Tracing a multiracial family history

While the folk song from which Danzy Senna's title is drawn - Black girl, black girl, don't you lie to me/Tell me where did you sleep last night - accuses a woman of promiscuity, her memoir is far more complicated: a compelling, often confusing foray into American family history.

A Personal History

By Danzy Senna

Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

200 pp. $25

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Helen Epstein

While the folk song from which Danzy Senna's title is drawn -

Black girl, black girl, don't you lie to me/Tell me where did you sleep last night

- accuses a woman of promiscuity, her memoir is far more complicated: a compelling, often confusing foray into American family history.

Senna writes from 21st-century Los Angeles, a place of "new money," "new races," and "perpetual amnesia" far away from her parents' "saga of the Deep South and the Deep North."

Unlike many people who flee west to forget a painful past, Senna - pregnant with her first child - wishes to examine it. She was born in 1970, in Boston, to a mother whose history was "woven into the myth of the city itself," and to a father she describes as "a Negro of exceptional promise" raised in a housing project.

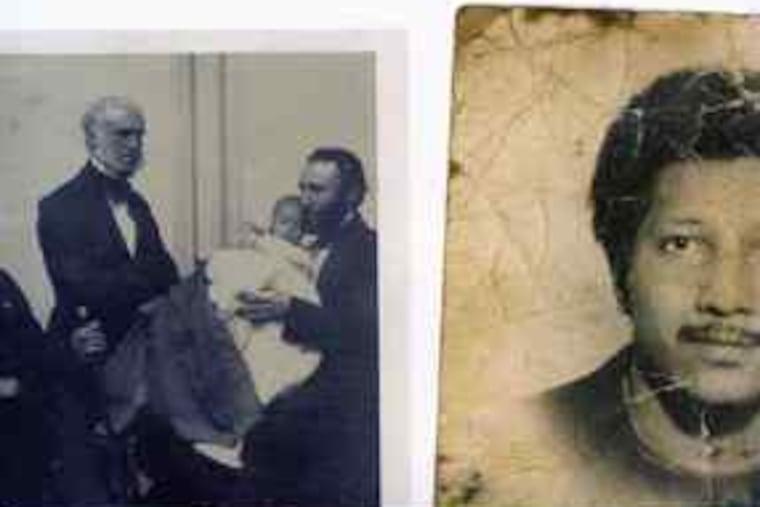

Her mother's white ancestors are extensively documented back to the Mayflower. Her father's black ancestors lack any documentation. His father is said to have been a Mexican boxer; his mother, a shy, musically gifted teacher who died of cancer when Danzy was 2.

This split in Senna's family history; the ways race, racism, poverty, place, and class shape it; and the insidious and lasting effects of childhood trauma are all themes that pull the narrative in many different directions. But the strongest current, a persistent undertow, is Senna's quest to understand her parents, especially her father.

Carl Senna, as his daughter describes him with devastating clarity, was a black intellectual who had lost everything that mattered to him by the time he was 30. "Gone was the 'Negro of exceptional promise,' and in its stead he lived up to all the stereotypes that his fellow Americans had ever secretly or not-so-secretly harbored about black men. He could not consistently stay sober. He got fired from his job. And, after my mother left him, he followed her one night to a friend's dinner party and in front of all the guests dragged her down the steps by her hair and beat her in the street."

Fanny Howe was then a young writer and college dropout from an eminent family that included liberal academics, a bishop, and a slave trader in its tree. The couple married in 1968, the year when the last of American miscegenation laws was finally revoked, at a crossroads in American history.

In 1975, when the author was 5, Howe obtained a restraining order against Senna, packed up, and fled. Like many children of divorce, their three children became pawns in their parents' ongoing battles. But, in addition, parental psychology and Boston's culture conspired to leave no part of their lives untouched by consciousness of race.

Although Danzy looked Caucasian, she recalls: "My father constructed for himself - and imposed on us - a blackness that was intellectual and defensive, abstract and negatively defined (always in relation to whiteness). And it worked: My siblings and I never once felt ourselves to be anything but black."

This shocking and multilayered beginning, narrated with authority by an author who has mined some of this material in her novels Caucasia and Symptomatic, segues into a father-daughter road trip in search of family roots. Danzy flies her father, with whom she has a difficult and ambivalent relationship, from Canada to Louisiana, where Carl Senna was born in 1944. The plan is for him to introduce his daughter to his childhood world.

Among the few documents she has located is a file from the Bureau of Catholic Charities describing an Alabama orphanage "for poor unfortunate colored boys and girls between the ages of three and sixteen," where Carl was left by his mother at the age of 5. He blames his own violence on the abuse he suffered there at the hands of the nuns. But in one of the many things left unexplained in this memoir, Carl flies home before attempting to visit the place.

Driving her rented SUV into Alabama alone, walking into churches and kitchens, Danzy encounters a series of people who feel like extended family even when their relationship to her is unclear. Ernestine Hurston, another orphan from Zimmer Home who has been waiting for Carl Senna to turn up for decades; Betty Jean Foy, Yvonne and Dessie - who fill in the blanks about her mystery-shrouded grandmother and her decades-long affair with a Father Francis Ryan, whom she followed from Alabama to Boston.

Then we are back in California, with Senna reworking the story of her parents' relationship in light of what she has learned in the South. She rereads accounts of her mother's family members in a public library, resifts memories of her father, and then launches into an introduction of Carla, Carl Senna's sister or maybe half-sister, whom she discovers via an e-mail from a professional genealogist.

There are so many characters, places, and names in this jam-packed book that even Tolstoy would have had a problem managing them. Senna tries to do it in 200 pages, and her point of view, so precise and insightful at the outset of her quest, becomes muddled by the end.

The challenge of writing a family history as the multiracial child of a bitter divorce in America is enormous, and many parts of the story are still too explosive for her to recollect in tranquillity. She's wary of slipping into the role of "tragic mulatto" while struggling to get a dispassionate handle on her father, his mother, her mother, the pervasive racism and failures of personal responsibility in her story.

I found parts of this memoir brilliant, but wondered why Senna often accepted what people told her at face value and backed off from cross-checking and more contextual research. Was it too painful, too taxing, or just uninteresting?

Where Did You Sleep Last Night? takes us into very complicated sociological and psychological territory; Senna's memoir needed more work to fully realize its ambitious agenda.