Joe Sacco unfolds 'The Great War' at Free Library

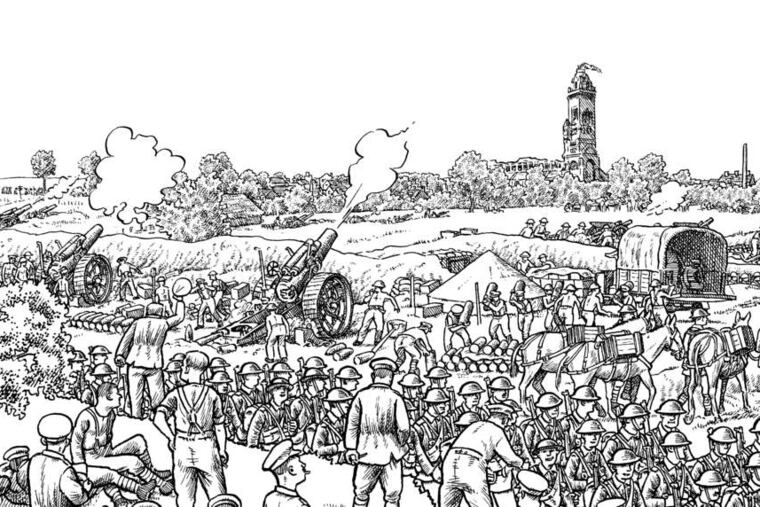

Joe Sacco's new book is an epic comic that depicts the horror of trench warfare during World War I. It's an accordion-style volume that opens into a single 24-foot-long panoramic drawing.

Joe Sacco's new book is an epic comic that depicts the horror of trench warfare during World War I. It's an accordion-style volume that opens into a single 24-foot-long panoramic drawing.

Called The Great War: July 1, 1916, The First Day of the Battle of the Somme (W.W. Norton, 54 pages, $35), its origins go back to the author and artist's boyhood in Australia.

Sacco, who will read at the Free Library of Philadelphia Thursday night, was born on the island of Malta in the Mediterranean Sea.

When he was an infant, his parents emigrated to Australia, where every April 25 is Anzac Day, commemorating the casualties suffered by Australian and New Zealand soldiers during the invasion of Gallipoli in WWI.

"They sacrificed so much blood there that it really entered the Australian national psyche," says Sacco, 53, author of masterful books of empathetic war-zone comic journalism, including Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde. "When I was a boy, they would stop class and play stories about World War I servicemen," he says, talking from New York this week. "And when I was reading about the First World War as a kid, the gas masks, the biplanes . . . all that stuff was somehow fascinating.

"I was also horrified because it became clear to me, even at that age, that huge armies were fighting for a few square miles, and that hundreds of thousands had died for almost no gain," he says. "In a way, this book is a way of redeeming that little boy's strange, voyeuristic interest."

Sacco studied journalism at the University of Oregon in the 1970s. While in Eugene, the cartoonist, who now lives in Portland, attempted to draw an epic centered on the Vietnam War, inspired both by heroes like George Orwell and R. Crumb and by homeless veterans living near campus.

A global perspective is in his blood. Sacco's parents lived through the siege of Malta by Italian and German bombers in World War II. He wrote about their ordeal in a comic later collected in 2003's Notes From a Defeatist. And he returned to the island with a growing population of African immigrants in The Unwanted, which appears in Journalism, a collection issued in paperback this year.

When he was growing up in Australia, Sacco says, "most of my parents' friends were European immigrants, all of whom had stories about the war. It was just in the air. It made me think about the idea of civilians in war, which is what most of my work has been about."

Sacco made his name with Palestine, for which he traveled to the Middle East in the early 1990s without an assignment or book deal. The stories introduced the signature Sacco style, in which the author - always wearing glasses, hiding his eyes - appears as an Everyman striving to make sense of a conflict with mounting human costs.

In Journalism, which includes sections on Iraq and Chechnya, Sacco is skeptical about the hallowed concept of "objectivity" in American journalism. In the preface, he quotes British journo Robert Fisk, who advises: "I always say that reporters should be neutral and unbiased on the side of those who suffer."

In the 1990s, a roommate in New York named Matt Weiland thought it would be a great idea for Sacco to draw the Western Front. Fifteen years later, Weiland, now an editor at W.W. Norton, brought it up again, using Matteo Pericoli's Manhattan Unfurled as a model.

Sick of war, Sacco's "first inclination was to say no. But then I thought about how much I've thought about World War I. I said, 'I'll do this if I can figure out a way to not make it static.' I'm a cartoonist, so I need a narrative. And then I thought of the Bayeux Tapestry, and I realized it could be done."

That tapestry is a 230-foot-long embroidered cloth that dates to the 11th century and depicts the Norman Conquest of England. "It shows you can tell something chronologically with one image. You basically read it, left to right."

As you do with The Great War. The drawing begins with Gen. Douglas Haig taking his morning constitutional, and ends on the afternoon of July 1, with soldiers burying some of the more than 21,000 British troops killed in the first day of the battle near the Somme River in France. More than a million men total eventually died in that battle, which raged into November.

The drawings, which Sacco drew by hand in eight months, with no computer assistance, is wordless. Time unfolds in slow motion as you turn leaves that detail Allied preparations and artillery barrages that failed to soften up German defenses, and left Allied soldiers sitting ducks as they marched into no-man's land.

There's an essay by historian Adam Hochschild and annotation by Sacco, pointing out details like an Indian cavalry regiment in the surprisingly horse-powered war, or soldiers given their food and rum ration before marching to their deaths.

Sacco's work concerns "thinking about the past as an organic part of the present," he says. Looking back at World War I is relevant in part because of the way it ushered in the modern age.

Much more than the next World War, the Great War's justification was widely called into question. "And a lot of it has to do with the way it was fought," Sacco says. "People pounding each other over a few square miles. And for what gain exactly? People wondered why it was fought, what were the reasons. It's definitely the place where the 20th century starts."

AUTHOR EVENT

Joe Sacco, "The Great War"

7:30 p.m. Thursday, Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St. Admission free.

Information: 215-567-4341 or www.freelibrary.org

EndText