Covering the undercovers

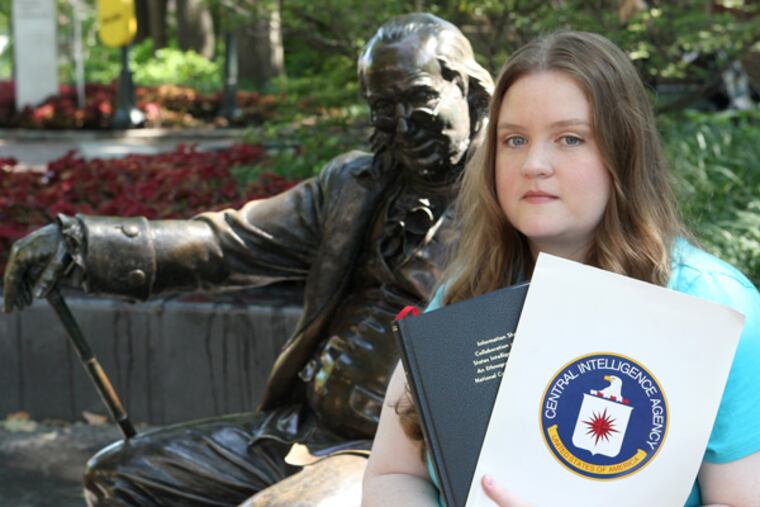

CIA fellow chronicles intense world of work that is counterterrorism.

Bridget Rose Nolan went through intense scrutiny to work as a graduate fellow for the CIA: an eight-hour polygraph, a 500-question psychological exam, probing interviews of family, friends, and neighbors, and, on her first day, a sweep of her car for explosives by guards toting AK-47s. All standard protocol.

But that was nothing compared to what Nolan, then a sociology doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania, would endure after deciding to study the agency and write her dissertation on it.

The CIA assigned Nolan to the National Counterterrorism Center in Virginia, formed after 9/11 to help the nation's 16 intelligence groups share, integrate, and analyze information. As a counterterrorism analyst, she pored over cryptic messages from a variety of sources and wrote reports for policy makers.

Nolan worked at the agency for three summers before proposing her examination of the counterterrorism center, a high-pressure world of code language and secrets as quirky as it was dark.

"Really, someone should study this place," Nolan said to another analyst over lunch one day. "Wait a minute. I should study this place!"

She set out to explore the culture of the terrorism center and how it, and its counterparts, share information - or fail to.

It was an idea that intrigued her Penn professors but soured her employer. She was bound by rules that required her to get permission for the study and anything she published.

The CIA rejected her proposal, and so began a three-year ordeal during which Nolan, a graduate of the Academy of Notre Dame de Namur in Villanova and Princeton University, went up against the agency.

And won, though it meant she had to resign.

"I sort of can't believe I pulled it off," Nolan said.

Born into an Irish Catholic family in Jenkintown, Nolan, 33, nurtured that grit at an early age when she competed nationally in Irish step-dancing. She qualified for the highest level of competition at age 12. For several years, she trained as long as six hours a day while soaring academically.

"It was rugged competition, and she prevailed," said her father, Frank Nolan, a lawyer. "When she sees something that's difficult, it just reinforces her intention that she's going to overcome it."

Nolan became interested in studying terrorism during the World Scholar-Athlete Games in Northern Ireland in August 1998, just before her freshman year at Princeton. She was representing the United States in the competition when terrorists exploded a car bomb in Omagh, County Tyrone, killing 29 people and injuring 220.

Nolan switched her major from chemical engineering to psychology, determined to explore the roots of terrorism.

The attack on the World Trade Center took place three years later, as she was about to begin her senior year. She climbed atop Princeton's Fine Hall, saw smoke from the towers, and thought: "I wanted to contribute to the fight against terrorism."

She went on to Penn for master's degrees in sociology and education and a doctorate in sociology. In 2005, she applied to the CIA's graduate fellow program.

