His best is missing in Ormandy CD retrospectives

Of all the great American orchestra builders of the mid-20th century, Eugene Ormandy most confounds rational reappraisal. That's partly because his vast discography generally has been marginalized in less-visible budget-line CD releases, and partly because the man whose Philadelphia Orchestra association spanned more than 44 years wasn't often heard in Europe. So while secondary conductors enjoy posthumous reputations thanks to live performances in German radio archives, Ormandy isn't much in evidence.

Of all the great American orchestra builders of the mid-20th century, Eugene Ormandy most confounds rational reappraisal. That's partly because his vast discography generally has been marginalized in less-visible budget-line CD releases, and partly because the man whose Philadelphia Orchestra association spanned more than 44 years wasn't often heard in Europe. So while secondary conductors enjoy posthumous reputations thanks to live performances in German radio archives, Ormandy isn't much in evidence.

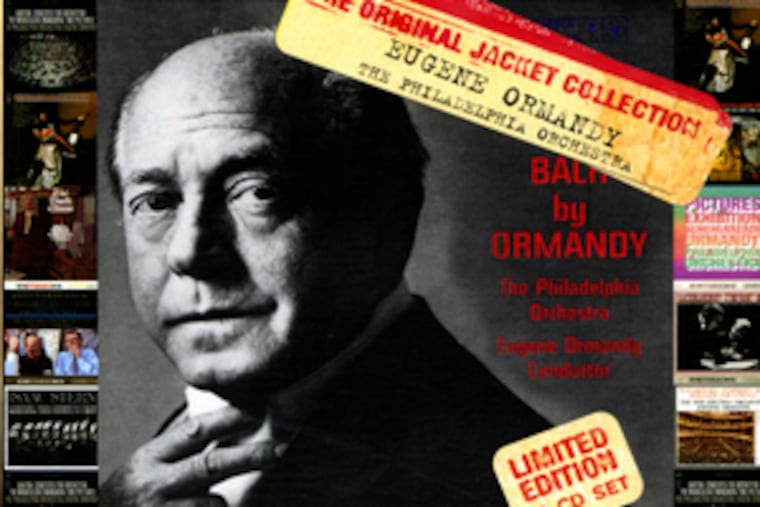

Only now has his primary recording label, Sony, given him a major retrospective: a 10-disc box in the label's Original Jacket Collection that features a cross section of Ormandy's stereo recordings in CD-size reproductions of their original jackets.

A few less-legitimate Ormandy collections have come out of Europe, drawing on recordings old enough to be out of copyright. The least haphazard of these is the 10-CD

Eugene Ormandy

on Membran, covering years between 1935 and 1949, which were somewhat immature, but feature notable collaborations with soloists such as Robert Casadesus, Emanuel Feuermann and Gregor Piatigorsky. Isolated DVDs are appearing, including a 1978

Scheherazade

at the Academy of Music that's just out on Medici Arts/Unitel Classics and, given its medium-warm level of inspiration, is of archival interest.

What's missing is the middle: Ormandy's best years, when he recorded less-characteristic repertoire, such as Haydn and Mozart, and did so extremely well, but in mono, which is of less interest to major labels, especially with an artist so identified with the famous Philadelphia sound - always best heard in stereo.

Because Ormandy cut such different profiles in each of his successive decades, it's hard to pin down how much he was operating from Old World training, on-the-job experience, and native instincts. No clues are to be had from Ormandy's rehearsal talk. Several Web sites feature Ormandy's fractured, self-contradictory commands.

"The notes are right, but if I listened, they would be wrong."

"I guess you thought I was conducting, but I wasn't."

"Who is sitting in that empty chair?"

Compared to his contemporaries Arturo Toscanini, George Szell and Fritz Reiner, Ormandy had the least-impressive resume, but the most lasting power.

Originally named Jenö Blau, a violinist trained in the great Hungarian tradition, he arrived in New York in the early 1920s, where he first played in the pit of the Capitol Theater. But he soon had a new profession (conducting light music) and a new name (taken from the ship that brought him to the United States, the Normandy). A mere decade later, he was music director of what is now the Minnesota Orchestra, and in 1936 he was brought to Philadelphia as a backup for Leopold Stokowski, who was increasingly consumed with battling the board and romancing Greta Garbo.

In contrast, Ormandy's relationship with the Philadelphia Orchestra board was such that he had an unofficial lifetime appointment. That proved troublesome when, before finally stepping down in 1980, he was physically compromised by age, and, it is said, several car-accident injuries. But in the best of times, he was so incapable of conducting complex meters that he had

The Rite of Spring

rewritten in 4/4 time.

Today, such limitations would have kept Ormandy from a major career. Even then, he clearly knew what was needed to keep him where he was. He instilled such fear that musicians adjusted to his idiosyncratic beat, as opposed to complaining about it. Of the Big Five Orchestra conductors, he was, by the mid-1970s, paid the least. He guest-conducted enough to flatter Philadelphia's civic pride, but covered his blind spots: His main Metropolitan Opera engagement was the lightweight

Die Fledermaus.

