The grand old pipe organ of Ocean Grove

OCEAN GROVE, N.J. - For all their resemblance to majestic architectural edifices, pipe organs don't always reach their 100th birthdays with poise or pipes intact.

OCEAN GROVE, N.J. - For all their resemblance to majestic architectural edifices, pipe organs don't always reach their 100th birthdays with poise or pipes intact.

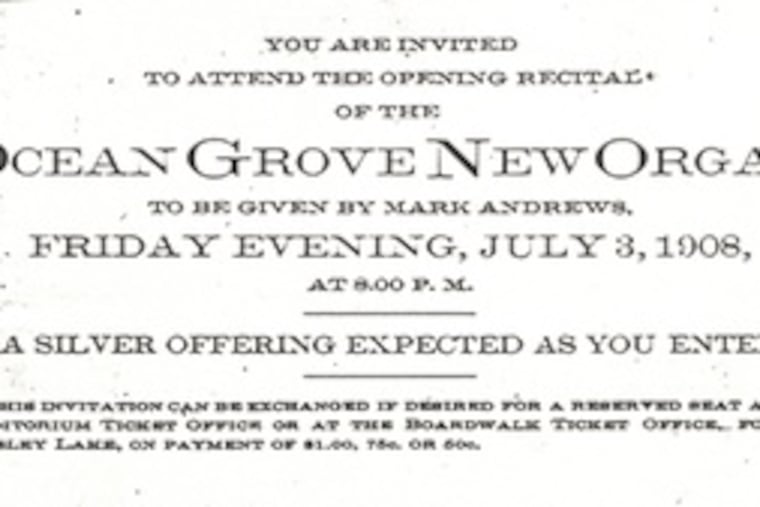

The Great Auditorium Organ here - an icon of post-Victorian culture in a Methodist-dominated village where time is held at bay - nearly didn't have a centennial worth celebrating this summer. But you wouldn't guess that from the way 300 to 400 people defer beachgoing until after July's noon Saturday recitals. The July 31 centennial concert isn't yet another organ workout, but a serious classical program featuring Philadelphia's Rittenhouse Orchestra.

"To me, the organ of Ocean Grove is the heart and soul of the community, both sacred and secular," says Michael Stairs, the Philadelphia Orchestra's organist and an annual guest at Ocean Grove, founded in 1872 as a Methodist camp-meeting site and now an interdenominational summer community nicknamed "God's square mile at the Jersey Shore."

"There's no greater thrill than hearing a distinguished preacher, and then having 4,000 people singing at the top of their lungs with the organ blazing," Stairs says. "That's something you don't often see anymore."

Heedlessly dispersed during a 1960s renovation, the organ's most towering and essential pipes were rediscovered in recent years - stashed in a garage or left broken in the auditorium basement - which allowed reassemblage of a sound admired by the great musicians who visited Ocean Grove early in the last century, from Ernestine Schumann-Heink to Enrico Caruso.

Such historic figures are still easy to envision in the leafy town square, which came by its gazebos honestly. Most sidewalks lead to the Great Auditorium, a sprawling wooden building almost the size of a football field with spirelike peaked roofs. Even that building needed its front extended to accommodate the organ's 1908 installation.

Inside, the seating capacity (ascetic wooden chairs) is an impressive 7,000 - after all, Billy Graham and Norman Vincent Peale have spoken there - under a ceiling edged with carousel lights. Illuminated religious declarations ("Holiness to the Lord," "So be ye holy") flank the organ, which is overtopped by a World War I-vintage American flag (a rigid panel, not cloth) frozen in mid-wave. It lights up, too.

The organ, which hibernates during winter when the auditorium is closed, has a high ratio of wooden (as opposed to metal) pipes, creating ethereal, mellow sounds with well-upholstered Victorian solidity.

"This instrument has a voice that's unique," says Gordon Turk, resident organist of 30 years, who has consulted on numerous organ renovations in the region. "I know it when I hear it, even a recording on the radio."

Says Stairs, "It's like comfort food."

Comfort, indeed. The words most often heard in association with the community's religious past are spiritual renewal as opposed to fire-and-brimstone conversion. In fact, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, whose philanthropy financed thousands of pipe-organ installations, arrived in Ocean Grove wanting an instrument "to overwhelm me with the feeling of how miserable a sinner I am," according to longtime curator John Shaw. Carnegie left Ocean Grove with his checkbook unopened.

Nonetheless, the fact that the organ has twice as many pipes (10,000-plus) as the town has people (4,200) suggests that the Great Auditorium got more than it bargained for. Organ builder Robert Hope-Jones was eager to create a demonstration instrument, and had his company put up half the construction money. "To build an immense organ for use only in the summer months - some individuals would say it's a bit over the edge," Shaw says.

Organs are often measured by their statistics. Philadelphia's Kimmel Center organ, designed partly as an ensemble instrument, has 125 ranks, or groups, that total 6,938 pipes. The Ocean Grove instrument, which serves a larger auditorium and more populist functions, and is more an orchestra unto itself, has 176 ranks totaling 10,823 pipes. The latest addition is an "echo division" that provides sonic reinforcement from the auditorium's rear.

However substantial, the organ now is about two-thirds of its original size, Turk says. The instrument became a bit of an orphan when Hope-Jones joined forces with the Wurlitzer company, fell out with its founding brothers, and ended his days, by his own hand, at a Rochester, N.Y., rooming house in 1914.

In fact, it fell into such disrepair that in 1961, the famous Virgil Fox played a concert at Ocean Grove and didn't mince words. "The organ was in deplorable condition," Shaw recalls. "Fox commented from the stage . . . he said if you'd driven a 1929 Ford across the country every year from 1929 to 1961, what would you need?"

A new one.

The renovation operated under the then-current old-is-bad, new-is-good mentality. "They thought the easiest replacement was the best way," Turk says. "They didn't want to rebuild the things that most demanded it. It was easier to replace with substitutes that were smaller, easier to work with, and more pliable."

The organ became an instrument more appropriate to a room with hundreds of seats, not thousands. One of the largest and most fundamental diapasons, or sets of pipes, was given away, Shaw says. "A guy had it in his garage for 25, 30 years and was going to install an organ in his house. He just happened to call me and said, 'I have these pipes.' "

The reconstruction began slowly when Turk arrived in the mid-1970s, often with parts from Philadelphia organs being dismantled, some with pipes dating to the 1880s. Slowly, the organ evolved from an instrument too infirm to convincingly render J.S. Bach to one of the more important instruments of its kind on the East Coast.

In a world of synthesized sound coming from software in increasingly tiny packages, the very idea of the pipe organ's massive hardware might seem utterly foreign to 21st-century sensibility. But not to Turk.

"The mechanics of the instrument - wind blowing through pipes - is like 10,000 people blowing on pipes on cue, with lung capacity coming from the basement," he said. "Were this a virtual organ or some kind of electronic reproduction . . . it wouldn't be the same thing."

As much as the organ appears to epitomize man-made music-making, the Ocean Grove instrument, as part of a nonwinterized building, can be seen as an organic part of the landscape that responds to temperature (which alters pitches slightly) and humidity.

"The more humid the atmospheric conditions, the more resonant the sound becomes," Turk says. "I guess part of that is because the sound is trapped. It's closer to the earth and doesn't escape as quickly as when it's dry and the air just seems to pull the sound away.

"I like it humid."

Listen to David Patrick Stearns and the Great Auditorium Organ on WRTI's "Creatively Speaking" at http://go.philly.com/stearnsonradioEndText

.