'Marley' led author to his new memoir

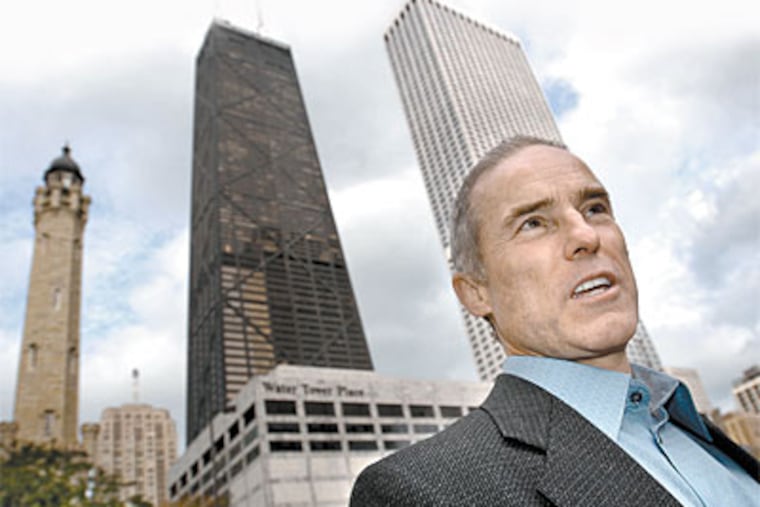

His dog has been very, very good to John Grogan. He's living a writer's dream: In a luxury suite on the 30th floor of Chicago's sparkly Ritz-Carlton, plush furnishings, room service scrambling with the wine, urban spires all but leaning through the windows, the former Inquirer columnist is relaxing, beer in hand.

CHICAGO - His dog has been very, very good to John Grogan.

He's living a writer's dream: In a luxury suite on the 30th floor of Chicago's sparkly Ritz-Carlton, plush furnishings, room service scrambling with the wine, urban spires all but leaning through the windows, the former Inquirer columnist is relaxing, beer in hand.

His 2005 memoir, Marley & Me, about life with his yellow Lab, Marley, has sold more than five million copies, and the movie opens Christmas Day, starring Owen Wilson as Grogan and Jennifer Aniston as his wife, Jenny (about which Jenny had few complaints).

There's Marley for adults, many kinds of Marley for kids (Marley: A Dog Like No Other; Bad Dog, Marley!; A Very Marley Christmas), not to mention dozens of non-Grogan Marley knockoffs in which people's lives are forever changed by their close relations with owls, cats, buffalo and parrots.

Now Grogan has written The Longest Trip Home (William Morrow, 352 pp., $25.95), a memoir of growing up in an Irish Catholic family, breaking away, and, through "gravitational pull," coming back full circle. Longest Trip, in effect, is the book Marley let him write. Both stemmed from a discovery Grogan made as a columnist: Readers crave personal connection.

Grogan is in Chicago as part of a book tour for Longest Trip that will take him on a long trip out West. Swinging east, it includes a stop at Philadelphia's Free Library on Dec. 18. Early reviews on the new memoir have been varied. Publishers Weekly found it "hilarious and touching," while the New York Times saw parts of it as "predictable" and "lightweight" while possessing "great charm." Such ups and downs are also part of the writer's life.

Longest Trip depicts Grogan's family, presided over by two devoutly religious parents, Richard and Ruth, in Orchard Lake, Mich., a suburb of Detroit. "My parents were convinced," he says, sitting in the hotel, "that the only true way to salvation was through the Catholic faith, and that their most important job in life was to raise their children in that faith."

But it was a faith that Grogan, the youngest of four children, grew away from: "I began to play it on both sides, living my own life but hedging on the truth" with his parents, "protecting them from this image of myself that wasn't what they wanted it to be."

Then Grogan met Jenny, a Presbyterian (he calls her "famously not Catholic"), "and it was she who said: 'What's going on here? You're 27 years old.' So I made the break."

Grogan, the father of three, says this story had been on his mind for years, and that "even as I was working on Marley, I was working on this, and I knew I would be mining that experience." What he lacked was a shaping, defining end that made it a true story.

