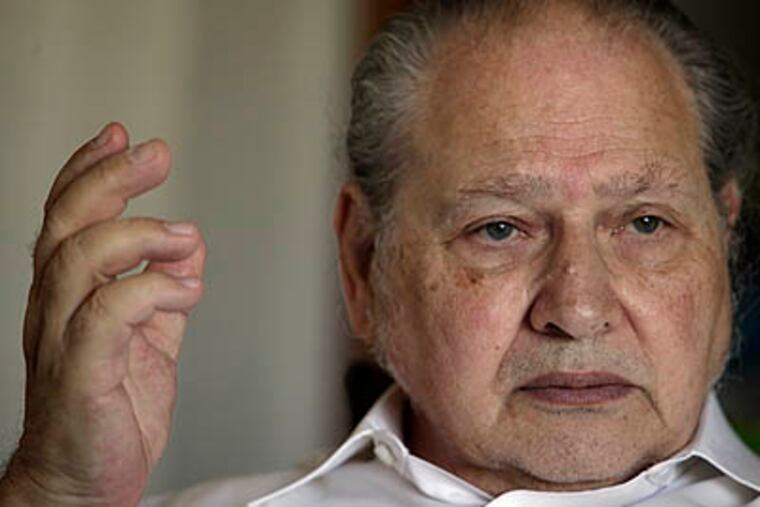

If Ron Wayne, now 76, weren't one of the most luckless men in the history of Silicon Valley, it wouldn't have turned out like this.

PAHRUMP, Nev. - It's usually past midnight when Ron Wayne, co-founder of Apple - colossus of the tech world, and Silicon Valley's most adored franchise - leaves his home here and heads into town. Averting his eyes from a boneyard of abandoned mobile homes, he drives past Terrible's Lakeside Casino & RV Park, then makes a left at the massage parlor built in the shape of a castle.

When he arrives at that night's casino of choice, Wayne makes a beeline for the penny slot machines. If it's the middle of the month and he has just cashed his Social Security check, he will keep battling the one-armed bandits until 2 a.m. Wayne is waiting to hit the jackpot, and he is long overdue.

If Ron Wayne, now 76, weren't one of the most luckless men in the history of Silicon Valley, it wouldn't have turned out like this.

He was present at the birth of cool on April Fool's Day, 1976: Co-founder - along with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak - of the Apple Computer Inc., Wayne designed the company's original logo, wrote the manual for the Apple I computer, and drafted the fledgling company's partnership agreement.

That agreement gave him a 10 percent ownership stake in Apple, a position that would be worth about $22 billion today if Wayne had held onto it.

But he didn't.

Afraid that Jobs' wild spending and Woz's recurrent "flights of fancy" would cause Apple to flop, Wayne decided to abdicate his role as adult-in-chief and bailed out after 12 days. Terrified to be the only one of the three founders with assets that creditors could seize, he sold back his shares for $800.

In a place where risk and innovation are part of the accepted equation of change, he became Silicon Valley's ultimate what-if story - Apple's iMadeAHugeMistake.

"If he'd had the foresight and, more importantly, the fortitude to hang on for another six months, it would be a completely different situation for him," said Tim Bajarin, an analyst for Creative Strategies, who has covered Apple since 1981.

Though Wayne remains an obscure figure whose story is rarely told - and then usually as a cautionary tale - he refuses to second-guess himself.

"I don't waste my time getting frustrated about things that didn't work out," he says. "I left Apple for reasons that seemed sound to me at the time. Why should I go back and 'what if' myself? If I did, I'd be in a rubber room by now."

Moments later, however, he turns somber. "Unfortunately, my whole life has been a day late and a dollar short," Wayne says.

With Monday's unveiling of the next-generation Apple iPhone, the company's other co-founders can expect to see their personal fortunes rise. Again. Since the release of the first iPhone two years ago, shares of Apple stock have more than doubled in value. After selling and buying stock over the years as Apple became a public company, Jobs' stake today is worth $1.5 billion. Wozniak's Apple holdings are not a matter of public record. Neither responded to interview requests.

But even a few million would go a long way here in the high desert, especially in a town so near the middle of nowhere that it didn't get telephones until the 1960s.

He was 42 and chief draftsman at Atari when he first encountered 21-year-old Steve Jobs, who was freelancing at the pioneering video game company after dropping out of college. Jobs had already met Wozniak, whose designs for a computer in a box he had seen at the Homebrew Computer Club, and now he was thinking about trying to sell them.

Wayne, who still lived with his mother, served as a frequent sounding board. "He was talking about the possibility of coming up with a personal computer," Wayne says of Jobs. "There were all these other things he wanted to do, so should he waste his time being focused on that? I told him that whatever he wanted to do, he could do it more easily with money in his pocket."

