Art: When European prints went supersized

A painting nearly 12 feet high would be unusual, even today, but a woodcut on that scale, especially one created nearly 500 years ago, would be extraordinary.

A painting nearly 12 feet high would be unusual, even today, but a woodcut on that scale, especially one created nearly 500 years ago, would be extraordinary.

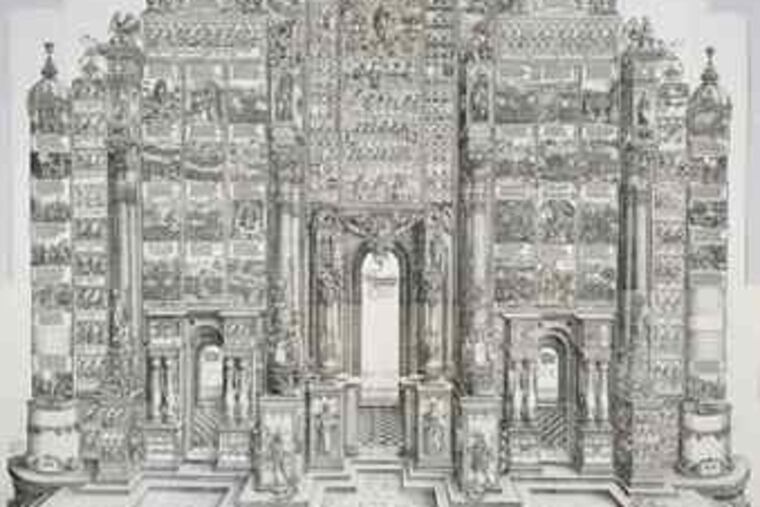

That's just one superlative that applies to The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I, the most remarkable object in an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art called "Grand Scale: Monumental Prints in the Age of Dürer and Titian."

In the early 16th century, no one could make a print that size from one block or engraving plate on a single sheet of paper. The original version of Maximilian's Arch was a composite that required 195 woodblocks. The version in the show, published in the 18th century, substitutes 18 etched sheets for missing blockprints.

Albrecht Dürer masterminded this awesome interpretation of a Roman triumphal arch, assisted by four other German artists and a host of carvers and printers. The print was commissioned in an edition of 700 by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, who distributed them around Europe as propaganda, to glorify his ascendancy over lesser rulers.

The Arch is mounted on the south wall of the museum auditorium because it's too large for the Berman-Stieglitz Galleries, where the rest of the 50 or so oversize prints hang. One doesn't need to be a prints connoisseur to appreciate how unusual and striking this collection is.

For one thing, most large-scale, multi-sheet prints, which proliferated during the Renaissance, haven't survived. Many were attached to walls and either wore out or were destroyed. Plates were lost, precluding the reproduction of complete images. And oversize prints were difficult to store in an age when most graphic images were book-sized.

One objective of this show, organized by the Davis Museum and Cultural Center at Wellesley College and guest-curated by University of Pennsylvania art historian Larry Silver, is to celebrate the survivors of the genre. Another is to demonstrate the imagination and technical virtuosity of the artists and craftsmen who collaborated on these prints.

For the purposes of this exhibition, a "monumental print" is defined as one whose subject - especially processions, city views, and multiple-character narratives - requires many sheets of paper, and a corresponding number of blocks or printing plates. The image is incomplete if any sheets are missing.

The Italian master Andrea Mantegna is believed to have ignited the vogue for composites in the late 15th century with engravings like Battle of the Sea Gods, one of the two earliest prints on view. At 11 by 31 inches, it's hardly "monumental" by modern standards, yet it surmounts the single-sheet limitation by extending over two sheets.

Maximilian's Arch, crammed with eye-straining detail and text, represents the other extreme; it's large enough to cover a wall and then some. The basic idea of this genre, though, is multiple plates or blocks, regardless of size.

Even the smaller prints are so dense with line, tone, and description that they require assiduous examination; one can't hope to get much out of a passing glance. So, even though 50 or so objects might not look like a major production, the show can occupy a visitor for some time.

If you choose not to pick out all the details or decipher the narratives, many based on mythology, religion, or history, you can't help but be impressed by the many examples of consistently brilliant technique. For instance, the modeling of figures in Jan Saenredam's eight-plate engraving The Punishment of Niobe is breathtaking. The multifigure frieze appears to be carved into the wall.

Many prints are woodcuts, which some people consider a relatively crude medium. You won't think so when you come upon a masterpiece such as Lucas Cranach's The Stag Hunt or Andrea Andreani's Sacrifice of Isaac.

To be sure, "Grand Scale" is a niche exhibition that will be most meaningful to, and enjoyed by, visitors with refined taste for graphic representation. Yet it's also a rare opportunity to enjoy an art form that rarely sees the light of day, even in museums with substantial print collections.

French art in Allentown. The Allentown Art Museum and the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis have devised a sensible way to combat the cost of organizing special exhibitions - they are exchanging collections. Allentown has lent 29 of its Italian, Dutch, and Flemish Old Master paintings to the Dixon, and has received in return 30 French works from impressionism to early modernism.

"Monet to Matisse" is a show of domestically scaled pictures that shares the large special-exhibition gallery with the museum's 30th juried show. It's a slightly incongruous juxtaposition that has been deftly executed to preclude a clash of sensibilities.

For anyone conversant with the principal impressionist and postimpressionist artists, the Dixon collection isn't a knockout. Rather, it's a representative survey that includes, besides the most prominent painters of the time, a number of lesser-known figures, such as Stanislas Lépine, Jean-Louis Forain, Jean-Francois Raffaelli, Eugène Isabey, Henri Rouart, Henri-Edmond Cross, and Maximilien Luce.

The character of this group of Dixon paintings strongly suggests that they initially were acquired by the institution's founders, Hugo and Margaret Dixon, for their home. Typically, such collectors can't always afford prime examples of the artists they admire.

A visitor to this exhibition should keep that in mind when noticing, for instance, that the Dixon's Renoir is a brushy, semi-abstracted seascape rather than a more typical figure.

Given those limitations, "Monet to Matisse" offers several dividends. One is the chance to see work by the aformentioned less prominent contemporaries of Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, and Alfred Sisley, all of whom are also included. The fellow-travelers are usually overshadowed or overlooked in painting shows from this period, but here they can be savored and appreciated.

While not all the Dixon pieces are standouts, especially the examples by the modernists - Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, and Chaim Soutine - the show contains some prizes.

Foremost among them are a luscious pastel of a dancer by Degas and a luminous landscape with figures by Paul Gauguin from his Pont-Aven period. Renoir's The Wave, a landscape by Camille Pissarro, and another by Pierre Bonnard also impress.

Art: Powerful Prints, Pretty Paintings

EndText