That came with the illness of Grogan's father, a "diagnosis of leukemia that, despite the family's denial, wasn't going away." With his father's death in December 2004, and the rallying of the family to support their mother, Grogan saw the story's arc.

"If there's one underlying theme of the book," Grogan says, "it's that a family's love can trump, and triumph over, that family's differences, if you open your heart and laugh at them."

Where Marley "just spilled out of me," Grogan says, The Longest Trip was much harder work. Marley's 13 years on earth had a clear beginning, middle and end; Grogan's life as son and brother spanned 40 years. The challenge, as for any memoirist, was to "cull and shape those experiences that actually made a difference."

The story really is a circle, with a brother now living in the original family home back in Michigan, and Grogan's mother, 91, being cared for in the place the father intended.

"I talk in the book of telling my dad that 'we kids will keep the family together,' " Grogan says, "and indeed we are: We rally around our shared cause of keeping our mom happy and comfortable, and spending as much time as we can together."

Doesn't it take a lot of courage and/or hubris to write about your own experience? And how did a hard-news reporter discover he was made to write a memoir?

To the first question, Grogan answers, "Definitely yes. It's a leap of faith you need to make as a memoirist: That anyone's going to care." Life as a reporter had trained him not to make himself the point of his writing.

But then he became a columnist and discovered a funny thing.

"Reader response is like a perfect barometer: You file a column, and the next morning you look in your e-mail, and the inbox, it's either empty or it's full," Grogan says. "Some mornings I'd have seven e-mails, and I'd think, 'Oh, boy, I didn't hit it that time,' and other times there'd be 150 to 200 in there. And I started to see a correlation: The more I wrote about myself, the more people cared."

Not that Marley was born directly from his column. Grogan had long been telling tales of Marley at dinner parties, and "it was a scream, everybody would laugh - and then his reputation would start preceding me, and people would start approaching me and say, 'So what did he do this time?' "

Thus the book, and its undreamed-of success.

Contrary to popular belief, Marley was not what led Grogan away from newspapering. The success of Marley and its attendant obligations played some role, but it was Grogan's efforts to write Longest Trip while holding down his Inquirer column that proved too much, he says. So in February 2007, he decided to take a leave from daily journalism.

And now Marley has come to Hollywood, or is it the other way around? Seeing his book turned into a movie was both terrifying and satisfying.

"The Fox contract was fully two inches thick," Grogan says, "and they bought complete rights, meaning they could turn me into an arsonist if they wanted to, and make Marley a Chihuahua."

They didn't. But director David Frankel, he of The Devil Wears Prada, told Grogan that while liberties would be taken to make the story work on film, "we also want to be respectful of the story." Grogan hasn't seen more than a few "chunks of the film," but he says the liberties help tell the story: "The emotional truths and narrative arcs of our lives, I think, they accurately represented."

Told he looks nothing like Owen Wilson, Grogan laughs. "He'd be glad to hear it," he says. Wilson studied videos of Grogan, period photos, and family background, and when he arrived on set, "it was amazing how well he captured what was going on with me in 1993, down to the clothes he wore and a plastic Casio watch on his wrist."

Jenny, Grogan's wife, palled around with Aniston, even critiquing her makeup job, suggesting, "You've got to rough her up a little bit - she looks too good," Grogan says.

Wife and husband were extras in the film, some of which was filmed at The Inquirer.

Now a full-time book writer, Grogan misses the very thing that encouraged him to write about himself.

"I really miss Inquirer readers, who became friends and family to me," he says. "Every morning I'd pour coffee and log on to see what the Inquirer readers were telling me.

"It was a training ground for writing first-person nonfiction," Grogan says. It helped him create Longest Trip, as well as a book about a dog that "gave permission to a lot of people, especially guys, to feel grief." Firefighters, policemen, and other tough-guy types have told him they cried over Marley. More proof of the power of the personal.

"Heck," Grogan says, "I even got Howard Stern to cry. Not everyone can say that."

.