'Shining lights in the public schools'

Kristian Ali is a young dynamo from South Philadelphia whose personal story inspires her students to strive for more. Craig Carracappa built a well-regarded cinematography program from scratch.

Kristian Ali is a young dynamo from South Philadelphia whose personal story inspires her students to strive for more.

Craig Carracappa built a well-regarded cinematography program from scratch.

Margery Willis makes tough teens fall in love with 19th-century literature.

All three are excellent educators - emblematic of 63 Philadelphia School District teachers being honored by the Lindback Foundation on Tuesday for their talents.

In a school system in crisis, classroom triumphs often get lost in the shuffle.

But "there are a bunch of shining lights in the public schools," said David E. Loder, a trustee of the Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation, which is awarding the $3,500 prizes to high school teachers at a Tuesday afternoon ceremony at the Prince Music Theater. "In spite of all the stuff that they can't control - the budget cuts, the change in direction - look at all the amazing things that still go on daily in many schools."

'Definitely a challenge'

Four years ago, Kristian Ali was 22, a few years removed from her own Philadelphia high school experience. She was a newly minted educator thrown into teaching English to middle schoolers at FitzSimons High, a boys-only seventh-through-twelfth grade school.

She was terrified. Her students weren't sure she would return after winter break.

"It was definitely a challenge," said Ali, a graduate of Germantown High and West Chester University. "A challenge to earn their respect. A challenge to get them to do the work I put in front of them."

Eventually, she convinced her students she was there for the long haul. She told them about her own experiences - she often jumped from school to school when she was a child.

"I said: 'I live at home with my grandfather. I'm not that much different from you, only older,' " Ali said.

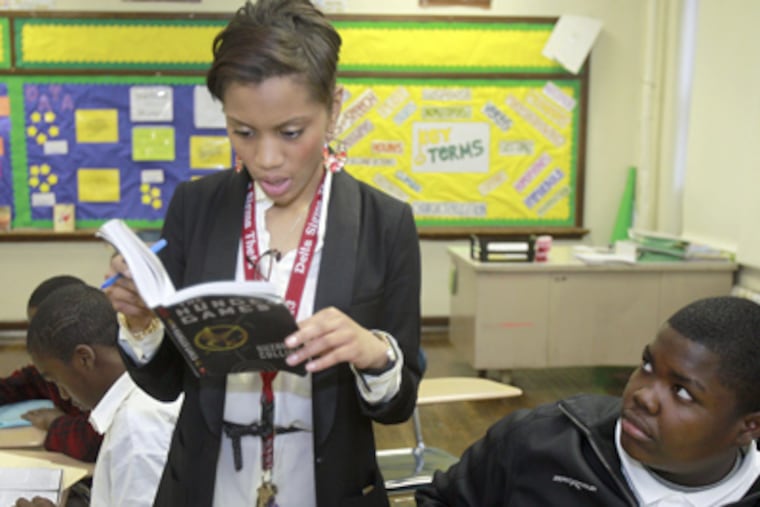

Her students may identify with Ali, but make no mistake: She is in charge of her classroom. On a recent morning, rows of seventh-grade boys listened to her intently, hands shooting up when Ali asked them probing questions about the young-adult novel The Hunger Games.

"Warning: We work hard in this class," a poster at the front of her classroom read.

"Every day, they leave my class and say, 'I'm tired,' " Ali said, smiling.

She has established herself as a strong presence in her building, working as FitzSimons' lead English teacher and its Middle School Academy lead teacher.

Navigating the Philadelphia School District's bumpy path of the last few years has been tough at times. In her short career, Ali has had to cope with the fallout of budget cuts and curriculum changes. FitzSimons is one of eight schools closing in June, and she must find another job in the district for the fall.

But Ali loves it, even with the bumps.

"This year, we can eat lunch with our students," she said. "I love sitting with them, just getting to know them. Just talking. I love getting them to trust you and getting them to want to learn."

