Penn Law School to honor a life cut short

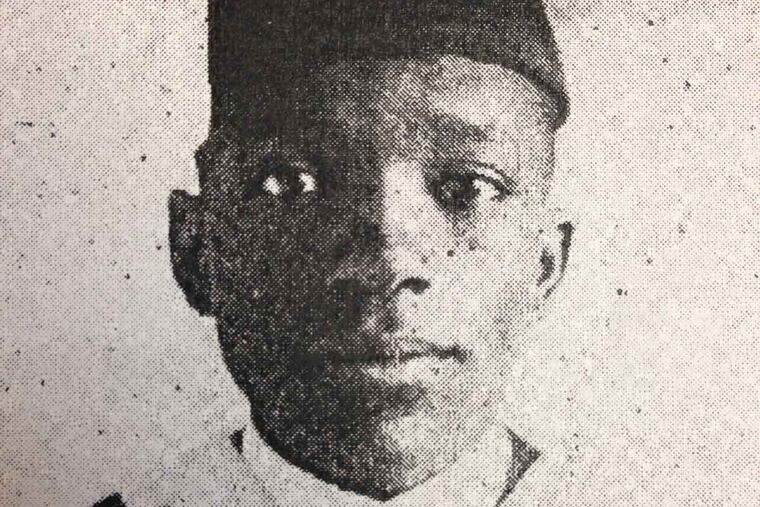

By all accounts, Theodore Milton Selden was headed for greatness. He graduated first in his class from the historically black Lincoln University and summa cum laude from Dartmouth College, earning two bachelor's degrees and admission to the exclusive Phi Beta Kappa honor society. Selden enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and was among the first African Americans to attend the prestigious school.

By all accounts, Theodore Milton Selden was headed for greatness.

He graduated first in his class from the historically black Lincoln University and summa cum laude from Dartmouth College, earning two bachelor's degrees and admission to the exclusive Phi Beta Kappa honor society. Selden enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and was among the first African Americans to attend the prestigious school.

Then came the July day in 1922 that ended everything. The 23-year-old, who had been working as a Pullman porter while attending school, was aboard a midnight train from Philadelphia to Atlantic City that derailed about halfway. His severely burned body was identified by a bit of gold - what remained of his Phi Beta Kappa key, found nearby.

With that, Selden - the seventh of eight children and the youngest son - disappeared into obscurity.

Now, more than 90 years after the young man's promise was cut short, Penn Law has announced that it will dedicate a plaque in his honor, as it has done for other notable students. The plaque will be unveiled in a ceremony Friday at the law school in front of members of his family and his fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi, and officials from Lincoln.

"When I received the call from [Penn] . . . and found out that my great-uncle went to Penn Law School, I was amazed," said Janet Selden, a retired Pennsylvania senior deputy attorney general.

Janet Selden, now of Wilmington, said she knew Theodore Selden had studied law somewhere because her father, a Lincoln graduate and former math teacher who received a master's degree from Penn, had told her he was happy she was following in her great-uncle's footsteps. His uncle, he told her, never had the chance to finish.

Penn told her that Theodore Selden finished his first year of law school and was ranked in the top half of his class.

"I got really choked up," said Janet Selden, who grew up in Yeadon and got her undergraduate degree from Pace University and her law degree from Howard University. "I felt, in some small part, I had pursued his dream."

Gary Clinton, dean of students at Penn Law, wishes he had thought of honoring Selden more than three decades ago, when, as a young law-school registrar, he happened across Selden's information while moving files. He thought it was odd for a student to die, and read a newspaper article about the circumstances.

"I was really intrigued," he said. "I thought, this was an impressive guy."

Then he put the file aside. But over the years, he frequently recounted the story of the brilliant student who died before his time.

Last summer, an alum asked him about a plaque, one of several hanging in the law school on Sansom Street, that honored John Lisle, a graduate who "gave his life for another" in 1915. Clinton researched Lisle and found that he drowned trying to save someone else. Then Clinton took notice of other law school plaques, all for white men. About 8 percent of the law school's students are African American.

He flashed back to Selden. Shouldn't there be a plaque for him?

"It just seemed to me that he deserved the same kind of attention," Clinton said.

He pieced the rest of Selden's academic life together:

Born in 1898 in Norfolk, Va. Graduated first in his class from Lincoln in 1919. Became a chemistry and physics professor at Lincoln for a year. Then transferred to Dartmouth for a second degree. Graduated second in his class. Won Dartmouth's Barge Gold Medal for original oratory for his piece titled, "The Third Emancipation." Near the end it states:

"Then if America has a weakest link, it must be made stronger. The modern Negro labors to accomplish this. He places emphasis upon rights, but emphasizes duty equally. He aims to deserve all he demands. May he, also, be granted all he deserves."

Among about 100 people to attend the ceremony will be Janet Selden's brother Basil, a New Orleans doctor who graduated from Penn's medical school, and Richard Green, interim president of Lincoln.

Green praised Penn Law and said he hopes the ceremony will be the beginning of a closer relationship between the schools.

"I would like to see other opportunities for current Lincoln students to have a relationship with Penn," he said.

Selden's plaque will hang on the second floor of the original law school building, the place Selden walked as a student nearly 100 years ago. It will read, "In Honor of Theodore Milton Selden . . . What Might Have Been?"

Grandniece Marguerite Selden Long Steele, a computer consultant for the Commonwealth of Virginia, is traveling to Philadelphia for the ceremony from her home in Richmond.

"It's quite an honor and a privilege for our family to have Penn Law recognize and honor him," she said. "Actually, it's also a way for our family to memorialize him."

Janet Selden said she wished she could have known him.

"He would have had influence on our family," she said. "It probably would have changed all of our lives."

Perhaps he will influence at least one mind.

"Maybe I could go to law school," Janet Selden's son, Ricardo Williams, a recent graduate of Clark Atlanta University, said to her after learning of his great-great-uncle.

Her son, she said, who is 24, had never expressed interest in following in her footsteps before. The experience of learning about Selden raised his consciousness, she said.

"Of course, you could go to law school," she told him. "Look at your great-uncle. He had those obstacles in his way, but he did it anyway."

215-854-4693@ssnyderinq