But he cautioned Jobs never to forget that the money was just a vehicle for creating things. "But he forgot," Wayne says now. "He probably won't like me for saying this, but I think he got caught up in the business of business. He became so enamored with succeeding at this stuff that he began doing it for the sake of itself. He began making money for the sake of making money. What can somebody do with $200 million that they can't do with $100 million?"

In Wozniak's autobiography, "iWoz," he recalls meeting Wayne and thinking, " 'Wow, this guy is amazing.' ... He seemed to know how to do all the things we didn't. Ron ended up playing a huge role in those very early days at Apple."

But in those early days, the free-spirited Woz was reluctant to commit himself, and it was driving Jobs crazy. "There were bits and pieces of the circuit for the Apple computer that Wozniak wanted to use in other places," Wayne recalls. "Jobs said, 'You can't do that. This is the property of Apple Computer.' He had an awful time with Woz because of the difference in their personalities."

Jobs quickly figured out that his budding partnership with Wozniak would require adult supervision, and asked Wayne to step in as the "tiebreaker." The two Steves came to Wayne's Milpitas, Calif., apartment, and after two hours of thrashing it out, the older man explained to Wozniak that the electronic architecture he was creating was critical to the ongoing existence of Apple. "He finally got the message," Wayne says. Jobs was agog.

"It was at that point he said, 'Let's form a company,' " Wayne recalls. Like a quarterback drawing a play in the dirt, Jobs came up with the idea of giving himself and Wozniak each 45 percent, the final 10 percent going to Wayne, who would mediate disputes between his headstrong partners. "That would resolve any problems forever and ever," says Wayne, who drew up the contract on a typewriter. There was no such thing as a word processor yet. They were about to invent it.

After the agreement was signed by all three, Wayne took it to the county registrar's office. "And Apple Computer was born as a company," he says.

Jobs immediately plunged the company into debt, agreeing to fill an order for 50 computers from the Byte Shop in Mountain View, Calif., then borrowing $5,000 cash and parts worth $15,000. Wayne was impressed with Jobs as a promoter - "His psyche was already fully matured," he says - but was astonished to discover huge gaps in his new partner's knowledge of electronics, such as aluminum's ability to conduct electricity. "I almost lost my uppers," says Wayne.

He also fretted that the Byte Shop - one of the first retail computer stores - "had a terrible reputation for not paying its bills." Jobs and Wozniak were essentially penniless, which meant that creditors would eventually come looking for Wayne.

"I just wasn't ready for the kind of whirlwind that Jobs and Wozniak represented," he says. "I felt certain the company was going to be successful; that wasn't the question. But how much of a roller coaster was it going to be? I didn't know that I could tolerate that kind of situation again. I thought if I stayed with Apple I was going to wind up the richest man in the cemetery."

It all might have turned out differently if Wayne hadn't suffered a traumatizing failure in business with a slot machine company he started five years earlier in Las Vegas. "That was before I realized I had no business being in business," he says. "It came to a disastrous end."

Twelve days after Wayne wrote the document that formally created Apple, he returned to the registrar's office and renounced his role in the company. When Jobs and Wozniak filed for incorporation a year later, Wayne received a letter asking him to officially forfeit any claims against the company, and he received another check, this time for $1,500. Taken together, the $2,300 he made as one of Apple's founders is almost exactly one-millionth what his shares would be worth today.

These days, Wayne sells stamps, rare coins and gold out of his home to supplement his monthly government check. When his precious metal clients drop by, he straps on a .38 caliber Police Special, just in case one of them tries to rob him. He has never owned an Apple computer, or any Apple product, and when Wayne recently bought his first desktop, it was a Dell. It's been years since he last heard from Jobs.

Wayne insists he has no regrets about the choice he made then, though he's careful not to say he would do the same thing again. "I'm as enamored with money as anybody else, and there are all sorts of things I'd love to do if I had it," he says.

After Apple, he spent two years creating the model shop at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, then was chief engineer at Thor Electronics in Salinas for 16 years. He holds a dozen patents, but he has never had the money to develop them into products.

"There were at least six times in my life when I really thought that I had the world by the tail," Wayne says, "when I thought, 'I have an invention here that's going to make me a fortune.' And six times it blew up. I don't know why; it just never happened. It's probably because I'm not the businessman I should be."

RON WAYNE:

- Designed original company logo

- Wrote Apple 1 computer users manual

- Sold 10 percent share in company for $800 (worth $22 billion today)

- Has never owned an Apple product

- Sells gold, rare coins and stamps from home in Pahrump, Nev.

(c) 2010, San Jose Mercury News (San Jose, Calif.).

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.