Art | This artist defies categories

One of H.C. Westermann's most appealing qualities is that his art can't be pigeonholed, according to either how he worked or the themes that preoccupied him. He's remembered mainly as a sculptor and object-maker, yet he began his career as a painter. When he stopped painting on canvas, he continued to apply paint in ingenious ways to his three-dimensional creations.

One of H.C. Westermann's most appealing qualities is that his art can't be pigeonholed, according to either how he worked or the themes that preoccupied him. He's remembered mainly as a sculptor and object-maker, yet he began his career as a painter. When he stopped painting on canvas, he continued to apply paint in ingenious ways to his three-dimensional creations.

The lack of categorical guidelines forces viewers of Westermann's art to trust what they see and to rely on their powers of analysis to grasp the ideas and attitudes that he expresses. However, his art can be deceptive and difficult to decipher because it typically offers many contrasting facets.

It often appears superficially whimsical, yet its message is deadly serious. It can look naive, or like folk art, but Westermann was neither an art-world outsider - in fact, he was, and remains, firmly in the contemporary mainstream - nor an intuitive rustic. His sculptures and objects frequently display an obsession with, and mastery of, woodworking techniques, but they could never be mistaken for products of a hobbyist's basement workshop.

Westermann's art is so distinctive that, once one learns its hallmarks, it can't be mistaken for the work of anyone else. Besides what it reveals about the artist's life, it marks him as a rugged individualist with an affection for tools and materials, especially wood. His sculptures and objects are often over-built, as if to emphasize their status as hand-crafted objects.

All this is manifest in the traveling exhibition of Westermann's early work that has come to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The approximately 70 exhibits date from the late 1940s, when he was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, to the early 1960s, when he stopped painting to concentrate on three-dimensional work.

Organized at the Contemporary Museum in Honolulu, the show calls attention to the artist's early paintings, which are less familiar to museum-goers than the wooden constructions for which he eventually became celebrated. The paintings demonstrate that Westermann's signature mix of surrealism, modernist abstraction and cartoonish whimsy developed early in his career.

His art might look cute, or juvenile in some cases, but its worldview is dour, at times even misanthropic. In particular, it denounces the cruelty and foolishness of wars instigated by men too obtuse to comprehend the destructive forces they unleash. Westermann was radicalized by war - two wars, in fact - before that phenomenon became evident in the population at large.

The artist died in 1981, five weeks short of his 59th birthday. He served two hitches in the Marine Corps, four years as an antiaircraft gunner on the aircraft carrier Enterprise during World War II and about 19 months as an infantryman during the Korean War. His combat experience apparently persuaded him that, far from being noble, war was an unconscionable and brutish waste of human life.

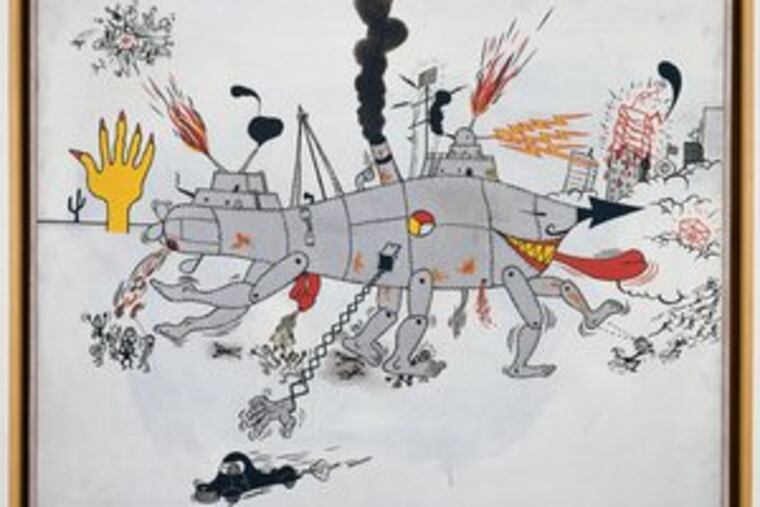

The paintings don't express this graphically, however, except perhaps for Destructive Machine From Under the Sea, painted in 1959. Even here, though, the anti-war message is wrapped in a comic mantle that reminded me a bit of Saul Steinberg. Westermann's anthropomorphic "machine," a combination of submarine and battleship, lumbers across the landscape, vaporizing a city and crushing people under its six feet. It's demonic, but capable of eliciting a smile or even a chuckle.

The antiwar message of The Storm is more subliminal, and conveyed primarily through a frightened horse that Westermann appears to have borrowed from Picasso's Guernica.

After World War II and again after the Korean War (he enlisted for both), Westermann studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. Initially, he enrolled in graphic and applied arts; after Korea, he switched to fine arts. In Chicago, he obviously became familiar with modern art, because he appears to have used a variation of Paul Klee's line-and-block abstract patterning to vividly decorate a small metal box.

Westermann didn't pursue modernism, however, as his sculptures and objects from the 1950s indicate. These are primarily symbolic and fetishistic, and often take the form of boxes or, in the most demonstrative example, of a gabled building.

This is Mad House, a structure inspired by Hermann Hesse's novel Steppenwolf. The building, which resembles a church or school, is said to symbolize a person vexed by conflicting impulses that he or she is unable to resolve. It contains multiple peepholes into an interior that contains painted images. Unfortunately, visitors can't get close enough to the sculpture to look in.

They can't help but notice, though, that the sculpture's fabrication is exaggerated. The wood is thicker than it needs to be and the joining and fastening are unusually prominent. This "over-built" quality reads as affirming the virtue of individual craftsmanship. Westermann further validated this philosophy by designing and building his own house and studio in Brookfield Center, Conn.

Two sculptures, more poignant than Mad House, are equally memorable. One is A Soldier's Dream, which consists of red glass panels set into a wooden frame that forms a vertical box. A brass human silhouette hangs inside, a detached leg lies on the bottom and a stylized flame sprouts from the top. The agonies of war couldn't be intimated more succinctly.

The other piece is Dismasted Ship, a stark existential commentary on the ultimate tragedy of life. It's little more than a hull with a tiny human figure lying on its deck. Unlike many of the other sculptures, it's devoid of animating color or the runic words and phrases that Westermann often uses to amplify meaning. It's just a hulk with broken masts, drifting or grounded, an apt metaphor for the human condition.

By the chronological end of this exhibition, Westermann is just getting up steam for the two decades of creativity that will solidify his reputation. Yet there's more than enough on view in the academy's Hamilton building to provoke, delight and perhaps befuddle anyone seeking to understand this fascinating artist.

Art | Barbed Humor

"Dreaming of a Speech Without Words: The Paintings and Early Objects of H.C. Westermann" continues at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Broad and Cherry Streets, through Sept. 16. The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays and from 11 to 5 Sundays. Admission is $7 general, $6 for seniors and students with ID, and $5 for visitors 5 through 18. Information: 215-972-7600 or www.pafa.org.

EndText