Hank Gathers' death 25 years later: Still no clear answers

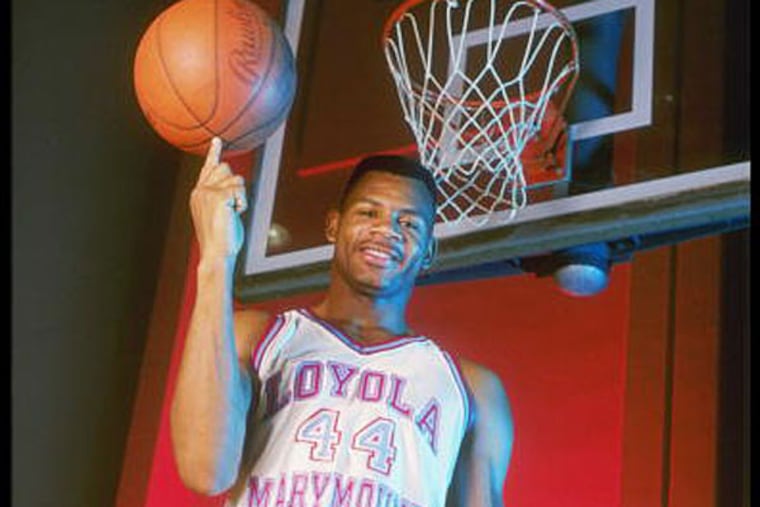

Basketball players in Philly cried that night. A man with seemingly endless streams of energy, who had just dunked off an alley-oop for the last of his 2,723 career NCAA points, part of an iconic Loyola Marymount scoring machine, dropped to the court in Southern California on March 4, 1990.

Basketball players in Philly cried that night. A man with seemingly endless streams of energy, who had just dunked off an alley-oop for the last of his 2,723 career NCAA points, part of an iconic Loyola Marymount scoring machine, dropped to the court in Southern California on March 4, 1990.

Even a quarter of a century later, there are no clear answers, even with genetic testing and significant treatment upgrades, about what the best way to protect Hank Gathers from sudden cardiac death would have been other than to get him to stop playing the sport he was born to play.

"This was his life," said T. Sloane Guy, chief of robotic surgery at Temple University Hospital, himself a former walk-on wide receiver at Wake Forest, who noted that he was the same age as Gathers, in medical school at Penn when Gathers died.

After Gathers' death, there were lawsuits and settlements involving Gathers and Loyola Marymount and a cardiologist. He had collapsed once before and been cleared to play, given medicine, which reportedly did not appear in his body in the autopsy.

The landscape has changed over the last 25 years. Genetic testing and treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has evolved. There is no question awareness of the seriousness of the condition has changed. This week, Guy and Daniel Dries, director of the familial cardiomyopathy program at Temple University Hospital, sat in an office just off North Broad Street and talked about the advances.

The condition, found in 1 in 500 people, causes the wall of the heart to be abnormally enlarged, dangerously slowing blood flow. Dries talked about how it can impact children in peewee leagues as easily as elite athletes. They aren't trying to scare anyone out of playing sports. Guy said sports was the most important training ground in his own life for his job leading a robotic surgery team.

"I would say there's an increased awareness in the community that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the leading cause of sudden and unexplained death in athletes," Dries said. "That it makes sense to require that athletes - or children before they participate in sports - get some kind of assessment or screening, usually from a physician, to try to detect that early."

Guy added that he worries about athletes who might be at risk but don't get screened for fear of being pulled off the court or the field. An important aspect of what's changed, Guy said, "is life expectancy. If it's recognized and treated appropriately, it's not unreasonable to expect a near normal life span in these patients. And that probably was not true 25 years ago. That's because of advances in medical therapy, in surgical therapy, in catheter-based therapies, etc."

If a parent carries the gene, there's a 50-50 chance a child will have it.

"It's our obligation, with new guidelines, to screen all first-degree relatives," Dries said. "What's changed in the last five years, in about half the cases we can now identify the gene mutation. And that makes it very easy. Then you can screen everybody for that mutation. If they don't have that, they're good to go. If they do have it, you make your recommendation."

Someone can still carry the gene, he said, and not have the disease in the heart yet.

"That's the funny thing about this disease," Dries said. "In the same family, people with the same mutation can present at different ages, and with different degrees of severity. We don't fully understand why that is. . . . Now that we have this new genetic testing that really makes it pretty easy - if we find the variant, you can actually go ahead and test people for that gene. Occasionally we'll find people in the family who have the gene variant, but when you do their EKG and echo[cardiogram], everything looks normal. But in the next couple of years - those are the people that we would follow very closely."

One of the hardest parts of his job, Dries said, is recommending that someone stop playing a sport. He related that he recently told a young hockey player whose father, sister, and aunt had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy that he should stop playing until he was tested for the condition.

When Gathers died, basketball grieved and continued on. The recreation center where Gathers grew up playing in North Philadelphia was renamed in his honor. It's away from the court, however, where maybe his impact was most important. Dries was in medical school in Wisconsin at the time. He didn't know much of anything about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, he said. As this became a central part of his own life's work, Dries has seen the evolution of treatment and understanding. This anniversary means something in his field.

At the time, Dries said, "I remember just reading about the death of a great, great ballplayer."

@jensenoffcampus