'The universe told me'

Craig Carracappa never dreamed of becoming a teacher.

For years, he had a high-flying career directing large-scale corporate events, working on shows for 100 to 10,000 people across the country and around the world.

But then came the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and Carracappa's industry tanked. He moved on to become director of audiovisual services at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Then, in 2004, he answered a Craigslist ad. The Philadelphia School District wanted a cinematography teacher.

"The universe told me I was to become a teacher," said Carracappa. "It's absolutely what I'm supposed to be doing."

Eight years ago, Carracappa established the cinematography program at Communications Tech High, a school in Southwest Philadelphia that accepts students from around the city.

He built the program, making an empty room with only a single battered VHS recording device into a state-of-the-art studio with sophisticated cameras, wireless microphones, a teleprompter, and other equipment. (The money to pay for it comes from federal Perkins Grant dollars available to vocational programs, not the district's general fund.) Carracappa wrote the curriculum now used in other city schools.

His students write scripts and create storyboards. They learn how to make documentaries, news programs, and commercials.

As seniors, they take a NOCTI (National Occupational Competency Testing Institute) exam. This year, every one of Carracappa's students passed and is certified to work in the television-production industry.

"That gives them a leg up," Carracappa said. "They have skills that serve them well."

He pushes his students, who call him "Cap," but they respect him.

"They call me hard but fair," he said. "If you don't do any work, you won't pass, and they know it."

Teaching in a career and technical program - also known as vocational education - isn't a glamorous job. Bureaucratic hurdles are frequent. And he's teaching an art form to students who may not have ever taken an art class.

Plus, "voc ed does not get the attention it should; we fight against that a lot," Carracappa said. But what he does is important, so he keeps going.

"The things I teach are life skills - not just how to make a production, but time management, discipline, planning," Carracappa said. "This matters."

'My favorite venue'

Margery Willis walked up and down the aisles of her third-floor classroom at Overbrook High.

"Like Zora Neale says, let your spark shine through," she told her 11th-grade English students, referring to a passage they had just read in the Zora Neale Hurston novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Justin Berry, one of her students, calls her "the best English teacher I ever had."

"She makes you think, she breaks it down - she's not just a teacher who says, 'Do this,' and that's that. She goes deep," Berry said.

That's exactly why Willis is back in front of a high school classroom. She began her career in the district, but then left to teach communications at Temple and Penn State. Eventually, she opened and ran a successful retail lighting business.

But four years ago, she felt it was time to return to the district. She chose Overbrook, her alma mater, one of the city's large comprehensive high schools.

"This was always my favorite venue," Willis said. "I absolutely loved high school teaching. This is where we need great teachers."

Willis views her students as her audience, "and every audience is different. There's so many varied levels, so many extenuating circumstances, and you want to meet them all."

Technology is at the forefront of her classroom, with students often working on laptops and building their own personal, protected wikis. Willis updates a class blog daily so students who miss work can keep up; her students often access their wikis via their own smartphones.

But all of the bells and whistles serve her core purpose - making students fall in love with what they're reading, classic American novels and poetry and other important works. And they do.

"They turn themselves inside out," Willis said. "I have kids saying, 'I loved Emerson,' or 'I loved reading the Declaration of Independence,' or 'I loved reading The Crucible.' "

It may look seamless, but for Willis, a National Board Certified Teacher, it's the hardest job she's ever had, harder even than running a small business.

And it's worth it, she said.

"I just love that a-ha moment, where a kid just gets it," Willis said. "You can see it in their faces. All of a sudden, it makes sense to them, and no matter what level kids you have, you can get to that moment. When I see a kid get to that point, it fills me up."

Yes, it's a tumultuous time for the school district, with daunting deficits and plans afoot to tear up and remake the entire system, Willis acknowledged.

"But it's a very exciting time," Willis said. "We have so many different ways to reach our kids."