Art: Africans in Mexico

A revelatory exhibition at the African American Museum shows their little-known influence on Mexican culture.

By the way they present art, museums encourage us to engage objects one by one and to consider their individual characteristics. This usually produces a purely aesthetic response to a work's formal qualities, without regard to its cultural ramifications.

Occasionally, though, an exhibition reminds us that art encodes and communicates a wealth of information about the society in which it was created. "The African Presence in Mexico" at the African American Museum in Philadelphia is such an event.

This traveling show, organized by the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, is a hybrid. It uses art to reveal a relatively obscure - at least to Americans - aspect of Mexican cultural history. Yet it's clear that the art is being used as a means to an end rather than as the main attraction.

This is appropriate for the African American Museum, which regularly employs art this way. Only this time, instead of African American history, the subject is Afro-Mexican culture.

It might not have occurred to you that such a thing existed, yet black Africans have lived in Mexico since the advent of Spanish colonization in the 16th century. Their descendants live there still, concentrated in the southern part of the country, particularly around Veracruz on the Gulf coast and in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero on the Pacific coast.

The revelation that African blacks have contributed to Mexico's cultural history - something the Mexican government didn't formally acknowledge until 1992 - gives this exhibition its punch. The feeling of discovery is immediate; for American blacks and whites alike, Afro-Mexicanidad is a new world.

The Chicago Mexican museum organized the exhibition in the hope that exposure to Mexico's African connection would promote more amicable relations between African Americans and Latino immigrants, who both account for large segments of Chicago's population. As the exhibition makes clear, these groups share a lot of history, beginning with the fact that Africans were brought to both countries as slaves.

The show begins on this note, with a chart that traces the importation of Africans to Mexico between the late 16th and early 19th centuries. But then the emphasis shifts to works that memorialize a slave named Yanga, who in 1609 led a slave revolt and founded a city that was settled by his followers.

One of these works is a portrait of Yanga drawn on an ostrich egg by Fernando Vázquez Jácome; another, also by him, is a small carved wooden statuette. A painting by Hermenegildo González Fernández commemorates the founding of Yanga's city. These works all were made since 1984, indicating that the event still resonates intensely among Afro-Mexican artists.

Mexico's Africans effected sexual unions with the other two main ethnic groups, the Europeans (those born in Spain as well as in Mexico) and the various indigenous peoples. These relationships, as well as those involving Europeans and indigenes, were recorded in anonymous "caste paintings" that illustrated what the progeny of such couplings would look like.

The exhibition catalog describes the elaborate caste hierarchy developed by the Spanish overlords. Inevitably, Africans always found themselves near the bottom of the pecking order.

A large portion of the exhibition material consists of photographs, some historical but many more or less contemporary. It is mainly through these that one begins to recognize Mexico's African face. While the subjects are all Afro-Mexicans, it's not clear if the photographers are as well.

One noteworthy exception is Manuel Alvarez Bravo, perhaps the country's most famous 20th-century photographer, whose image of a seated female nude,

Black Mirror,

serves as the show's leitmotif.

Most of the photos are not so self-consciously arty. They're informal portraits of farmers, families, baseball players and housewives, all looking indubitably Mexican despite their African physiognomies. Among the photographers, Romualdo Garcia and Joaquin Santamaria offer impressive suites of images.

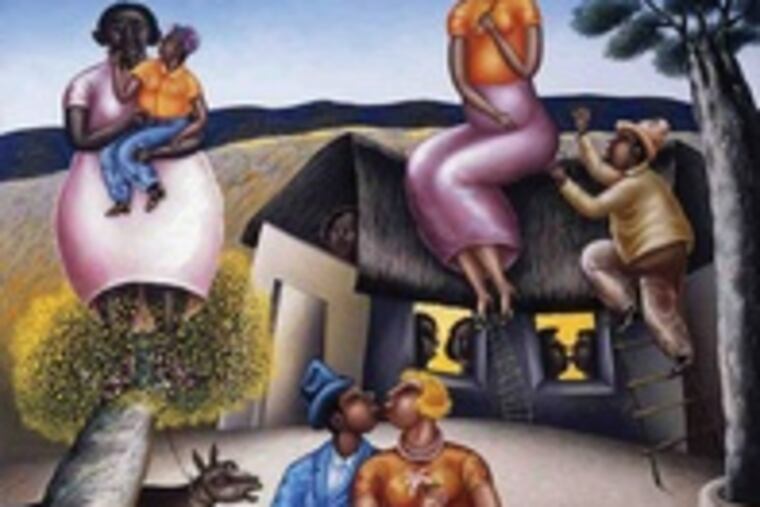

The show also contains a rich selection of paintings and prints, among which the colorful, folksy canvases of Aydeé Rodríguez López stand out. Look, too, for the vintage film posters and the costumes worn by dancers in the Veracruz Carnaval celebration, which display recognizable African qualities.

The exhibition, which comprises about 100 objects, is installed in two sections: an introductory historical survey and a more contemporary selection, "Who Are We Now?" It's here that one finds celebrated African American sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, who married Mexican artist Francisco Mora in 1947 and subsequently became a Mexican citizen. She's represented here by two prints and a small limestone sculpture of a woman titled

Shawl.

Compelling as it is, the show doesn't tell the full Afro-Mexican story, nor can it. For that, one needs to consult the catalog. Yet it's such a fresh and beguiling subject that one tends not to worry about the details. The main point - that Africans enriched Mexican history, and continue to do so - is hard to miss and gratefully received.

Video wall reconsidered.

Shortly after commenting on the spectacular video wall in the Comcast Center, it struck me that Liberty Property Trust, which owns the building and commissioned the display, could do something innovative with this technological marvel if it could handle a little risk.

Liberty could open the wall on a selective basis to established video artists of natural stature like Philadelphia's Peter Rose. In effect, the wall could be curated on an invitational basis, with the guest video pieces programmed, like art exhibitions, at specific times and dates.

Now the wall is running special programming developed by the Niles Creative Group of New York. This material is often clever, witty, technically dazzling and inspiring, but it is also uniformly anodyne. This is what one expects from a commercial venture, yet it seems something of a waste to use such an impressive instrument to present the equivalent of cutting-edge billboard advertising or television commercials.

Imagine what artists like Rose might do with a high-definition canvas of such imposing scale. Independent artists could transform the wall into a matchless performance venue, making Philadelphia a center for public video art.

Admittedly there's risk, but willingness to use the wall for art could only redound positively to Liberty and the building's main tenant, Comcast, which is, after all, in the television business. It could happen once the wall becomes a fixture. Let's hope it does.

Art: Africa in Mexico

"The African Presence in Mexico: From Yanga to the Present" continues at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, 701 Arch St., through Oct. 25. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays and noon to 5 p.m. Sundays. Admission is $8 general and $6 for seniors, students and children. Information. 215-574-0380 or

» READ MORE: www.aampmuseum.org

.