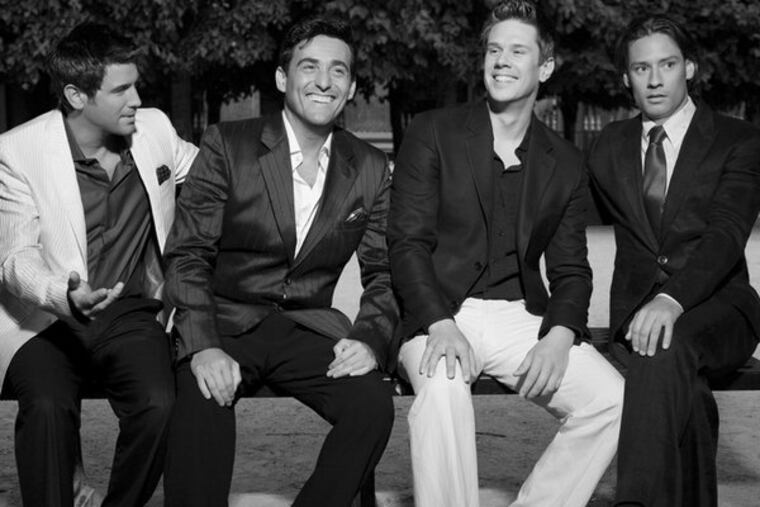

Four dashing men of international origin, sexy in their Armani suits, with voices bigger than the Grand Canyon, sing their hearts out on hits from Adagio in G minor to "Unbreak My Heart."

Four gorgeous British women wearing short red dresses and brandishing violins and violas release an album of classical faves and Led Zeppelin covers.

That's Il Divo - a creation of Simon Cowell of American Idol fame - and Escala.

But there's more.

Tenor Josh Groban just released a neoclassical version of the Broadway smash Chess. Britain's Got Talent winner Paul Potts is playing a casino in Atlantic City this summer. Rufus Wainwright makes his operatic compositional debut in England in a few weeks with Prima Donna.

A Philadelphia lyric soprano, Tonia Tecce, has released albums mixing Chopin's Etude in E minor with standards from Burt Bacharach and Hal David, while the Wilma Theater will be hosting The Rock Tenor, with Tran-Siberian Orchestra singer Rob Evan tackling Handel, Puccini, Daughtry, and the Police.

This is the thriving world of "popera" - the mingling of opera, pop, and standards - and its sister sound, classical "lite."

"I've not heard the term popera before, but it sounds like fun," says Tecce, who has performed the role of Marzelline in Fidelio with the Opera Company of Philadelphia. "If it gives an artist the opportunity to express himself or herself through a song, I am all for it."

The sound of popera grew over the last decade courtesy of Il Divo, Groban, and Andrea Bocelli, the Italian tenor whose lilting arrangements and creamy voice can render even the most traditional opera easy listening.

"It's an interesting phrase, popera," says David Miller with a laugh. He's an Oberlin Conservatory-trained tenor who was about to make his Metropolitan Opera debut in 2003 when he joined Il Divo. "It's such a bastard hybrid. . . . It's both opera and pop and neither."

It's also a blend that has found many detractors among opera lovers.

In 2008, soprano Kiri Te Kanawa told Britain's Telegraph newspaper that opera-lite crossover artists are "fake singers." The Times of London's Oliver Kamm famously wrote that "Opera with the excision of the drama of which the aria is an integral part is doubly diminished."

Responded Miller, sighing: "I guess we don't speak, necessarily, to pure opera fans. Then again, Il Divo's more accepted than groups like Amici Forever who directly take and change pieces from the classical repertoire - which, to purists, is sacred."

Still, to borrow from a famous album title by Elvis Presley - whose hit "It's Now or Never" was adapted from the opera classic "O Sole Mio" - 50 million popera fans can't be wrong.

Gary Bongiovanni, editor in chief of Pollstar, the magazine and Web site that track the concert business, points out that Il Divo and Groban have built their acts into worldwide attractions capable of filling sports arenas with people of all ages.

"Normally, such music's played in smaller performing arts centers to generally older crowds, but both relatively new acts have attracted a new and younger audience that's pushed them to larger venues," Bongiovanni said in an e-mail interview. "These artists are growing in popularity, which I interpret as a sign that the genre is growing."

In addition, Il Divo, Groban, and Bocelli have sold records that have gone gold (500,000 sold) and platinum (1 million).

"Purists might enjoy Il Divo, but it's not opera," Miller says. "Then again, there are Il Divo fans who will never love pure opera like they do us. What we're doing is not necessarily new because we're blending a bunch of old styles."

Before the recent growth in popera, there were theater singers like Andrew Lloyd Webber's ex-wife Sarah Brightman sweeping through classically imbued epics, and giants such as Luciano Pavarotti who recorded pop duets with Bono and Bon Jovi.

The popularity of classical lite can be traced, in part, to Walter Murphy's 1976 disco smash "A Fifth of Beethoven." But some of popera's roots were locally grown. South Philadelphia's Mario Lanza, whom Arturo Toscanini called the greatest voice of the 20th century, was a sensation in the true opera world (Madame Butterfly), Hollywood film (That Midnight Kiss, in 1949), and pop singles charts ("Be My Love" in 1951).

What does it mean to go from the grandeur of classical opera to something readily acceptable for all?

Tecce, who blends operatic songs with Hollywood and Broadway on her recently released Smile, studied voice with masters from the Juilliard School and the Metropolitan Opera. "I love the freedom of this music and the wonderfully truthful lyrics," she says of show tunes and classical songs.

Tecce doesn't try to make Broadway tunes and standards sound like opera, but sustains notes and produces pianissimo tones in a most dramatic way. "These things," she says, "give more emotion and feeling to the song."

Miller sees Il Divo's move toward pop tones as bringing the passion to their blend of operatic song. "My voice is about power and range. But in an acoustic environment like the operatic stage you can only drop down so far before people won't hear you. Putting amplification on my voice gives me an entirely other range for quiet intimate moments that a pop singer is naturally prepared for."

There's a formula to an Il Divo song, Miller says. It's not unlike riding a bike: The first gear is pop, the second is like the elevated chorus, the third and fourth gears are about adding power to the operatic core, and the fifth is where they let loose.

"That's what audiences respond to," Miller says.

Popera, then, is a mash-up of the techniques and style that form pop singing and operatic finale. "There's nothing else like what we do," he adds.

Though Il Divo isn't opera, Miller is proud of what he and his three mates do. Miller meets fans and reads on message boards that Il Divo has become the gateway drug for true opera.

"We make people opera-curious," Miller says, with a laugh.