Clarifying why Trane matters

John Coltrane is not only, as Ben Ratliff argues in this profound book, "more widely imitated in jazz over the last fifty years than any other figure." He is also one of the most extensively written about. Publishing a new text on the saxophone legend requires an airtight rationale, and Ratliff has several.

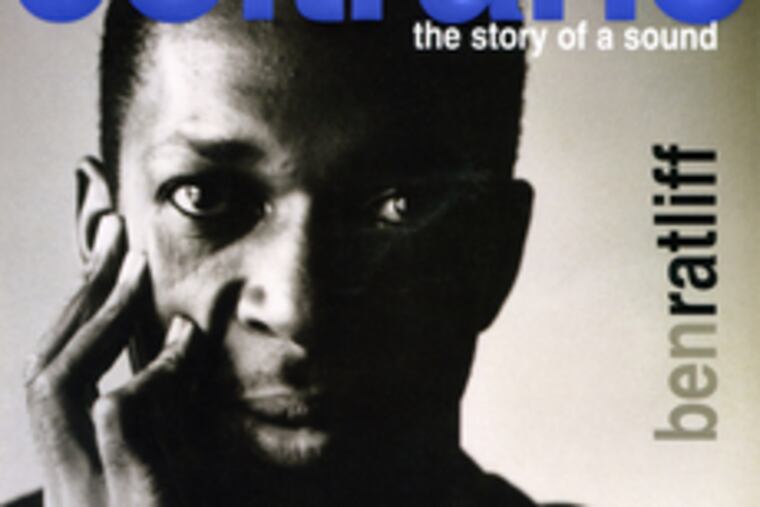

The Story of a Sound

By Ben Ratliff

Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

250 pp. $24

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by David R. Adler

For The Inquirer

nolead ends John Coltrane is not only, as Ben Ratliff argues in this profound book, "more widely imitated in jazz over the last fifty years than any other figure." He is also one of the most extensively written about. Publishing a new text on the saxophone legend requires an airtight rationale, and Ratliff has several.

Coltrane: The Story of a Sound succeeds as biography, but it is more a compact critical essay, an argument. Ratliff is less interested in praising a long-departed hero than in reaching conclusions about the "hundreds of microclimates" that make up today's jazz scene, a beat he has covered as staff critic for the New York Times since 1996.

At the same time, Ratliff looks at how a society understands, assimilates and mythologizes genius. "azz isn't an exercise book, or a father's record collection, or music as a closed-off thing-in-itself," he insists, opening the door to deeper questions about art and aesthetics, culture and politics. So in Ratliff's pages we read about Edmund Burke and Robert Lowell on the nature of the sublime. We encounter insights gleaned from Susan Sontag, Oscar Wilde and D.H. Lawrence, among others. We come to see Coltrane not as a demigod but as part of an environment, at a time of widespread artistic and political ferment.

Ratliff divides the book into two parts, building interest with cryptic lowercase chapter headings such as "best good," "you must die" and "who's willie mays?" Part 1 describes how Coltrane went from "a perfectly indistinct musician" in the mid-'40s to "unreasonably exceptional" by the time of his death from cancer in 1967. Meshing historical detail with keen music analysis and a storyteller's instinct, Ratliff packs Coltrane's career into a gripping 110 pages - from the early apprenticeships and Prestige albums to Giant Steps, A Love Supreme, and finally the visceral, "ecstatic" avant-garde music that stirs controversy to this day. The story itself is well known, but Ratliff doesn't merely retell it. Between the lines, he patiently builds a case about how jazz innovation works.

Part 2 is an equally vital "reception history" of Coltrane's music. It should be understood that John Coltrane was not "John Coltrane" while alive. He was not immediately revered; some never accepted him. Nonetheless, and through no conscious effort on his part, he cast a "heavy blanket of influence" during his life and after. In jazz, "entire careers have drafted in his tailwind," Ratliff writes. Beyond jazz, Coltrane inspired everyone from Iggy Pop to the Grateful Dead, Steve Reich to the Minutemen. His sound became "a metaphor for dignified perseverance," and the spiritual urgency of his late works made him an unwitting Black Power icon. Here in Philadelphia, his old stomping ground, T-shirt vendors hawk his image right next to that of Elijah Muhammad.

Ratliff is equally wary of the "bitter dogmatic reactions" to Coltrane's avant-garde period and the "thunderous credence" of those who hail it as his truest, most important work. The late-period music, in Ratliff's view, could be seen as "apodictic" art, an art of the "single, potent gesture" that resists all interpretation - a notion that gained popularity in the mid-'60s. To some, this music, in its severity and rejection of Western musical norms, embodied nothing less than the black freedom struggle itself. In the jazz press of the time, talk of Coltrane turned into "an ugly circle of irritation." Ratliff parses it with admirable evenhandedness.

The Coltrane legacy has sparked "general confusion and a forty-year critical breakdown," Ratliff contends. Correcting this - gently dislodging clots in the bloodstream of jazz appreciation and criticism - is the author's highest aim here. When Coltrane traveled light years in a decade and then died at 40, he didn't just leave a huge void; he skewed the very idea of artistic development, shaping the expectations we place on jazz musicians today. "The structural innovations of jazz really did slow down precipitously after Coltrane," Ratliff admits. "Yet the surrounding rhetoric traveled on and on and on, disembodied from its context, like a rider thrown headlong from a horse."

Ratliff is no water-carrier for Wynton Marsalis' pugnacious neoclassicism, but he takes pointed aim at the "future-mongering" he encounters elsewhere in the jazz world. The demand for perpetual newness is rooted in a "hippie myth" about jazz, he maintains; the less sexy reality is that the music "will advance by slow degrees." To speculate about the arrival of "the next Coltrane" is ahistorical: "It is the wrong question for jazz - hostile to it, or basically uninterested in it." Better to recognize the diverse bounty of talent under our noses.