PhillyDeals: Protecting technology start-ups from media giants

The Internet was supposed to plug everyone in and bring us all close. Same for cable TV, regular television, radio, movies, and telephones.

Note: This article originally appeared April 10, 2011.

The Internet was supposed to plug everyone in and bring us all close. Same for cable TV, regular television, radio, movies, and telephones.

But each time, inventors and prophets of the new technologies were bought out and pushed aside by business empire-builders, backed by JPMorgan and other Wall Street banks - with government blessing.

These hard-driving bosses crowded out new competitors, and built national franchises to supply mass-produced information products and services at profitable prices, writes Columbia University professor Tim Wu, in his fast-moving history The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires.

At least the monopolists who ran AT&T and RCA, and the Jewish immigrant movie producers who dominated "Golden Age" Hollywood, self-censoring to please Catholic activists, felt an obligation to give the masses high-quality programs, Wu writes.

That trade-off enabled AT&T to suppress messaging and mobile technologies, just as RCA boss David Sarnoff delayed FM radio and stole blueprints from the early pioneers of television, Wu writes.

Eventually, disruptive new technologies win financial backing and crack the monopolies, sometimes with government help, as under President Richard Nixon. Then the cycle repeats.

Wu distrusts the Comcast-NBC Universal merger, the musical romance of AT&T and Apple (Wu contends their early partnership made them the arbiters of the music business), and the long-term intentions of Google.

Wu doesn't call for detailed regulation. He suggests a simple business separation among the owners of content, media systems, and the tools we use to read or watch.

That's not what's happening. Yet upstart attempts to challenge the media empires can be found, for example, in North Philadelphia.

Beyond DVDs

"Why can't we stream movies from studios to people, right now?" asks Tom Ashley, an Art Institute of Philadelphia graduate and sometime feature director.

His new firm, FlixFling, is based at his film-distribution business and soundstage, Invincible Pictures, in a block-long former mail-sorting facility at Fifth and Oxford.

Ashley and his staff built Invincible by buying new horror movies, documentaries, and other independent productions cheap, then promoting them through arthouse and multiplex screenings and DVD sales.

But the rapid decline in DVD use, as rental, cable, smartphone, and Internet-access services and Netflix made it easier to watch movies online, forced him to look at new ways of reaching fans.

"We saw inherent problems with the Netflix model" as it regards customer access, Ashley told me. "Netflix, Comcast, Apple, all these companies, they are very big on digital-rights management issues. They look at controlling the world, instead of opening it up.

"There's too many rules, too many restrictions. For example, to use any Xfinity pictures, you have to be a Comcast subscriber. I think it's a narrow approach."

Instead, FlixFling offers a "digital locker," streaming access to movies stored on public servers, at a few dollars per view.

"We haven't done any marketing, and we've already had 20,000 downloads of our iPhone-iPad [application], and close to 30,000 of our Google Android version," at a few dollars each, "and 6,000 registered pay-as-you-go users," paying a few dollars per movie, Ashley says.

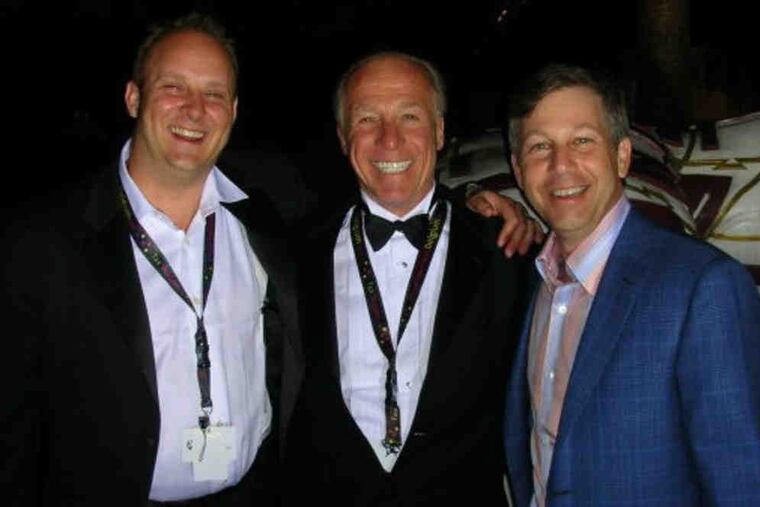

Ashley's financial backer is Brad Heffler, an accountant by trade, a sometime Hollywood investor and the founder of Claims Compensation Bureau, a 15-year-old Conshohocken firm that manages class-action lawsuits and other legal records.

"Creatively, he's amazing," Heffler says of Ashley. "He needed some business direction. I saw a good fit."

Can start-ups such as FlixFling challenge Netflix and the cable and video giants? "Consumers want content when they want it and how they want it - at the lowest price," says Tom Ara, entertainment-industry lawyer at the Los Angeles firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips L.L.P. He has represented FlixFling in talks with studios.

"In the music industry, the record companies resisted, and they found 'resistance is futile,' to quote Star Trek," Ara said.

But Wu's book is full of attractive start-ups that were bought, exploited, or suppressed by the giants of each era. If FlixFling works, won't some media imperialist take it over?

"I see this as another opportunity to grow a small start-up company into a real player in the industry," Heffler told me. "I anticipate we'll be approached. But our goal right now is to grow it. And get a lot of subscribers, and have a place for independent filmmakers to show movies they can't get out [otherwise]" through today's media empires.