The hiring process was lengthy and unnerving, she said. During the polygraph test, her interrogator accused her of having ties to the Irish Republican Army, then left the room several times for 20 to 30 minutes to consult with supervisors about her answers.

She also drew scrutiny on the psychological exam by answering "true" to the statement: "If I could go back and start all over, I wish I could have been born in the opposite gender."

She later wrote: "I had to spend at least an hour explaining to the male psychiatrist the disadvantages women face as the lower-status group in the gender hierarchy, and that I wouldn't mind having more power, status, and wealth, on average."

Nevertheless, she passed and began her career at the CIA in May 2007. She specialized in "Radicalization and Extremist Messages" within sub-Saharan Africa. Her days alongside analysts in high-walled cubicles were a lot more like the movie Office Space than Zero Dark Thirty, about the capture of Osama bin Laden.

Nolan was struck by how 9/11 "always seemed recent," an everyday topic. She also was overwhelmed by the large bureaucracy.

"I frequently found myself understanding the words, but not the meaning, of what people said," she wrote.

In 2009, she secured permission to begin her dissertation work. In addition to her own observations, she interviewed 20 fellow analysts, whose identities she protected.

Analysts, she found, were overworked, highly stressed, flooded with too much information - and not enough of what they needed. They felt compelled to report everything, which compounded the problem, she wrote.

"The concept of 'better safe than sorry' has its limits and can cause real damage," one analyst told her. "As a consequence of too much information sharing, key pieces of information sharing may be ignored."

But another confided: "No one wants to be the analyst that went home and tried to have a normal life, or have a normal weekend, and then come in on Monday and find out it was your account that literally blew up."

Four months into the interviews, Nolan wrote a proposal and submitted it to the CIA's Publications Review Board, which must sign off on all pieces written by current or former employees. In April 2010, the agency rejected it in part over security concerns.

"None of it was classified," Nolan argued. "A lot of it could be found on the Internet."

The agency also said the proposal was "inappropriate" for a current employee, interfered with the agency mission, would distract from her work, and "may not be understood by the public," she said.

Nolan submitted two revisions, the last of which was rejected in September 2010, in a letter the CIA marked classified.

After another year of wrangling, she quit her job, which gave the CIA less control over her writing. It could bar her only from releasing classified information.

"This whole career was being closed off to me," Nolan said. "But it just seemed like I was never going to graduate if I didn't do this."

She also hired Washington lawyer Mark Zaid, who frequently represents former agency employees seeking clearance to publish. On Sept. 27, 2011, five days after Zaid sent the agency a letter on Nolan's behalf, the CIA approved the proposal with "minuscule" changes, Nolan said.

'What's unfortunate about it is you had someone who wanted to remain an employee of the agency," Zaid said, "and they put her in an untenable position. She would have wasted all these years of her academic effort if she didn't resign."

In a statement, CIA spokesman Edward Price said current agency employees "are subject to rules designed to ensure their publications do not impair the author's job performance, interfere with CIA's functions, or adversely affect U.S. national security. As such, it should come as no surprise that an employee's resignation from CIA would nullify many of the concerns associated with a draft by a current CIA officer. That's exactly what happened in this case."

With approval in hand, Nolan wrote her 206-page dissertation. Through it all, her Penn professors supported her.

"The prospects of her succeeding were so enticing," said David Gibson, Nolan's sociology professor at Penn who is now at the University of Notre Dame. "The idea that she got access to this world was extraordinary. It obviously was a testimony to her incredible tenacity and gumption."

In an eerie coincidence, Nolan presented her dissertation at Penn on April 15, the day of the Boston bombings. She received her doctorate in May.

Nolan, who will teach at a writing center at Penn and at Bryn Mawr College in the fall, hopes the CIA will weigh her findings.

"Even though I had a negative experience in some ways," she said, "I still respect the place and I respect its mission."