'To thee we sing': Historic Marian Anderson concert will be re-created in Washington, DC

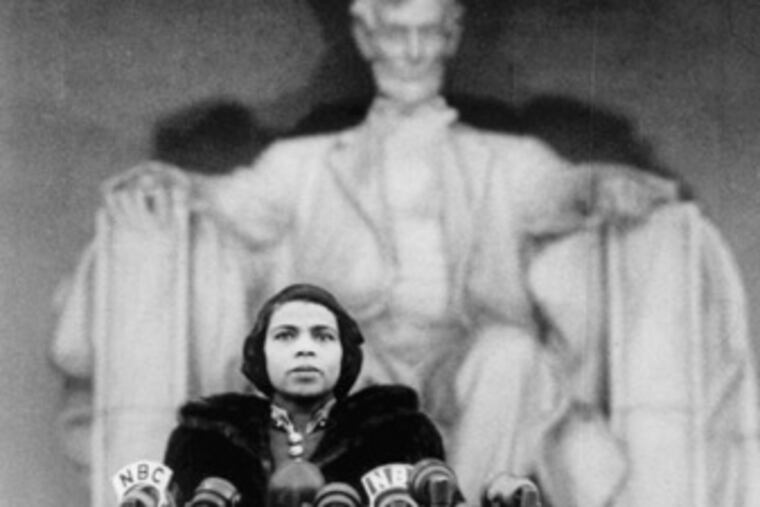

ON EASTER SUNDAY, April 9, 1939, Marian Anderson stepped up to a battery of microphones in front of Washington, D.C.'s, Lincoln Memorial, sang "America," and altered American history.

ON EASTER SUNDAY, April 9, 1939, Marian Anderson stepped up to a battery of microphones in front of Washington, D.C.'s, Lincoln Memorial, sang "America," and altered American history.

Wearing a mink coat and an orange-and-yellow scarf on that chilly afternoon, she changed the final phrase from "Of thee I sing" to "TO thee WE sing."

This modest African-American contralto had taken the train from her South Philadelphia rowhouse that day with her mother and sisters. Forbidden to stay at any Washington hotel due to segregation, they'd been promised lodging with former Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot.

The outdoor venue had been arranged by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, a Quaker, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow an African-American to sing in their Constitution Hall.

As a result, Roosevelt resigned from the organization, though political pressure kept her from attending the concert.

Anderson sang with her usual beauty, passion and tremendous dignity to a vast, racially integrated sea of 75,000 tearful faces on National Mall, as well as those listening on NBC radio. She performed a Donizetti aria that she had sung with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Schubert's "Ave Maria" and, after intermission, four spirituals.

The entire concert, attended by Supreme Court justices, legislators and more than 200 dignitaries, lasted less than an hour, but it has inspired generations.

Though Anderson never intended to be an activist, her concert was even more of a groundbreaking event for social consciousness and racial relations than the then-unimaginable reality of a black president and first lady in the White House.

At 3 p.m. on Easter Sunday, Washington-born mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves, a favorite of Philadelphia opera audiences, will step into Anderson's gigantic shoes to perform at the first concert symbolizing that 1939 affair.

The program, presented by the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, will also feature 55 members of the Chicago Children's Choir, the U.S. Marine Band and the a cappella group Sweet Honey in the Rock. Media arrangements were unconfirmed yesterday, but the event may be broadcast on C-SPAN and radio.

"Because of the 200th anniversary of the birth of Lincoln, there's something in the air regarding freedom and fresh meaning," said commission Executive Director Ellen Mackevich. "Marian Anderson spoke to us in the Depression, and there's a parallel now, especially with President Obama in the White House."

Graves is well aware of the symbolism of the upcoming event and her part in it.

"It's an awesome responsibility," Graves said recently, "although the commission's intention on honoring her legacy instead of focusing on a re-enactment takes a little of the heat from me!"

The concert

Graves will recreate the first half of Anderson's performance - "America," the Donizetti aria "O mio Fernando," and Schubert's "Ave Maria" - accompanied by pianist Warren Jones. And she'll do patriotic songs such as "America the Beautiful," as more than 500 people will go through a naturalization procedure during the event.

"One of the greatest thrills in my career was winning the 1991 Marian Anderson Award in Connecticut," Graves, who has sung here with the Opera Company of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Orchestra, recalled recently. "I had the opportunity to meet her and chat with her, and we attended a concert together at the Charles Ives Center. She never wanted to speak about the 1939 concert, having that quiet, modest elegance without any flamboyance, and not possessing the attitude we associate with performers today.

"It took great strain for her to trailblaze, but sometimes the gods draft the most unlikely. Someone had to be the first one, and I loved that it was Marian Anderson."

The lady from Philadelphia

Anderson was born in 1897 at 1833 Webster St. (now Marian Anderson Place), a modest home near 18th and Catharine streets. Her mother scrubbed floors at Wanamaker's department store, and her father sold ice and coal at the Reading Terminal.

She sang at Union Baptist Church but recalled being humiliated at being turned down by a local music school with the words, "We don't take colored."

The church supported her with handmade dresses and music lessons with local vocal coach Giuseppe Bochetti, who accepted her as his student after hearing her sing "Deep River."

Anderson attended William Penn High School, though, like other black students, she was not allowed to take academic subjects, then left before graduation to perform throughout the United States and Europe. She also sang locally and soloed with the Clef Club at the Academy of Music. She eventually returned to South Philadelphia High School for Girls, graduating in 1921 at age 24.