His ticket to security was the Philadelphia sound, and he maintained it above all else, even at the expense of more important musical values. One live recording with Beverly Sills singing Mozart's

Exultate, jubilate

has the Philadelphia sound sitting like irrelevant cake frosting on music that would be better off without it. Tempos and phrasing were strictly centrist. He may not have been a great conductor of music, it's often said, but he was a great conductor of musicians.

That translates into recordings that, at least in the stereo period of Ormandy's last 20 years, are comfortable, medium voltage, and not all that competitive in a crowded catalog of the kind of standard repertoire he did best. Many of his noblest efforts - Mahler's

Symphony No. 10

and Shostakovich's

Symphony No. 4

- were first recordings of problematic works that were destined to be (and were) superseded. Rather than playing to a particular strength, the Sony box is a cross section, and the glory that was Ormandy has its dubious moments.

Actually, some dubious hours are to be had in two discs of full-orchestra transcriptions of famous Bach tunes and organ works by Ormandy and others. Though the world is far more forgiving of any kind of transcription than it was 10 years ago, these aren't so much tasteless as cold and mechanical.

The Romantic Philadelphia Strings

disc is what was then called "easy listening," with the orchestra heard in echo chambers worthy of 101 Strings and seeking a middle ground between Arthur Fiedler and Mantovanni. Maybe that was commercially appealing 30 years ago, but not now. If there's a more legitimate show-off disc in the box, it's Respighi's Roman trilogy with the Philadelphians in knockout form.

The Russian works - Rachmaninoff's

Symphony No. 2

, Tchaikovsky's

Symphony No. 5

and Shostakovich's

Symphony No. 1

and

Cello Concerto No. 1

- represent the Ormandy/Philadelphia era at its peak. Though the world has become more accustomed to leaner, more nervous Rachmaninoff, the Tchaikovsky unfolds with Ormandy's own thrilling, cultivated, Old World "portamento" (a style of phrasing that died out after World War II).

There's an attractive steamroller quality to Bartok's

Concerto for Orchestra

- a kind of rhythmic deliberation that telegraphs the importance of the music - that also blunts the wilder

Miraculous Mandarin

. In the first of Rimsky-Korsakov's four movements in

Scheherazade

, the color just keeps piling on so thick that you wonder where the piece could possibly progress from there. Ormandy was not to be overestimated here; his secret was to just keep creating momentary sensation of one kind or another.

Many great conductors scoff at concerto accompaniments, but Ormandy loved them and is credited with telepathic talents in that regard. Maybe he made it too easy. In a disc of Tchaikovsky and Mendelssohn violin concertos, Isaac Stern is excellent, but doesn't rise to the level of fantasy and inspiration he delivered with conductors like Leonard Bernstein.

Ormandy's art, at least as documented here, was about comfortability over curiosity. And as nice as that is to encounter now and then, it's usually not quite good enough anymore.

Eugene Ormandy Boxed Sets

The Original Jacket Collection

(10 discs, Sony)

. Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy conducting. Music includes Respighi's

Pines of Rome

,

Fountains of Rome

and

Roman Festivals

; Mussorgsky's

Pictures at an Exhibition

; Rimsky-Korsakov's

Scheherazade

, Rachmaninoff's

Symphony No. 2

and

Vocalise

; Tchaikovsky's

Symphony No. 5

,

Serenade for Strings

and

Violin Concerto

(Isaac Stern, soloist); Bartok's

Concerto for Orchestra

,

The Miraculous Mandarin Suite

and

Two Pictures

; Mendelssohn's

Violin Concerto

(Stern soloist); Shostakovich's

Symphony No. 1

and

Cello Concerto No. 1

(Mstislav Rostropovich, soloist), various Bach transcriptions and waltz selections.

Eugene Ormandy (10 discs, Membran Music

).

Philadelphia Orchestra and Minnesota Orchestra, Ormandy conducting. Music includes Beethoven's

Piano Concertos Nos. 3

(Claudio Arrau, soloist) and

4

(Robert Casadesus piano); Mussorgsky's

Pictures at an Exhibiton

; Dvorak's

Cello Concerto

(Gregor Piatigorsky, soloist) Tchaikovsky's

Piano Concerto No. 1

(Oscar Levant, soloist) and

Symphony No. 6

; Brahms'

Double Concerto for Violin and Cello

(Jascha Heifetz and Emanuel Feuermann, soloists); Grieg's

Piano Concerto

(Artur Rubinstein, soloist) Rachmaninoff's

Piano Concertos Nos. 1

and

3

(Sergei Rachmaninoff, soloist); Strauss'

Don Quixote

(Feuermann, soloist) and

Sinfonia domestica

; Bruckner's

Symphony No. 7

;

Sibelius' Symphony No. 1

; Ravel's

Piano Concerto in G

(Casadesus, soloist); Mahler's

Symphony No. 2

;

Barber's

Essay No. 1

.