The mystery of Michael Brooks

Maybe the mystery begins in an old anecdote from another continent, in what a man does and does not say about himself, even to his own flesh and blood. It has been nearly 25 years since Kevin Davis stepped off an airplane in France to visit his friend Michael Brooks, and what he remembers most clearly about the last time he saw Brooks was how little the people there knew about him. Those people included his friend's twin sons.

Maybe the mystery begins in an old anecdote from another continent, in what a man does and does not say about himself, even to his own flesh and blood. It has been 20 years or so since Kevin Davis stepped off an airplane in France to visit his friend Michael Brooks, and what he remembers most clearly about the last time he saw Brooks was how little the people there knew about him. Those people included his friend's children.

Brooks had played professional basketball in Limoges and near Paris from the late 1980s into the mid-1990s - well removed from his career at La Salle College (now La Salle University), where he and Davis had grown close. Davis spent several days there with Brooks and his family, and he left with a memory that has stayed with him since.

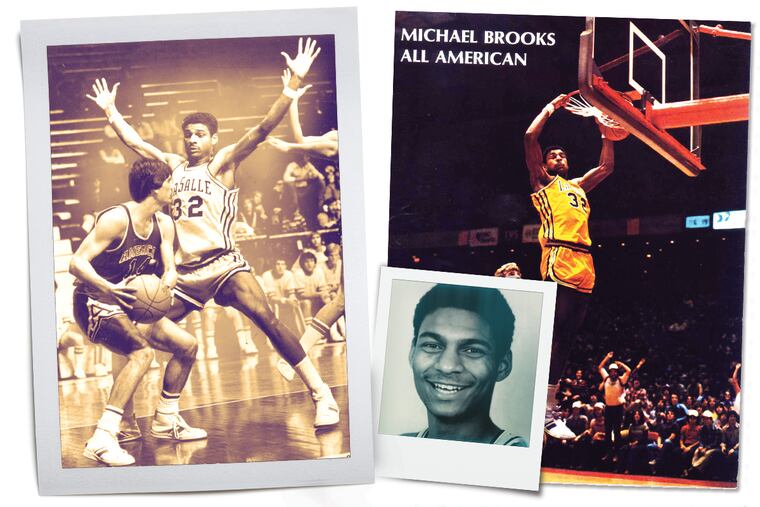

Brooks had been a remarkable college basketball player - a member of the all-American team, the leading scorer in La Salle history at the time of his graduation. He had been selected to the 1980 United States Olympic team. He had played six years in the NBA. Yet his accomplishments never came up in conversation during Davis' time in France, and Brooks' children - he had four at the time - never betrayed any awareness of them.

"They didn't have any sense," Davis said, "of who their father was."

Big Five Olympian

Michael Brooks has long been part of the answer to a trivia question that became relevant again last month, when USA Basketball revealed the roster for this year's men's Olympic team: Which former Big Five players have been chosen for the Olympics? There is Villanova's Kyle Lowry this year. There was St. Joseph's Mike Bantom in 1972. And there was Brooks in 1980, the year that the United States boycotted the Moscow Games, on orders from President Jimmy Carter, to protest the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

This was supposed to be a story about Brooks and 1980. This was supposed to be a chance, with the benefit of 36 years' perspective, to have him discuss what it was like to be an Olympian with no Olympics. Brooks apparently had no interest in that discussion. A coach with the Blonay Basketball Club in Switzerland, he did not respond to three calls to his cellphone, two interview requests to his personal email address, and one email request made through the club.

If his reticence were merely another example of an ex-athlete not wishing to speak to the media, it wouldn't be worth noting here. But Brooks has cut off virtually all contact with his alma mater, with former teammates, with anyone once or still affiliated with Philadelphia basketball. "He's Howard Hughes," La Salle athletic director Bill Bradshaw said.

He gave a phone interview in 2014 to a writer from a website that covers Brigham Young University athletics, for a feature about BYU's 108-106 triple-overtime victory over the Explorers in 1979 - a game in which Brooks scored 51 points. There was no available indication that Brooks has spoken publicly since.

When he was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame in 2013, he did not attend the ceremony. La Salle's sports information office didn't have updated contact information for him. Davis tried to get in touch with him on my behalf through Brooks' family and got nowhere. Over the years, various La Salle administrators have reached out to Davis, asking him to try to persuade Brooks to come back to campus, to acknowledge the accolades, to see his awards and photos on the walls of the Hayman Center, La Salle's athletic headquarters.