Signed by impresario Sol Hurok in 1934, she eventually would be booked in important venues throughout the world, always finishing her recitals of Brahms or Schubert or Schumann with her trademark spirituals to emphasize their validity.

In 1955, when she was well past her vocal prime, the Metropolitan Opera finally allowed her to sing her one stage role, the fortune teller Ulrica in Verdi's "A Masked Ball."

Her final tour, starting in 1964 at Constitution Hall and ending at Carnegie Hall in 1965, was a triumph.

After a 20-year courtship, Anderson married Orpheus "King" Fisher in 1943 and moved to Connecticut the next year. He died in 1986; they had no children. In 1992, she moved to Oregon to live with her nephew, conductor James DePreist. She died a year later.

In 2005, a ceremony celebrating a Marian Anderson 37-cent postage stamp was held in Constitution Hall, where the DAR offered an apology and reconciliation. The singer at that occasion was Graves.

Giving voice to others

The Marian Anderson Historical Society has been housed since 1997 in a modest house on South Martin Street below Fitzwater (now renamed Marian Anderson Way), where Anderson lived from 1924 until 1944, when she moved to Danbury, Conn. It's two blocks from her Webster Street birthplace. At the north end of the block is Union Baptist Church, which moved from 10th and Addison streets in 1915.

Last February, the Historical Society, a nonprofit organization that relies on donations, held its first annual vocal competition at the Franklin Institute, awarding three prizes, including one to local soprano Karen Slack.

(The annual Marian Anderson Award, given in Philadelphia to luminaries such as talk show host Oprah Winfrey; actors Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, and Richard Gere; musician Quincy Jones; and, this year, TV producer Norman Lear and writer Maya Angelou, is named after the singer but has no connection to the Marian Anderson Historical Society.)

Society caretaker Blanche Burton-Lyles has a very personal link to Anderson. Her mother was Anderson's piano accompanist at Union Baptist. Later, Anderson would have Burton-Lyles play while Anderson received guests at her home after concerts.

Anderson eventually recommended Burton-Lyles to Curtis Institute, where she studied with Isabel Vengerova and became the first African-American pianist to graduate and the first to play with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. (Burton-Lyles still plays Chopin and American popular songs at the Union League on Saturday evenings.)

Memorabilia of all kinds fill the Marian Anderson Residence/Museum, which receives more European than American guests.

There's an interactive video, Anderson's old birth certificate and scrapbooks with remarkable photos, including ones of Anderson singing with Leopold Stokowski and Leonard Bernstein, performing for Finnish composer Jan Sibelius and recording with Eugene Ormandy.

"Harry Belafonte and Gregory Peck came here when in town for the other award," said Burton-Lyles, "and Quincy Jones insisted on receiving his award at Union Baptist. Even when Marian became famous, she came back to church and sat in the balcony, always appreciating that they had paid for her lessons. Her final concert tour [in 1964-65] was actually sponsored by churches and sororities, especially the AKA [Alpha Kappa Alpha] that she belonged to.

"Several years ago, when I purchased her birthplace on Webster Street, I discovered at the settlement that the people who had lived in that house for 40 years had no idea that Marian Anderson had been born there."

There have been other Marian Anderson Awards. Anderson started her own competition in 1941 that honored young singers for many years.

In 1990, she began another competition whose first winner was the great operatic soprano Sylvia McNair, followed by Graves in 1991. Mount Airy native bass Eric Owens also was a winner. Since 2002, that award has been given biannually by the Fairfield County (Connecticut) Community Foundation jointly with the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

The Anderson legacy

Perhaps no one knows more about the impact of Anderson's 1939 concert than Raymond Arsenault, author of the just-published book "The Sound of Freedom: Marian Anderson, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Concert That Awakened America" (Bloomsbury Press, $25). Arsenault will discuss the book and Anderson's legacy at the Constitution Center tomorrow night.

"In 1939, Lincoln wasn't yet considered the great emancipator," explained Arsenault, "and the memorial wasn't sacred ground until then. Of course, Dr. King's 'I Have A Dream' speech was given there in 1963, and certainly that's why President Obama insisted on that location for his pre-inaugural concert. No one thought it unusual today that Aretha Franklin sang 'My Country, 'Tis Of Thee.'

"Anderson had faced all kinds of racism in the South. And singing at the Salzburg Festival in 1935, where Arturo Toscanini called hers 'a voice such as one only hears once in a hundred years,' the Nazis wouldn't even allow her name on the program. She wouldn't sing where blacks were segregated in balconies or back seats, but would allow what she called 'vertical integration,' where whites and blacks could sit on either side of the aisle."

Anderson almost canceled the Lincoln Memorial concert, never imagining she would become a civil rights icon. The concert made it evident that racial problems were of national consequence - not just a Southern problem but a stain on the national honor at a time when totalitarianism was sweeping through Europe.

"Anderson was . . . the first to enter into what was a white province - not jazz, blues, minstrelsy, vaudeville, or juke joints," said Arsenault. "Without her, we might not have heard of Leontyne Price, Jessye Norman or Denyce Graves. She confounded the stereotypes, beating them at their own game with poise, reserve and stature."

Anderson left an example of musical royalty, demonstrating the power of grace, determination and colorblindness. She once wrote:

"When I sing and see a mass of faces turned up to me, it never occurs to me that most of them are white. They are the faces of human beings. I try to look through their faces into their souls, and it is to their souls that I sing." *

Send e-mail to dinardt@phillynews.com.

NOTE: A previous version of this story had a headline indicating the re-creation would take place in Philadelphia. It is in Washington, D.C.