45 years after Vietnam, former enemies meet

Dennis Murphy spotted the young woman, standing on the first floor of Rosemont College's main building and looking around in awe. He thought he'd say hello.

Dennis Murphy spotted the young woman, standing on the first floor of Rosemont College's main building and looking around in awe. He thought he'd say hello.

It was Phuong Nguyen's first day on campus. She told Murphy, the Catholic college's admissions officer, that she'd just arrived from Vietnam to pursue her master's.

He'd been to Vietnam once, he told her.

To fight.

"My dad fought in the Vietnam War, too," she said.

For the North.

"It was a bit of a shock," recalled Murphy, who was shot five times and nearly died in that country.

The shock was just beginning.

Through a Skype call and later in-person meetings, Murphy and the student's father, Thu Nguyen, would discover they probably fought within 30 miles of each other. It isn't inconceivable they could have met on the battlefield.

Instead, they would meet 45 years later on a leafy suburban campus on Philadelphia's Main Line, two 65-year-old men who would put aside the past and forge a friendship through a young woman who bridged their worlds.

Nguyen's father told Murphy: "If I had had the right to choose, I would have chosen the pen over the gun."

Murphy knew he was destined for Vietnam. He had a low draft number. He enlisted in the Army in 1969, bent on getting an education that the GI Bill would help pay for.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Delaware County, Murphy was part of a devout Irish Catholic family. With six children, the Murphys were tight for money. He graduated from Monsignor Bonner High School, then hitchhiked to the local community college to take classes by day. At night he worked in a weaving mill.

He shipped out in August 1970, a member of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade of the Americal Division, and was stationed in the I Corp zone in the northernmost region of South Vietnam. The 20-year-old was made a grenadier, a launcher of explosives.

Murphy had been there six months on Feb. 12, 1971, when his unit got caught in a firefight.

One of his comrades was wounded and lying on a dirt trail, surrounded by jungle. A sergeant who tried to help was killed. Murphy tried next.

"I don't want to die, Murphy. Save me," he recalled his friend begging. Murphy grabbed the man and began dragging him when a bullet ripped through Murphy's ankle, toppling him. When he looked up, he saw three men in olive-green North Vietnamese uniforms within feet of him, their guns aimed. Another bullet struck his right knuckles and grazed his forehead. He took three more hits, two in his back and one in his thigh.

He knew he could not save his friend.

Murphy played dead, then slowly crawled to safety, whispering Hail Marys.

He spent weeks in critical care at a hospital in Japan, then six months at Valley Forge Military Hospital. His knuckles are scarred; his back has never felt the same. For his actions, he received the Silver Star and Purple Heart.

"I was very lucky," he said, tearing.

After he recovered, he earned his bachelor's in education at West Chester University and his master's in educational counseling at Villanova. He has worked at area colleges since 1977 and joined Rosemont in June 2014, two months before he met Nguyen.

Once a year, he visits with surviving members of his unit, Charlie Company, at Fort Benning in Georgia. But nothing has stirred his Vietnam memories like the encounter with the Nguyens.

Nguyen, 27, was working in publishing in Hanoi when she won a Fulbright scholarship to study the industry in the States. Her father, she said, was thrilled. He bore no deep resentment of the country he once battled.

She was beginning a master's program at Rosemont when Murphy disclosed his war involvement to her. Nguyen grew up seeing the impact the war had on her father.

He had been drafted in August 1970 and served as a reconnaissance soldier and deputy platoon commander.

Her father, she said, kept just two mementos from his five years at war - his olive-green uniform and the metal badge of a friend he had to bury. Nguyen recalls, as a 7-year-old, seeing her father don his uniform and cry. That was more than two decades after the war's end. He told her about his friend's death.

There was a bombing. The bodies of four soldiers were blown apart, including that of his friend. He put all the parts in a nylon bag and buried them in a common grave.

Her father wasn't the only family member scarred. Her mother lost an older brother in battle.

After the war, her father became a telecommunications executive. He has since retired and written a book about the industry.

Each year he gets together with men from his unit. Never had he met someone from the other side.

When Nguyen told her father about Murphy, "my dad was really excited," she said. She arranged for the men to Skype and translated the conversation. The call led to plans for a visit.

In July, Nguyen's parents flew from Vietnam and met Murphy in Rosemont's dining hall. The men walked arm in arm, Murphy nearly a foot taller than his new friend.

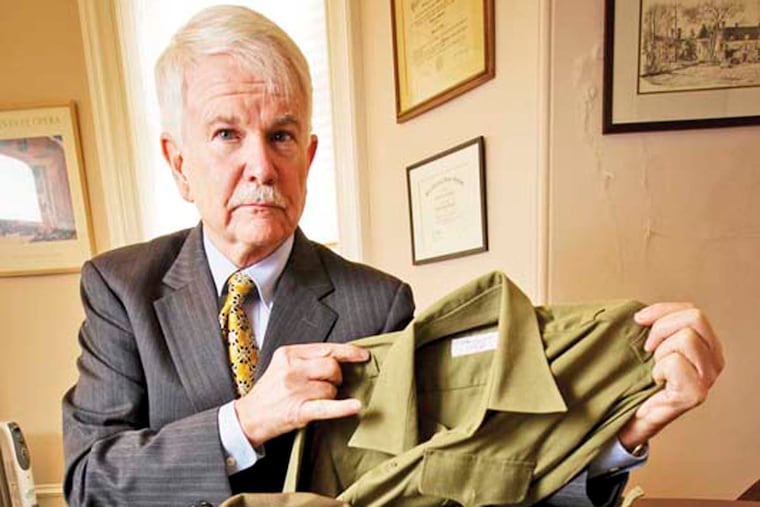

Her father gave Murphy a book, The Sorrow of War, a vivid account from the view of a North Vietnamese soldier. He also handed over his old uniform, wrapped like a present. He then put on the olive greens to show Murphy they still fit.

Something triggered an old emotion.

"Anxiety," Murphy said.

Nguyen's father would soon understand that emotion. On their second meeting, the Nguyens visited the Veterans Memorial in Delaware County and had dinner at the Murphys' house in Wayne. Murphy gave Nguyen's father his khaki Army uniform.

"The moment I received your uniform, I understood how hard it was for you to receive mine," her father wrote in Vietnamese by email to Murphy in November. "But after all, it helped me a lot. It made me feel that finally I could forgive the past."

Murphy's feelings evolved, too.

"Never would I think that someone who, I know, valued his green uniform . . . could part with such a priceless gift to a former enemy," Murphy answered to Nguyen. "As a Christian, it was what my God would want me to do. But your father was the role model. He brought me to a better place."

Murphy says the experience changed him.

"I never really thought about what they felt," Murphy said. "This has given me a different perspective."

Nguyen's father told Murphy he had used his uniform as a visual when telling his children what he experienced in the war.

"But I don't need it anymore," he wrote. "The meeting with you will be the story that I will tell from now on."

Nguyen, who wrote about her father and Murphy for a magazine-writing class, said she learned there was another side.

"I feel like we're more tolerant now," she said. "If these two soldiers after all they have been through can be friends, then everybody can be friends."

215-854-4693@ssnyderinq