"He never would agree to come back to the city," Davis said. "I have no idea why."

Out of West Philly

Brooks will turn 58 in August - the son of an African American father (who left the family when Brooks was in ninth grade) and an Italian mother. He blossomed late at West Catholic High School, playing in the shadow of a more-heralded schoolboy legend, Gene Banks, of West Philadelphia High. At La Salle, though, he was a superstar upon arrival, a dynamic 6-foot-7 forward who finished his career with 2,628 points.

A terrific performance at the 1979 Pan American Games - where he led the U.S. team to a gold medal and earned the everlasting respect of its head coach, Bob Knight - lifted Brooks into the national consciousness. He averaged 17.4 points and 6.1 rebounds a game, serving as the feel-good counterbalance to Knight, who embarrassed himself and the country by allegedly assaulting a Puerto Rican police officer. For the next year, Knight became Brooks' public champion, giving Brooks' candidacy for the Olympic team more credibility with its head coach, Dave Gavitt.

"He was as good a kid as I ever coached, and he was as good a player as I ever coached," Knight said in a recent phone interview. "If I picked the top five kids in my career, Brooks would be one of them."

Carter had threatened in January 1980 that the United States might boycott the Games. So Brooks spent the four months ahead of the May tryouts knowing that, even if he made the Olympic team, it was possible, even likely, that he would not play.

"I'm one of those who very much hopes that the Olympics aren't canceled," he told the Daily News' Tom Cushman that January. Still, the uncertainty didn't appear to preoccupy him. Bradshaw was in the midst of his first tenure as La Salle's athletic director then, and one day after basketball season had ended, he glanced out his office window to the university's natatorium, where an intramural water polo match was taking place. There, bobbing in front of one of the goals, was Brooks.

"His smile lit up a room," Bradshaw said. "He was very engaging. He was a student when he was here, a student's student. People loved Michael."

The boycott became official on March 21, 1980. "All of us were disappointed for him because he was such a great player and teammate," said Air Force assistant coach Kurt Kanaskie, a guard on the 1979-80 La Salle team. "He certainly deserved to have that opportunity to represent his country."

Instead of competing in Moscow, the team toured the United States in June, going 5-0 in games against NBA standouts, then beating the 1976 U.S. Olympic team for good measure. Over that series, Brooks, the team's captain, was also its leading scorer (13.2 points a game), and he shot 51 percent from the field.

Perhaps just making the Olympic team was the most important thing to Brooks, however. When he did, he told reporters that he felt a sense of happiness and relief. He had played through a painful leg injury during his junior season, and he felt that people had looked at him differently, that they had doubted his talent and desire. Now, he had a measure of validation.

"Now," he said, "maybe those same people who turned their backs will turn around and face me [and] say, 'You're a player.' "

Foreshadowing

The first and best clue behind Brooks' self-imposed isolation is that he did it once before. The San Diego Clippers had taken him with the ninth pick in the 1980 NBA draft, and his first three seasons with them were promising: He averaged 14.1 points and 6.5 rebounds, and he did not miss a game. Then, on Feb. 4, 1984, he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee, and in early 1985, he vanished for 19 months. Friends, media, peers - no one heard from him during his rehabilitation. The Big Five inducted him into its Hall of Fame. He skipped the ceremony.

"I felt like I was on the outside looking in," he said in an interview with the Daily News' Phil Jasner in October 1986. "I would watch NBA games on television and say, 'I used to play against those guys.' It was something I had to do alone. . . . Michael had to do it alone."

Does he feel the same way now? He appeared in just 26 NBA games after the ACL tear, then played professionally in France for eight years. Did he lose part of himself when he lost his NBA career?

"That could be the missing piece," Bradshaw said. "His identity was basketball."

Davis has his own theory.

"I think when you become what he became, which was an incredible star, your world and your life become so scrutinized that you live under a magnifying glass," he said. "He wasn't comfortable in that environment. Who knows? There were probably some other issues he was battling. Having a mother who was white and Italian? Guess what, people had their issues with that. Michael's way of living his life in the limelight was shutting it all out by stepping away from that world. I think that was the only way he felt he could have privacy in his own life."

But these are guesses, grasps at the truth, for this is a mystery that only one man can solve, and there is no sign he wishes to solve it.

"I very much appreciate the opportunity to say something about Brooks," Bob Knight said the other day, "because I've been trying to find him just to see how he was doing." Then he hung up the phone, one more person hoping for a sense of who Michael Brooks is now, one more person coming up empty.

@MikeSielski